- Japan’s new subsidy plan: Tokyo is preparing to subsidize telecom giant NEC’s purchase of its own ocean-going undersea cable-laying ships, covering up to half of the roughly $300 million price tag per vessel Tomshardware Lightreading. This marks a strategic shift as NEC – one of the world’s top undersea cable installers – currently owns no cable ships and has relied on leasing foreign vessels Tomshardware 1 .

- National security at stake: Japanese officials warn that relying on rented ships for critical internet infrastructure is a “very serious” vulnerability Tomshardware. The government now views the lack of domestic cable-laying capacity as a national security risk that could slow emergency repairs and expose Japan’s data links to adversaries Tomshardware Asahi. “It would be a big disaster if Japan’s subsea cables were severed by a country of concern and the internet were shut down,” cautioned Japan’s economic security minister Sanae Takaichi 2 .

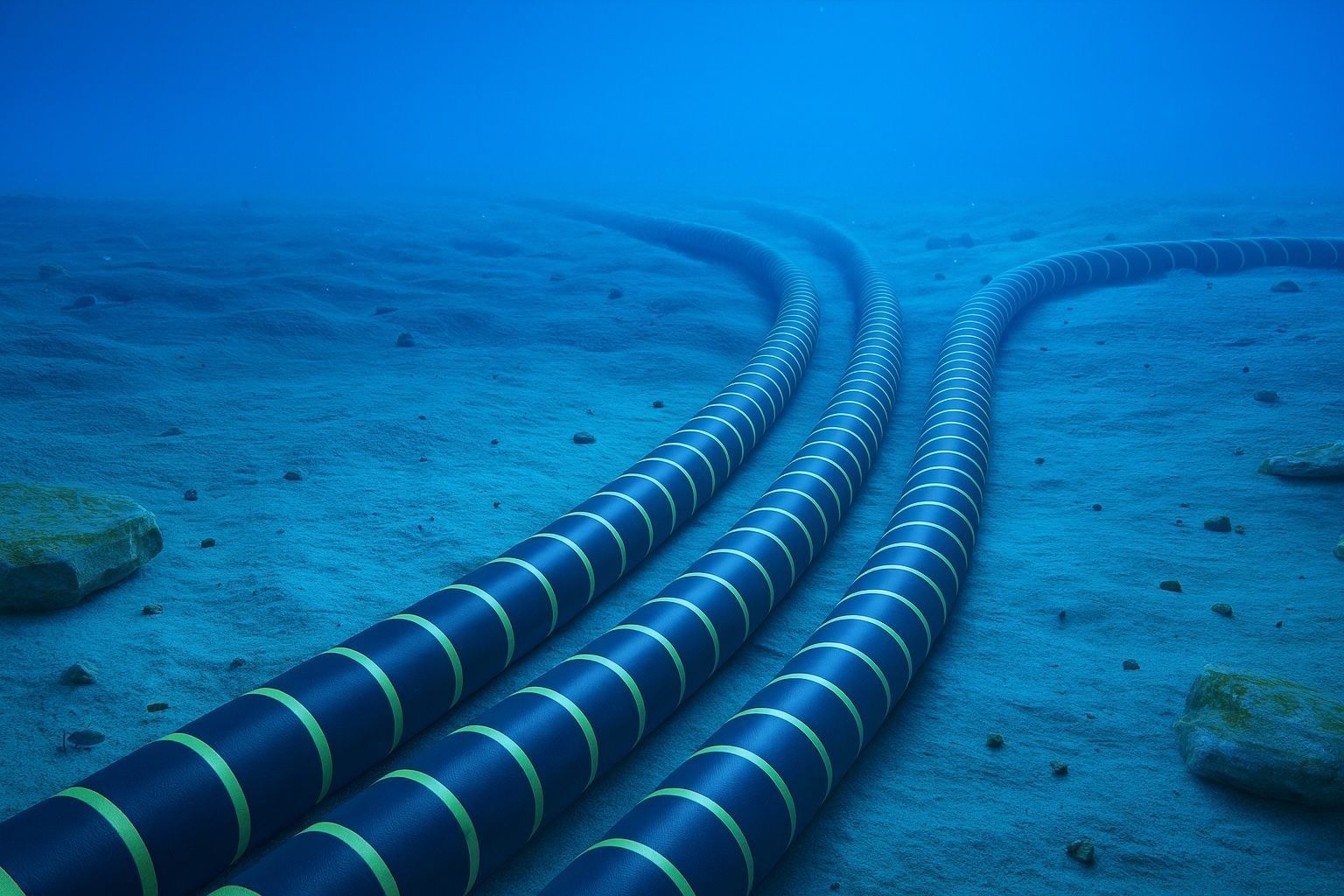

- Undersea cables carry 99% of data: Nearly all international communications – from social media and finance to military orders – ride through some 450 undersea fiber-optic cables stretching ~1.4 million km across oceans Asahi. Governments increasingly recognize these cables as critical infrastructure, since a single break can disrupt entire countries. The U.S. government, for example, has broad security concerns about the 400+ subsea cables that handle “99% of international internet traffic” 3 .

- Wave of sabotage and outages: Recent incidents underscore the threat. In 2023, Taiwan accused Chinese vessels of deliberately cutting the only two cables to its Matsu islands, severing internet access Reuters. Mysterious cuts to Nordic cables in the Baltic Sea triggered sabotage investigations Reuters. A Chinese freighter was suspected of damaging a U.S.-Taiwan undersea link in early 2025 Tomshardware, and ships of murky origin have repeatedly “accidentally” severed cables from Finland to Estonia and elsewhere Tomshardware. Even civil conflicts have spilled into the ocean: Houthi militants in the Red Sea were blamed for cutting three major cables carrying data between Europe, the Mideast, and Asia Reuters. The vulnerability is clear – cables lie in international waters, often unprotected, so attackers can operate with deniability by claiming it was an accident 4 .

