- The HANTRU-1 cable is 2,917 km long with a 160 Gbps design capacity, extended to Majuro and Kwajalein/Ebeye in 2010, linking to a Pohnpei hub and onward to Guam.

- A 2017 HANTRU-1 cable fault caused a nationwide 3-week outage, forcing a 97% bandwidth cut as the islands relied on limited satellite links.

- The East Micronesia Cable (EMC) project, funded by Japan, Australia, and the US, connects Kosrae (FSM) and Tarawa (Kiribati) to Pohnpei and HANTRU-1, with completion expected around 2025–26 and improved resilience.

- The Central Pacific Cable (CPC) is a 15,900 km subsea link from Guam to American Samoa with Marshall Islands as a landing, expected to operate around 2027–2028 and provide multi-terabit capacity and redundancy.

- In 2022, the Nitijela passed Bill 66 removing NTA’s exclusive rights, ending the monopoly and opening the market, with Starlink approved to operate and available in Majuro, Ebeye, and Kwajalein by 2025.

- SpaceX Starlink began accepting orders in mid-2023 and achieved nationwide service availability in the Marshall Islands by June 2025, with early users reporting speeds above 50 Mbps.

- Intelsat-backed deployment from 2022–2023 added 60 small-cell towers across dozens of atolls, creating a 2G GSM network covering 100% of inhabited islands and enabling voice for about 5,000 residents.

- The Digital Republic of the Marshall Islands Project started in 2021 with a $30 million World Bank grant to expand affordable internet across 24 inhabited atolls, spur private investment, and lay foundations for digital government and cybersecurity.

- As of January 2025, about 24,300 internet users (65.7% of the population), 39,300 mobile connections (107% of population), around 74.6% of households with internet, and 22,700 social media users (61.5% of the population).

- Median fixed broadband speed was 10.2 Mbps in 2022, Majuro speeds by 2024–25 are around 15–20 Mbps, mobile 4G typically 5–12 Mbps, and latency is roughly 50 ms to Guam, 120–180 ms to the US/Asia, with GEO satellite ~600 ms and Starlink ~50 ms.

