December 25, 2025 — The United States has formally moved toward new tariff action on Chinese semiconductors, but with a major twist: the tariff rate is set at 0% for now and won’t rise until June 23, 2027, giving companies an 18‑month runway to adjust supply chains while Washington tries to keep a fragile détente with Beijing intact. Reuters

The policy—announced by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) after a yearlong Section 301 investigation—lands in the middle of a broader U.S.–China technology and trade tug‑of‑war that has increasingly centered on chips, critical minerals, and the industrial capacity that powers everything from automobiles to AI. Reuters

On December 25, China issued its strongest official pushback yet. A Commerce Ministry spokesperson said Beijing “firmly opposes” the additional Section 301 tariffs, called the U.S. move a violation of WTO rules, and warned China would take “necessary measures” if Washington proceeds. Xinhua News

What the U.S. actually decided: a tariff now, but priced at zero

USTR’s notice is explicit: the United States is taking tariff action now on semiconductors from China, but the initial tariff level is 0%, and it will increase in 18 months—on June 23, 2027—to a rate that will be announced at least 30 days beforehand. United States Trade Representative

That structure is unusual in headline terms—“tariffs imposed” and “tariffs delayed” are both true—because the legal mechanism is being put in place immediately while the financial hit is deferred. Reuters framed the decision as preserving the ability to impose duties while dialing down near‑term escalation. Reuters

USTR also points to a longer arc: the investigation found China has targeted semiconductor dominance for decades and used an expansive set of industrial plans and targets to pursue it. In the notice, USTR describes more than 100 industrial plans and highlights a previously public market share ambition aiming to capture 56% of international sales and 80% of domestic sales. United States Trade Representative