- Global scramble to secure cables: Around the world, democracies are racing to shore up their undersea cable defenses. The United States is moving to ban Chinese components from undersea cables that land on U.S. shores, to guard against espionage and sabotage Reuters Reuters. France announced plans to nationalize Alcatel Submarine Networks, its leading cable firm, to protect it Asahi. India is readying investments in cable maintenance ships – including buying new locally built vessels and converting navy ships – after U.S.-India talks highlighted the need for “trusted” partners instead of Chinese vendors Lightreading Lightreading. Even smaller nations like Taiwan have begun coast guard patrols around their undersea cable routes for protection 5 .

- Data boom meets aging fleet: A looming capacity crunch adds urgency. Nearly 47% of the world’s cable-laying and repair ships will retire in the next 15 years, even as demand for new cables explodes Lightreading. Industry experts forecast 1.6 million km of new submarine cables will be needed in that period – roughly double the amount being phased out Lightreading – driven by surging internet usage and data-intensive applications like cloud services and AI. SubCom (U.S.), ASN (France), and HMN Tech (China) each maintain fleets of specialized cable ships, but NEC until now had to charter vessels ad hoc Tomshardware Tomshardware. The Japanese government’s subsidy aims to close that gap, though building a new cable ship can take 2–3 years, meaning NEC’s first owned vessel might not launch until 2027 6 .

Japan’s Bold Move: Subsidizing Cable-Laying Ships

Japan’s decision to bankroll NEC’s purchase of undersea cable vessels signals a major policy shift to protect the nation’s digital lifelines. According to officials, Tokyo is prepared to front hundreds of millions of dollars so that NEC – Asia’s biggest undersea cable installer – can acquire ocean-going cable-laying ships of its own Tomshardware Lightreading. Each such ship is a massive specialized vessel (costing about $300 million apiece) equipped to carry and slowly spool out thousands of kilometers of fiber-optic cable across ocean floors. Until now, NEC has owned zero of these, relying instead on leasing a Norwegian ship (whose charter ends next year) and renting smaller domestic vessels for regional projects Tomshardware. This made Japan an outlier; its rivals SubCom (USA), Alcatel Submarine Networks (France), and HMN Tech (China) each operate fleets of 2–7 cable ships to swiftly serve their needs Tomshardware 7 .