Internet Infrastructure: Undersea Cables, Mobile and Terrestrial Networks

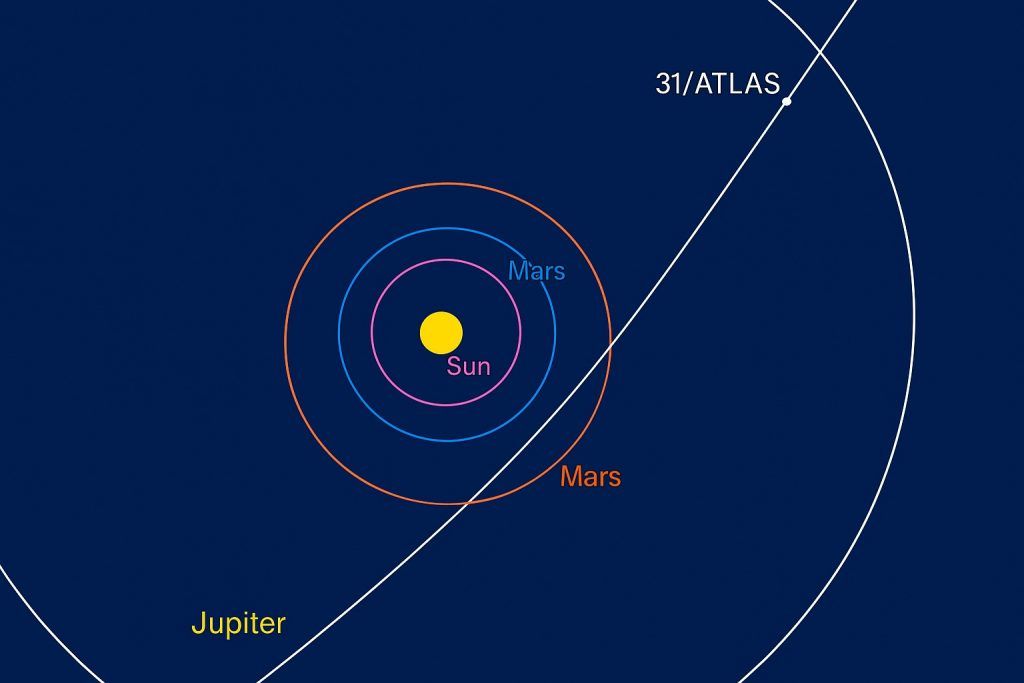

The Marshall Islands’ internet backbone rests on a single submarine fiber-optic cable. In 2010, the HANTRU-1 undersea cable was extended to Majuro and Kwajalein/Ebeye Atolls, linking the country to a hub in Pohnpei (FSM) and onward to Guam dig.watch itu.int. This 2,917 km cable (160 Gbps design capacity) replaced sole reliance on satellites and dramatically improved bandwidth to the capital dig.watch subtelforum.com. However, with only one international cable, connectivity is fragile – a 2017 cable fault caused a nationwide 3-week outage that forced a 97% bandwidth cut as the islands fell back to limited satellite links subtelforum.com subtelforum.com. This highlighted the vulnerability of having “one lifeline” cable. Plans are now in motion to boost resilience: the Marshall Islands is set to benefit from the proposed Central Pacific Cable, a 15,900 km subsea network (backed by the U.S., Australia, Japan) that will connect Guam to American Samoa and branch into up to 12 Pacific nations including the Marshall Islands dig.watch ustda.gov. When realized, this new cable – along with a recently revived East Micronesia Cable project for nearby FSM, Nauru, and Kiribati – will provide much-needed alternate routes and capacity in the late 2020s reuters.com ustda.gov.

On the domestic front, the Marshall Islands National Telecommunications Authority (NTA) maintains all telecom infrastructure. Terrestrial networks are limited by the nation’s geography (29 atolls spread over 1.9 million km² of ocean). Mobile coverage is concentrated in the two urban atolls (Majuro and Kwajalein/Ebeye) and a handful of others. NTA operated a 2G GSM network for years and skipped 3G entirely by launching 4G LTE in Majuro in 2017 itu.int. By 2022, LTE service extended to around 87% of the population itu.int, and NTA has since been working to expand mobile voice and data coverage to outer islands. Traditional fixed-line use is minimal (legacy copper phone lines serve few households itu.int). Instead, fixed broadband is delivered via DSL and fiber in urban centers – ADSL offerings up to ~1.5 Mbps have been available on five atolls, and some businesses and government sites in Majuro have leased lines or fiber connections itu.int. Wi-Fi hotspots also exist in Majuro and Ebeye itu.int. Outside the main centers, most outer islands historically had no modern internet infrastructure; many relied on HF/VHF radio for basic communications marshallislandsjournal.com lca.logcluster.org. This gap is now starting to close as new wireless and satellite-based solutions are deployed (discussed later). Overall, the current infrastructure is a patchwork – a high-speed fiber gateway on two atolls, a growing 4G mobile footprint, and satellite-fed connectivity for remote islands – reflecting the challenging topology of this ocean nation.

Availability, Affordability, and Quality of Service

Internet access in the Marshall Islands has improved in availability, but quality and affordability remain ongoing concerns. Access is highly unequal between urban and rural areas. In Majuro and Ebeye (where ~79% of the population lives datareportal.com), residents can subscribe to broadband or purchase mobile data – though plans have historically been limited and expensive relative to local incomes. Until recently, NTA’s entry-level broadband speeds were extremely low; for example, not long ago the advertised “maximum” basic internet plan was just 384 kbpsntamar.net. While speeds have increased post-cable, costs are still a barrier. As of 2021, the average cost of internet service in the Marshall Islands was estimated at about 4% of GNI per capita pulse.internetsociety.org – meeting the UN affordability benchmark, but this statistic masks the fact that absolute prices (tens of USD per month) are high in a country with modest incomes. In practice, households often pay $30–$50+ monthly for slow connections, and many in outer islands had no option to pay for service at all. Encouragingly, competition from new satellite services is starting to drive prices down (e.g. in nearby FSM, unlimited satellite broadband plans appeared at ~$50/month once the monopoly ended marshallislandsjournal.com, hinting at similar potential for Marshallese consumers).