Japanese leaders now consider it untenable for a country of Japan’s size – which depends on subsea cables for 99% of its communications Csis – to lack sovereign capability to lay and repair those cables. Government officials told the Financial Times that NEC’s dependence on foreign-owned ships is a strategic weak point: if a cable fails or needs urgent installation, Japan could be stuck waiting in line for a leased vessel Tomshardware. “The Japanese government thinks this situation is very serious, so we are thinking we need to make some intervention,” one official said Tomshardware. In late 2023, Japan had already taken initial steps by officially designating subsea cables as “vital infrastructure” – requiring operators to report any suspicious incidents – and by funding studies on how to assist Japanese companies in owning cable ships Asahi Asahi. But until now, action was limited. NEC’s CEO lamented earlier this year that “we are the only one fighting with no support” while competitors enjoyed government backing Asahi. Indeed, France moved to nationalize its Alcatel cable unit in 2023 Asahi, and China heavily subsidizes its state-owned telecom firms Asahi – leaving Japan’s industry essentially fending for itself 8 .

That era appears to be ending. By offering to split the cost of new ships 50/50 with NEC, Japan would effectively invest on the order of $500 million (if two vessels are acquired) to ensure one of its most important tech companies has “unfettered access” to its own cable fleet Tomshardware Tomshardware. The first Japanese-owned transoceanic cable ship is tentatively expected by 2027, pending final approvals Lightreading. Once in service, these vessels would give NEC (and by extension, Japan) far greater autonomy and quick-response capability for undersea cable projects – whether laying new routes to allies or repairing damaged lines in an emergency.

NEC’s leadership acknowledges both the benefits and risks of owning cable ships. Takahisa Ohta, senior director in NEC’s submarine network division, noted that maintaining a vessel is a “huge fixed cost” – a burden if the market slumps – but he also conceded that with today’s booming demand, “one option is to acquire our own ship, and it’s something we’re considering.” Tomshardware In other words, the government’s support may tip the balance to make this long-term investment worthwhile. It comes as global demand for new cables is surging (driven by cloud computing, 5G, and data-hungry AI applications) – a trend that has made the undersea cable business “boom” in recent years Tomshardware. Tokyo’s gambit is that by bolstering NEC now, Japan will secure its place in the forefront of that industry and safeguard its communications in a crisis.

Why Undersea Cables Are a Security Concern

Undersea fiber-optic cables form the backbone of the modern internet – yet they’re frighteningly vulnerable. These bundles of glass strands, no thicker than a garden hose, lie mostly unguarded on seabeds, carrying everything from YouTube videos to bank transactions and military communications. If severed or tampered with, data flow can halt in an instant. Unlike a land-based outage, fixing a subsea cable isn’t as simple as sending a crew to a cell tower; it requires dispatching one of the limited cable ships to haul up the broken line from depths that can reach 5,000 meters, then splicing it – a process that can take days or weeks for a single break.

For decades, this fragility was an overlooked risk. But a series of incidents and growing geopolitical tensions have turned undersea cables into a national security priority for many countries. Military and intelligence officials warn that hostile nations or non-state actors could target cables in a conflict or as a form of coercion – and do so covertly. Because cables in international waters fall outside any one nation’s jurisdiction, an attacker can claim plausible deniability (e.g. blaming a wayward ship’s anchor or natural event) Tomshardware. Importantly, such sabotage doesn’t automatically trigger a military response, since it occurs in a gray zone below the threshold of an obvious armed attack Tomshardware. This makes cable-cutting a tantalizing asymmetric tactic.

Recent events have proven that this is not just theoretical:

- Nordic outages: In late 2024, undersea data cables connecting Finland with neighboring Sweden and Estonia were mysteriously severed in separate incidents Tomshardware. These cuts – coming on the heels of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – immediately raised suspicions of Russian sabotage, though definitive attribution proved difficult. Finland’s government noted the timing was “no coincidence” as the damage occurred amid heightened tensions in the Baltic region.

- Taiwan and Chinese “fishing” vessels: In early 2023, Taiwan’s outlying Matsu Islands lost internet access after both of their subsea cables to the main island were cut. Taiwanese officials accused two Chinese ships – ostensibly fishing boats – of intentionally damaging the cables Reuters. The incident left the islands largely offline for weeks, underscoring how easily critical infrastructure could be disrupted under the cover of routine maritime activity. Then in 2025, a Chinese commercial freighter was charged by Taiwan for allegedly snagging and breaking a major cable linking Taiwan to the United States Tomshardware Csis. The following month another ship was suspected of cutting a second cable – a one-two punch that prompted Taiwan’s Coast Guard to begin escorting cable repair ships and patrolling its undersea cable routes as a protective measure 5 .

- Conflict zones (Red Sea and beyond): During Yemen’s civil war, Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea in 2022 were blamed for cutting three international cables that route internet traffic between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia Reuters. The resulting outages slowed internet speeds for millions of users in Africa and the Gulf. Similarly, in the Mediterranean, reports emerged of undersea cables mysteriously cut near conflict zones, suggesting state or proxy actors testing sabotage tactics.

- Shadowy vessels in Europe: Western countries have grown alarmed by unusual activities of ships near their critical cables. In one case, the crew of a Russian “ghost fleet” tanker was charged with intentionally damaging cables off the coast of Ireland – allegedly as part of Russia’s espionage or sabotage operations Tomshardware Tomshardware. NATO navies have increased patrols and even stood up special units to monitor undersea infrastructure in response to such threats.

These episodes highlight how something as mundane as a ship dragging an anchor can in fact be a calculated attack on infrastructure. Intelligence analysts describe undersea cables as the soft underbelly of global connectivity – easy to hit, hard to defend. As U.S. FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr put it in July 2025, “We have seen submarine cable infrastructure threatened in recent years by foreign adversaries, like China.” Reuters He noted that protecting these cables against “cyber and physical threats” is now a core security mission 9 .

Crucially, cable vulnerabilities extend beyond sabotage. Espionage is another worry – adversaries might tap cables to intercept data. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union famously tried undersea cable espionage. Today, the fear is that companies with ties to hostile governments could embed backdoors or surveillance tech in the cables’ landing stations or repeaters. This is why the U.S. and its allies are barring “untrusted vendors” (meaning Chinese telecom giants like Huawei and ZTE) from supplying undersea cable systems Reuters. Since 2020, U.S. regulators have blocked at least four planned cables between the U.S. and Hong Kong due to espionage concerns Reuters. In the same vein, the FCC in 2025 proposed new rules to prohibit any Chinese-made equipment in the network of undersea cables connecting to America Reuters. The goal is to ensure that everything from the fiber and repeaters to the landing station routers are from “trusted” sources, closing any backdoor for data theft 10 .

Japan faces both these challenges – physical threats to its cables, and the strategic risk of Chinese influence in cable networks. As an island nation, Japan is especially dependent on subsea cables (virtually all its external data flows through them) Csis. Government studies have mapped how Japan’s international cables mostly come ashore in just two areas – off Chiba near Tokyo, and off Shima in Mie Prefecture – making an attractive target for disruption if an enemy cut a few key points Asahi. This realization, along with stories of exposed cables visible in shallow Okinawan waters Asahi, spurred Japanese lawmakers to act. When a senior lawmaker publicly warns that a rival power could “shut down the internet” by cutting Japan’s cables Asahi, it resonates as a clear call to bolster defenses.

The Global Race for Control of Undersea Networks

Protecting undersea cables isn’t just a national security issue – it’s also a geopolitical and economic competition. Control over the world’s data pathways equates to strategic leverage. This fact isn’t lost on the great powers: just as Britain once dominated undersea telegraph lines in the 19th century to further its empire, the U.S. and China today are vying for influence over the fiber-optic webs that bind continents Asahi 11 .

China’s expansion in the subsea cable arena has especially rattled other nations. A Huawei-affiliated firm (now rebranded as HMN Tech) has rapidly grown its share of the market, often undercutting Western competitors on price. Beijing has folded undersea cables into its Belt and Road Initiative, aiming to build a globe-spanning network of Chinese-made fiber routes linking Asia, Africa, and beyond Asahi. Along with the cables, China often offers to build the landing stations and provide the internet equipment (even smartphones and apps) in recipient countries Asahi – a full package that can increase those nations’ reliance on Chinese technology. Western officials fear this could enable Chinese surveillance or give Beijing a chokehold on other countries’ communications 12 .