Service quality has gradually improved but still lags global standards. The introduction of fiber brought broadband to Majuro – by early 2022 median fixed download speed was about 10 Mbps datareportal.com (far below global averages, yet a leap from dial-up days). Mobile 4G speeds are modest as well; users report only a few Mbps in practice, constrained by limited backhaul capacity and coverage gaps. Reliability is another issue: the lone international cable and aging network gear have resulted in periodic outages and slowdowns. For instance, a five-day nation-wide internet disruption in 2022 (caused by technical failures in NTA’s systems) left homes and offices offline until thousands of modems had to be manually reconfigured and networks rebooted marshallislandsjournal.com marshallislandsjournal.com. Such incidents, along with the multi-week 2017 blackout, underscore the fragility of the network. Redundancy is limited – if the fiber cable is down, connectivity reverts to narrow satellite links that cannot support normal data demand subtelforum.com subtelforum.com. Additionally, coverage in outer islands is just beginning; until 2023, remote communities had no data service at all. In short, while internet availability has expanded (over 74% of Marshallese households now have some form of internet access dig.watch), the quality of service (speed, latency, uptime) is uneven and often poor outside the main centers. Efforts are underway to boost both affordability and quality – through sector reforms and new technologies – to ensure the entire Marshall Islands can enjoy reliable, high-speed internet.

Internet Service Providers and Market Competition

For decades, Marshall Islands National Telecommunications Authority (NTA) was the sole ISP and telecom operator by law marshallislandsjournal.com. This government-owned (majority state-owned) company held a monopoly over all telecommunications – fixed, mobile, and internet – as granted by the National Telecommunications Act of 1990. Under monopoly conditions, service options were limited and innovation slow. However, recognizing the need for competition, the government has initiated reforms. In 2022, the Nitijela (parliament) passed a landmark amendment removing NTA’s “exclusive” rights marshallislandsjournal.com marshallislandsjournal.com. Bill 66, a one-word change deleting “exclusive” from the telecom law, officially ended the monopoly and opened the sector to other providers marshallislandsjournal.com. This liberalization push, encouraged by a World Bank-backed reform program, aims to spur private investment and improve services through competition marshallislandsjournal.com. Local leaders noted that similar moves in FSM saw consumers gain access to new satellite broadband offerings at much lower cost, while the incumbent telco remained viable and even strengthened through competition marshallislandsjournal.com.

As of 2025, NTA remains the dominant (and still the only active local) ISP for fixed and mobile services, but the door is now open for new entrants. In practice, the first “competitors” are emerging via satellite internet providers rather than traditional telcos. The regulatory change has allowed international operators like SpaceX Starlink to enter the market directly. Indeed, the government has approved Starlink to operate, and the service is now available for order in at least Majuro, Ebeye, and Kwajalein starlink.com facebook.com. This gives consumers an alternative to NTA’s offerings for the first time – they can independently obtain a high-speed satellite connection. Other satellite players (OneWeb, and SES’s O3b mPOWER for corporate/backhaul use) are also free to offer services, which could further diversify the ISP landscape. Looking ahead, a new competitive licensing regime and the planned establishment of an independent telecom regulator are expected to facilitate additional entrants, possibly a regional mobile operator or private local ISPs. For now, the key development is that Marshallese internet users are no longer locked into a single provider. NTA is adapting to this new environment – focusing on partnerships (it still provides last-mile for some satellite services) and improving customer service – as it faces pressure to cut prices and upgrade networks. The market is small (population ~37k), so it may not attract multiple large telcos, but even limited competition (e.g. NTA vs. satellite-based offerings) is a major shift poised to benefit consumers through better service and pricing marshallislandsjournal.com.

Government Initiatives and Public Access Programs

The Marshallese government, cognizant of the link between connectivity and development, has launched several initiatives to expand internet access and modernize the digital ecosystem. Central to these efforts is the Digital Republic of the Marshall Islands Project, a comprehensive program supported by a US$30 million World Bank grant dig.watch. Begun in 2021, this project’s goals are threefold: (1) Expand affordable internet access across all 24 inhabited atolls, (2) promote private sector investment in climate-resilient digital infrastructure (for example, building redundancies and hardening networks against outages and disasters), and (3) establish the foundations for digital government services and the digital economy documents1.worldbank.org. In practice, the project is funding a public-private partnership approach to infrastructure – assisting the liberalization of the telecom sector and potentially attracting a second operator or strategic partner for NTA marshallislandsjournal.com. It also invests in digital government platforms, cybersecurity, and digital skills training documents1.worldbank.org to ensure that improved connectivity translates into e-government services, online education, and new business opportunities. A Digital Government Office has been set up under the Chief Secretary to drive this agenda, and new laws on data protection, cybersecurity, and digital IDs are being drafted to support the digital transformation documents1.worldbank.org documents1.worldbank.org.

In terms of public access, the government (often with donor support) has rolled out programs to connect schools, healthcare facilities, and community centers. For example, under an arrangement with the U.S. and international partners, many secondary schools now have internet access, and a project is underway to connect all outer island schools via satellite. The recent collaboration with Intelsat enabled community Wi-Fi and phone services in remote villages (small satellite-fed cell stations now provide public calling and internet hotspots on islands that never had them) intelsat.com intelsat.com. Additionally, there are a few Internet cafés and public libraries (notably on Majuro) offering low-cost access, and some local governments have set up “telecenters” for residents to use internet for free or minimal fees (often using satellite links). The government has also pursued universal access initiatives – for instance, subsidizing connectivity for health clinics and setting up free Wi-Fi zones in downtown Majuro. These efforts aim to ensure that even those who cannot afford personal subscriptions can still get online. Finally, recognizing the importance of inclusive access, authorities are working with regional organizations to improve connectivity for persons with disabilities and to localize online content into Marshallese. While these public programs are nascent, they underscore the RMI government’s commitment to bridging the digital divide and leveraging the internet for social development.

Satellite Internet Services: Starlink, O3b, and Other Solutions

Satellites have always played a vital role in Marshall Islands connectivity due to the vast distances and ocean gaps between islands. Until the 2010 fiber cable, 100% of the nation’s internet and international calls were carried over satellites (primarily geostationary Intelsat links) subtelforum.com. Today, satellites continue to provide backup for the cable and are the primary means of connecting outer islands and atolls beyond Majuro/Ebeye. The Marshall Islands is now embracing newer satellite technologies to improve both reach and quality:

- Geostationary (GEO) Satellites: NTA has long partnered with Intelsat (and previously other providers like Intelsat’s predecessor and regional satellite systems). In 2022–2023, Intelsat and NTA executed a major project to bring basic cellular service to the remote outer islands intelsat.com intelsat.com. They deployed 60 small-cell towers across dozens of atolls, each backhauled via Intelsat GEO satellites, effectively creating a 2G GSM network covering 100% of inhabited islands intelsat.com intelsat.com. For the first time, about 5,000 residents in remote communities gained the ability to make phone calls (and limited data) without traveling to the capital intelsat.com intelsat.com. Following the voice phase, a second phase is underway to upgrade these sites to 3G/4G, enabling internet data services countrywide via satellite links intelsat.com. GEO satellites (while having high latency ~600ms) provide a lifeline for these sparsely populated islands where laying subsea fiber or microwave links is not feasible. Additionally, NTA maintains satellite earth stations for international connectivity redundancy – for example, during the 2017 cable outage, Intelsat capacity was ramped up to keep essential traffic flowing subtelforum.com. Other GEO services like Inmarsat and Kacific are also available for specialty use (maritime, emergency broadband, etc.), but Intelsat remains the workhorse for domestic connectivity.

- Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) Satellites: The Marshall Islands is exploring MEO constellations such as O3b (now operated by SES). O3b (orbit ~8,000 km) can deliver fiber-like speeds with ~150 ms latency. Several Pacific neighbors adopted O3b to augment capacity (e.g. nearby Nauru and Kiribati rely on O3b for broadband). While RMI’s main islands haven’t needed MEO due to fiber, there is interest in O3b for backup and perhaps connecting larger outer atolls. As of 2025, no public confirmation exists of O3b terminals in RMI, but the O3b mPOWER satellites coming online promise multi-Gbps links that could be deployed to Majuro or Jaluit as a secondary trunk. The government’s digital strategy explicitly calls for “climate-resilient infrastructure,” which includes non-cable pathways – MEO satellites fit that bill dig.watch dig.watch. We may soon see NTA or a private ISP partner with SES to add MEO capacity, especially as demand outgrows the single HANTRU-1 cable.