In response, the United States launched the “Clean Network” program in 2020 to exclude Chinese vendors from telecommunications infrastructure, including undersea cables Asahi. U.S. security agencies have leaned on tech companies and foreign partners to avoid Chinese cable projects that could compromise data. A notable example was the scuttling of a Facebook/Google-backed undersea cable from California to Hong Kong in 2020 due to U.S. government pressure, citing the risk of Chinese spying Asahi. Washington instead has promoted alternate routes that bypass Chinese territory – for instance, supporting new cables from the U.S. to Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia that utilize “trusted” suppliers.

Allied coordination to counter China’s cable influence has also ramped up. In the Pacific, the U.S., Japan, and Australia jointly funded an undersea cable to the small island nation of Palau after the contract was pulled from a Chinese bidder Asahi. Similar collaborative projects are extending high-speed links to Micronesia and other Pacific islands to block China from dominating local connectivity Asahi. These moves are about more than better internet – they prevent a scenario where Beijing could potentially cut off or monitor entire countries’ communications at will.

Japan, for its part, has been cast as a pivotal “trusted vendor” in this contest. When U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken made an unusual visit to NEC’s Tokyo headquarters in mid-2023, it sent a strong signal Asahi. Blinken toured NEC’s cable manufacturing exhibit under heavy security and later praised the company as a “trusted vendor” Asahi – implicit code for “unlike those Chinese companies we distrust.” This U.S. endorsement of Japan’s cable industry highlights how allies are closing ranks to secure supply chains. In fact, Japan’s government and industry have grown increasingly wary of any dependence on China for undersea cable projects. There is concern that Chinese cable-laying ships operating near Japan – even ostensibly for cooperative projects – could covertly map Japan’s seabed or critical infrastructure, knowledge that might aid Chinese naval operations Asahi Asahi. Such fears have strained what used to be a pragmatic arrangement where Japanese, South Korean, and Chinese firms sometimes shared cable-laying vessels for cost efficiency Asahi. Now, security trumps cost: Japan would rather pay more or delay a project than invite a Chinese “partner” ship to its waters.

We are seeing analogous calculations elsewhere. India, which lies along key Indian Ocean cable routes, has also kept a wary eye on Chinese involvement. After high-level talks with the U.S., India stated it will use “trusted vendors” for maintaining cables in its waters Lightreading – a clear signal to keep Chinese firms out. New Delhi is reportedly ready to spend ₹30–40 billion (up to $450 million) to build its own cable repair ships domestically Lightreading. Additionally, India’s Navy is considering retrofitting older naval vessels for cable maintenance duties Lightreading. These steps are meant to cut down repair times (currently a critical cable break could take two weeks to fix, by one estimate) and to ensure India isn’t reliant on foreign entities – especially not Chinese – to restore its internet links Lightreading 13 .

Meanwhile, Europe has taken measures to secure cables as well. The European Union has held exercises simulating cable sabotage and is setting up a new undersea infrastructure coordination cell at NATO. The United Kingdom announced it is deploying specialized naval ships to guard undersea cables and pipelines in the North Atlantic, given concerns about Russian submarines prowling near vital lines. And as noted, France doubled-down on its strategic cable asset, ASN, by bringing it under full state ownership in 2023 Asahi to prevent any foreign takeover and to invest in expanding its fleet.

In short, ensuring control and protection of undersea cable networks has become a collective priority for like-minded nations. Japan’s latest move to subsidize cable ships fits this pattern: it’s about bolstering one of the “friendly” pillars of the global internet against potential choke points or meddling by adversaries. Each new secure cable route laid by trusted firms, and each new cable ship added to allied fleets, is seen as one more safeguard for the free flow of data.

Challenges Ahead: Costs, Capacity, and Cooperation

While governments are now keenly interested in undersea cables, addressing the challenges won’t be cheap or easy. One immediate hurdle is financial: these cable-laying vessels and the operations around them cost a fortune. A $300 million ship is just the start – crews, maintenance, fuel, and port infrastructure add ongoing expenses. Industry veterans remember the early 2000s telecom bust, when over-investment in fiber (both terrestrial and subsea) led to a glut of capacity and idle ships. NEC’s own submarine cable director warned that if the market downturns, owning such a vessel could become “simply a big cost” with little return Tomshardware. In other words, today’s boom could be tomorrow’s oversupply. Governments subsidizing the purchases may lessen the upfront burden, but companies like NEC will still shoulder operating costs long-term. They’ll need enough consistent cable projects – and paying customers (like Big Tech firms or consortia that fund new cables) – to keep those ships busy.