- Low Earth Orbit (LEO) Satellites: The biggest buzz is around SpaceX Starlink, the LEO constellation now active in the Marshall Islands. In mid-2023, Starlink started accepting orders locally, and by June 2025 it officially announced service availability in RMI x.com x.com. Starlink’s array of low-flying satellites (~550 km) offers high-speed, low-latency internet even in the middle of the ocean. Early adopters in Majuro report speeds well above 50 Mbps, a game-changer for households and businesses used to 5–10 Mbps on NTA’s network. More importantly, Starlink dishes can be deployed on outer islands (with a clear sky view) to provide broadband where nothing similar existed. Recognizing this, the Marshallese authorities moved quickly to permit Starlink as part of the telecom liberalization. By providing a competing option, Starlink is expected to improve service and drive prices down – even NTA has indicated it may leverage Starlink for island-to-island backhaul or redundancy. Other LEO players like OneWeb and Project Kuiper (Amazon) are also on the horizon and could extend coverage further. OneWeb in particular, which focuses on enterprise and government connectivity, could partner with RMI to connect schools or health centers on distant atolls with high-throughput, low-latency links. In essence, LEO constellations can erase the distance barrier that has long plagued the Marshall Islands.

Overall, satellite internet services are transitioning from a last resort to a core component of the Marshall Islands’ connectivity strategy. They augment capacity, ensure redundancy (so the country isn’t cut off if the fiber breaks), and bring remote islands online. The combination of GEO for broad coverage, MEO for trunk links, and LEO for high-performance connectivity positions the Marshall Islands to overcome its geographic isolation like never before.

Challenges of Geography: Isolation and Low Population Density

Stark geographic realities shape every aspect of internet access in the Marshall Islands. The nation consists of 29 atolls and 5 lone islands scattered over an area of ocean the size of Mexico – but with only ~36,000 people in total datareportal.com. This extreme dispersion presents unique challenges:

- High Infrastructure Costs: Laying fiber or even maintaining microwave links across thousands of kilometers of ocean is prohibitively expensive for such a small user base. For instance, the single HANTRU-1 cable that finally connected Majuro cost around $100 million dig.watch, largely funded by donors. Extending similar cables to outer atolls (some with just a few hundred residents) is economically unviable. Low population density means the per-user cost of any infrastructure is very high. Even terrestrial infrastructure on-island is costly – running fiber or telephone lines beyond the dense downtown areas of Majuro yields little return because villages are small and far apart. This makes operators cautious to invest, resulting in many communities remaining unconnected without subsidy or external aid.

- Remoteness and Logistics: The physical isolation of islands complicates deployment and maintenance of network equipment. Transporting towers, antennas, generators, and technicians to an atoll by boat (sometimes a voyage of days) is logistically challenging intelsat.com intelsat.com. As described in an Intelsat case study, even installing small cellular base stations involved 30-foot utility boats shuttling gear and teams island-to-island, and local crews had to be trained to erect towers when outside experts couldn’t travel due to COVID-19 intelsat.com intelsat.com. Routine maintenance is also a challenge – a satellite dish on a distant atoll might be out of service for weeks until a technician can arrive by ship. This remoteness delays repairs and can lead to longer outages for infrastructure serving remote locations.

- Climate and Environmental Vulnerability: Low-lying atolls face harsh tropical marine conditions. Equipment must withstand corrosive salt air, high humidity, typhoons, and even the threat of sea-level rise. Power supply is another issue – outer islands often lack reliable electricity, so telecom gear needs solar panels or generators, adding complexity. Climate change poses risks to undersea cables as well; warming oceans and more frequent severe weather increase the chances of cable damage (for example, undersea earthquakes or anchor drags in storms). The 2022 volcanic eruption in Tonga (though south of RMI) was a wake-up call about the devastation a natural event can cause to cable infrastructure reuters.com. The Marshall Islands must design its networks with resilience to such events – meaning backup paths (usually satellites) and climate-hardened infrastructure are essential dig.watch.

- Economies of Scale: With a tiny market, the country cannot easily leverage scale for cheaper prices. Bandwidth wholesale costs, satellite capacity leases, and equipment purchases all come at higher unit prices compared to larger countries. There are simply fewer customers to spread costs across. This often results in higher retail prices for consumers and makes it hard for multiple competitors to sustain operations. It also affects content delivery – major content providers have little incentive to place caches or data centers locally, meaning most internet traffic must traverse long distances (e.g. to Guam or Hawaii), adding latency. Low usage volume can also mean the Marshalls get lower priority in global network upgrades, unless advocated for by regional organizations.

Despite these challenges, the Marshall Islands has made notable progress through smart partnerships and external support. Regional cooperation (with larger Pacific neighbors and allies) is helping mitigate the disadvantage of scale – for example, the upcoming Central Pacific Cable pools RMI’s needs with a dozen others to make the project viable ustda.gov reuters.com. Likewise, bulk satellite capacity purchases and shared infrastructure (like the Pacific Islands Internet Exchange) are strategies to overcome isolation. In sum, while geography and demography impose steep obstacles to connectivity, the Marshall Islands is navigating these constraints through innovation, resilience planning, and international collaboration. The challenges are enduring, but they also underscore why robust internet access is so transformative for this remote nation – it truly bridges an otherwise immense divide.

Internet Penetration, Speeds, and Usage Statistics

Internet usage in the Marshall Islands has grown impressively in recent years, though some statistics require careful interpretation due to population shifts. As of early 2025, there are about 24,300 internet users, equivalent to 65.7% of the population using the internet datareportal.com datareportal.com. (For comparison, penetration was only ~39% in 2017 and 38.7% in 2022 datareportal.com itu.int – the jump to ~66% reflects both real uptake and adjustments in population estimates.) The number of mobile connections in use actually exceeds the population – approximately 39,300 mobile subscriptions were active (107% of population) in 2025 datareportal.com. This indicates many people have multiple SIMs or devices, and includes inactive accounts. It also highlights the prevalence of mobile as the primary access mode for internet; over 90% of Marshallese internet users go online via mobile phone. However, only about one-third of those mobile connections are data-capable 3G/4G subscriptions datareportal.com – suggesting a significant share are 2G voice/text only or secondary basic phones datareportal.com. Expanding 4G and affordable data plans is therefore a priority to convert more of the population into active internet users.

Household access is relatively high in the urban centers: roughly 74–75% of households have internet at home (by any means, including mobile broadband) as per recent surveys dig.watch. This is likely much lower in rural outer islands, but national programs aim to close that gap. Social media usage is also robust – there were 22,700 social media users (primarily Facebook) in 2025, about 61.5% of the population datareportal.com. Facebook is by far the most popular platform, with an estimated 20–21k users (almost 90% of internet users) on FB datareportal.com datareportal.com. Other platforms like Instagram (~3.5k users in 2022) and TikTok are smaller but growing among youth datareportal.com. The high social media penetration underscores that once people do have internet access, they actively engage, often using it to connect with the large Marshallese diaspora in the US and elsewhere.

In terms of speed and quality metrics, the Marshall Islands still trails global averages but is improving. As mentioned, median fixed broadband download speed was 10.2 Mbps in 2022 datareportal.com; by 2024–25, anecdotal reports suggest median speeds in Majuro might be in the 15–20 Mbps range, especially with new fiber upgrades and the option of Starlink (which can deliver 50–150 Mbps). Mobile network speeds on 4G have been measured in the range of 5–12 Mbps (download) under good conditions, though official data is scarce. Latency on the terrestrial internet (via the fiber cable) to Guam is around ~50 ms, but overall latency to US or Asian servers is closer to 120–180 ms – decent for the Pacific. On satellite links, latency is much higher: ~600 ms on GEO, ~150 ms on MEO, and ~50 ms on Starlink LEO (comparable to fiber). International bandwidth per user was reported at only ~38 kbit/s in 2017 itu.int, but thanks to capacity upgrades, this has increased substantially – NTA now has multiple Gbps of bandwidth to the global internet, translating to hundreds of kbit/s per user (still low by world standards, but no longer a strict choke point).