Another looming problem is a potential shortage of skilled manpower and manufacturing capacity. Undersea cable work is highly specialized. There are only so many engineers who know how to design cable routes, ship crews trained in delicate deep-sea cable repair, or factories (like NEC’s OCC subsidiary in Japan) that can produce thousands of kilometers of fiber that can survive extreme ocean pressure Asahi Asahi. Scaling all this up takes time. The cable industry, somewhat ironically, hasn’t benefited much from automation – making and spooling subsea cable is still labor-intensive, almost hand-crafted work Asahi Asahi. As the OCC plant experience shows, attempts to automate the process have failed so far, meaning human expertise remains crucial Asahi. Training new specialists and ship crews is as important as building the ships themselves.

Furthermore, even as new players like NEC (with its future ships) and India enter the fray, the global demand may outpace supply for some time. The SubOptic Association (an industry body) has warned that nearly half of all cable-laying and repair vessels worldwide are set to retire by 2040 Lightreading. Many of those ships date to the 1980s and 90s cable boom and are nearing end-of-life. Replacing them is no small task – it’s not just Japan that needs new ships, it’s everyone. Yet, building new vessels at the needed rate will require coordination among governments, industry, and possibly navies (as interim solutions). The SubOptic report projected roughly 1.6 million kilometers of new cables will be laid in the next 15 years – about twice the amount of old cable being decommissioned Lightreading. This implies a breakneck pace of deployment to connect new data centers, 5G networks, and remote regions. If not enough ships and crews are available to lay and maintain those cables, we could see bottlenecks and longer outages when breaks occur. Some experts have suggested innovative solutions, like modular robotic repair pods or greater use of satellites as backup, but for now nothing matches the capacity and speed of fiber-optic cables under the sea.

Finally, there is the challenge of international cooperation – or the lack thereof – in a tense geopolitical climate. Undersea cables often run through multiple countries’ waters or through contested seas. Diplomatic spats can delay repairs (for example, if a cable break is in a disputed area, who grants the repair ship permission?). We’ve already seen China reportedly delay approvals for new cables through the South China Sea as a form of pressure Csis. Reaching new agreements on protecting cables – perhaps akin to treaties that protect undersea pipelines – might be necessary. The Joint Statement on undersea cable security by G7 nations and others emphasizes collective responsibility State, but concrete action (like joint naval patrols or information-sharing on threats) will need to follow. For Japan’s part, once it fields its own cable ships, it could offer them to help neighbors’ repairs as a form of “tech diplomacy,” strengthening regional resilience and goodwill.

In conclusion, Japan’s $300 million bet on undersea cable ships is more than an investment in a few vessels – it’s a sign of the times. The world’s powers have woken up to the reality that the internet’s real physical underpinnings lie on the ocean floor, and that these fibers are as strategically important as oil pipelines or shipping lanes. As Japan joins the push to secure and diversify this infrastructure, we are likely to see a more fragmented but fortified global network: one where trusted allies build out their own cable systems and capacity, and where critical data routes are treated as national assets to be defended. Ensuring the lights stay on in our digital world now means sending ships to sea – and Japan is determined not to be left on shore in this new era of cable geopolitics.

Sources:

- Jowi Morales, Tom’s Hardware – “Japan to subsidize undersea cable vessels over ‘very serious’ national security concerns” (Sept. 2025) Tomshardware 14

- Robert Clark, Light Reading – “Japan, India govts ready to tip cash into cable ships” (Sept. 2025) Lightreading 15

- The Asahi Shimbun – “Japan fighting uphill battle in protecting web of undersea cables” (Jan. 2025) Asahi 8

- David Shepardson, Reuters – “US aims to ban Chinese technology in undersea cables” (July 2025) Reuters 16

- Erin L. Murphy & Thomas Bryja, CSIS Report – “The Strategic Future of Subsea Cables: Japan Case Study” (Aug. 2025) Csis 17

- Additional reporting from Financial Times Lightreading and SubOptic Association data 18 .