One concerning statistic was the low fixed broadband subscription rate – around 2 per 100 people in 2017 itu.int. This reflects the fact that most households didn’t have a wired broadband subscription, instead relying on shared mobile or Wi-Fi. That figure has likely risen with more LTE wireless broadband offerings; still, fixed wired broadband remains uncommon outside businesses and government offices. The focus is on mobile and wireless solutions to boost penetration.

It’s also worth noting usage patterns: with limited bandwidth, usage has been centered on communication (Facebook, WhatsApp), basic web browsing, and light video consumption. As speeds improve, more Marshallese are using e-learning platforms, streaming YouTube and Netflix, and exploring e-commerce and digital banking (the national bank launched online banking services in recent years as connectivity grew). According to one report, about 73% of individuals had used the internet in some form by 2023 dig.watch, indicating that the majority of the populace has at least occasional access, even if not at home (some use workplace, school, or community connections).

In summary, the Marshall Islands’ internet statistics paint a picture of a nation rapidly coming online: strong mobile adoption, rising internet and social media penetration, but also clear room for growth in quality and reach. With continued investments, those usage numbers are expected to keep climbing – ideally toward universal internet access in the coming decade.

(See Table 1 for a summary of key indicators.)

Table 1 – Marshall Islands Connectivity at a Glance (2025)

| Indicator (Jan 2025) | Value / Status |

|---|---|

| Population | ~36,900 datareportal.com |

| Internet users | 24,300 (65.7% penetration) datareportal.com datareportal.com |

| Mobile connections (SIMs) | 39,300 (107% of population) datareportal.com |

| Households with internet access | ~74.6% dig.watch |

| Social media users | 22,700 (61.5% of population) datareportal.com |

| Undersea fiber-optic cables | 1 active (HANTRU-1, since 2010) dig.watch |

| International satellite gateways | 2+ (Intelsat as primary; others as backup) |

| Mobile network coverage | Majuro/Ebeye: 4G LTE; Outer islands: 2G (voice) expanding to 3G/4G intelsat.com |

| Median fixed broadband speed (2022) | 10.2 Mbps download datareportal.com |

| ISP market structure | Monopoly ended 2022; NTA + Starlink (entrant) marshallislandsjournal.com x.com |

Recent Developments and Future Connectivity Projects

The past few years have seen significant developments, and the near future holds promising projects aimed at boosting the Marshall Islands’ connectivity:

- HANTRU-1 Cable Upgrades: NTA has been upgrading the equipment on the existing HANTRU-1 cable to increase its capacity and lifespan. Since its 2010 launch, technology improvements now allow greater throughput than the original 20 Gbps lit capacity. Upgrades in 2021–2023 (new terminal equipment) have expanded available bandwidth, enabling higher speeds for users and more redundancy. These upgrades helped support the surge in demand during the COVID-19 pandemic when bandwidth usage spiked due to greater reliance on remote communications.

- East Micronesia Cable (EMC): Although the Marshall Islands is not directly on the EMC route, this project is regionally important. Funded by Japan, Australia, and the US after an initial controversy (it was rebid to exclude Chinese vendors), the EMC will connect nearby FSM (Kosrae) and Kiribati (Tarawa) to Pohnpei (and thus into HANTRU-1) pacificislandtimes.com pacificislandtimes.com. The cable, now contracted to NEC and underway as of 2023, will indirectly benefit the Marshall Islands by improving the resilience of the broader Micronesian network. It means multiple cable pathways in the neighborhood, which could provide emergency backup possibilities. EMC’s completion (expected ~2025–26) will add another piece to the Pacific submarine cable web in which RMI is embedded.

- Central Pacific Cable (Guam–American Samoa): This is the big future project on the horizon for the Marshall Islands. The Central Pacific Cable (CPC), now in feasibility study stage with a USTDA grant, will be a huge 15,900 km subsea cable linking Guam to American Samoa and connecting up to 12 Pacific nations along the way ustda.gov ustda.gov. The Marshall Islands is slated to be one of the landing points. Likely, a spur will connect Majuro to the main CPC trunk, giving RMI a second independent route out (complementing HANTRU-1). This would be the first time Majuro is connected to a network not transiting through FSM, which is strategic for redundancy. The CPC is envisioned to bring high-speed internet to underserved countries like Tuvalu, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands, and is part of a broader geopolitical effort to offer “trusted” infrastructure in the Pacific reuters.com reuters.com. If all goes to plan, the cable could be operational around 2027–2028. For Marshall Islands, CPC’s arrival will be transformative – providing much greater capacity (multi-terabit) and critically, a backup path if the other cable fails. It will also create opportunities for price competition in international transit, hopefully lowering wholesale bandwidth costs.

- Starlink and Satellite Expansion: In the immediate term, the rollout of Starlink is a major development (as noted). By late 2024, Starlink beta units were already in use, and in 2025 the service is officially live nationwide x.com. We can expect increasing adoption, especially by businesses, government offices, and tech-savvy households. The government is even considering using Starlink to connect outer island dispensaries and police outposts that currently have only radio. Additionally, OneWeb’s upcoming global coverage (possibly by 2024/25) could see OneWeb ground terminals deployed for cellular backhaul, improving mobile data capacity on remote atolls. The Intelsat 3G/4G rollout (phase 2 of their project) is also a near-term development – scheduled to begin in mid-2023 and continue through 2024 intelsat.com. This means that by 2025, many outer islands will get 3G data service for the first time, enabling basic internet on cellphones in those communities.

- National Fiber and Microwave Links: Within Majuro, a modest fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) deployment has started, connecting government buildings and some businesses with gigabit fiber links. NTA has indicated plans to expand fiber connectivity on Majuro (which is a long thin atoll ~50 km long). There is also discussion of a microwave radio link between Majuro and the secondary population center, Ebeye (Kwajalein Atoll), as a backup to the subsea cable. However, given the 460 km distance, this would require island-hopping repeaters and is still conceptual. Instead, a microwave link was completed to connect Majuro with the remote Laura settlement on the western end of the atoll, improving connectivity there.

- Regulatory and Policy Framework: A softer development but crucial: the creation of a new Office of the Telecommunications Regulator (as envisaged in the 2012 National ICT Policy itu.int and enabled by the 2022 law). By 2024, the government was in the process of establishing an independent regulator to oversee licenses, spectrum, and competition. This institution will help manage the transition to a competitive market and ensure quality of service standards. Moreover, digital policy developments – like a Cybersecurity Strategy and updated ICT laws – are being rolled out under the Digital Republic project documents1.worldbank.org. In 2025, the government introduced the Digital Transformation and Identity act, aiming to boost e-government and trust in online transactions dig.watch. All these policies create a more enabling environment for improved connectivity and digital services.

- Regional Connectivity Initiatives: The Marshall Islands continues to engage in regional forums like the Pacific Islands Telecommunications Association (PITA) and the Declaration for the Future of the Internet initiative dig.watch dig.watch. Through these, it seeks partnerships and funding for projects such as extending rural connectivity and exploring alternative tech (like HF radio Internet, drone/balloon-based signal relays, etc.). One recent example (2025) is a partnership with the Global Partnership for Education to use digital connectivity for remote schooling, highlighting how new bandwidth can be channeled into social programs globalpartnership.org.

In summary, the Marshall Islands stands at a turning point. After years of being a relatively isolated pocket of the internet, these new projects – second submarine cables, next-gen satellites, network upgrades, and reforms – are set to drastically improve the robustness and reach of the country’s internet access. If successful, the next few years will see higher speeds, lower costs, and internet access extending to virtually every household from Majuro to the smallest outer islet. For a nation spread across the sea, this digital connectivity is not just a convenience but a lifeline – enabling everything from telemedicine and education to economic diversification. The Marshall Islands is embracing the tools to overcome its isolation, ensuring its people can fully participate in the global digital community from the middle of the Pacific.

Sources: Marshall Islands Digital Watch Observatory dig.watch dig.watch; Submarine Telecoms Forum subtelforum.com subtelforum.com; Pacific Island Times pacificislandtimes.com pacificislandtimes.com; Reuters reuters.com reuters.com; USTDA Press Release ustda.gov ustda.gov; Marshall Islands Journal marshallislandsjournal.com marshallislandsjournal.com; Intelsat (May 2023) intelsat.com intelsat.com; DataReportal 2025 datareportal.com datareportal.com; ITU/ICT Country Profile itu.int itu.int; APNIC Blog reuters.com; CIA World Factbook; Marshall Islands Govt. documents.