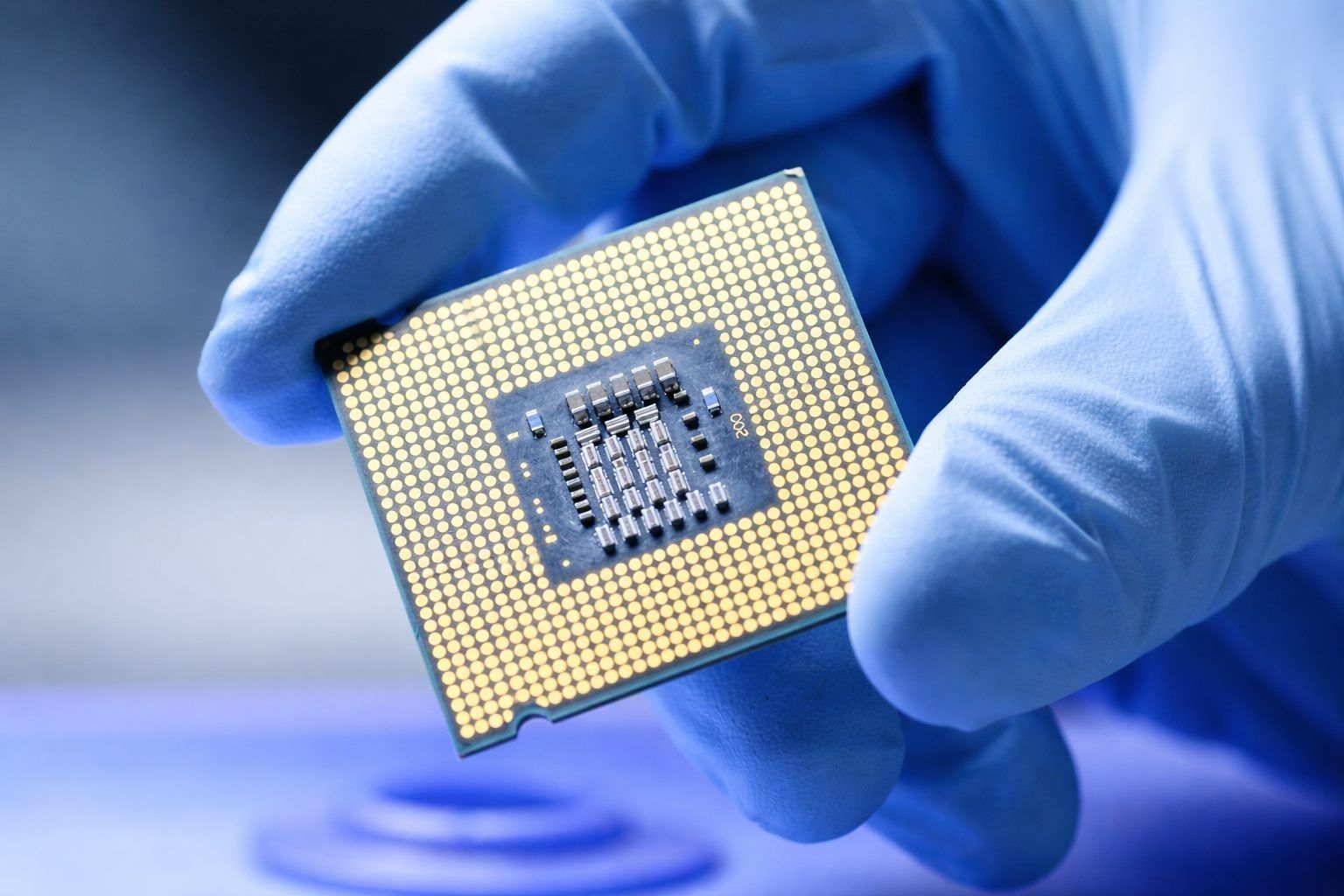

The chips in scope: components and integrated circuits that underpin “everyday” tech

The Section 301 investigation was launched on December 23, 2024, and looked at China’s semiconductor policies—including where Chinese chips are incorporated into downstream products used in critical sectors such as defense, automotive, medical devices, aerospace, telecommunications, and power generation/the electrical grid. United States Trade Representative

The tariff action, as described in the USTR notice, maps to specific tariff classifications covering semiconductor devices and integrated circuits—such as parts of diodes/transistors and related semiconductor devices, and electronic integrated circuits including processors/controllers, memories, amplifiers, and other ICs, plus parts. United States Trade Representative

In practical terms, this is a policy aimed at the “plumbing” of modern electronics—widely used chips and components that may be less glamorous than bleeding‑edge AI accelerators, but are foundational across industries. Reporting tied the action to concerns about “legacy” or “mature-node” chips, which are ubiquitous in vehicles, industrial equipment, telecom hardware, and countless consumer devices. Reuters

Why delay until 2027: leverage, truce politics, and minerals

The timing—setting a future escalation rather than an immediate hike—has been widely interpreted as strategic restraint in a relationship that has swung between tariff brinkmanship and tactical bargaining.

Reuters reported that the delay is meant to preserve a China trade truce while the U.S. confronts Chinese export curbs on rare earth metals used across the tech economy. Reuters

That minerals dimension matters because Beijing has demonstrated its willingness to use supply‑chain chokepoints as geopolitical tools. USTR’s notice itself references China’s use of export restrictions on critical minerals like gallium, germanium, and antimony, warning that over‑reliance can create vulnerabilities and coercion risks. United States Trade Representative

The tariff pause also fits into a broader set of reciprocal moves that have characterized the current phase of U.S.–China economic diplomacy. A White House fact sheet on the Trump–China trade deal describes Chinese commitments to suspend or ease certain export controls (including rare earths and other critical materials) and U.S. steps to suspend or extend certain trade measures, framing the relationship as managed competition rather than nonstop escalation. The White House

China’s response on December 25: WTO claims and a warning shot

China has been signaling resistance since the announcement, but December 25 brought a more formal, Commerce‑Ministry‑level statement.

According to China’s state news agency Xinhua, a Ministry of Commerce spokesperson said China disagrees with the U.S. Section 301 conclusions, firmly opposes additional tariffs on Chinese semiconductor products, and urged the U.S. to revoke the measures—arguing unilateral tariffs violate WTO rules and disrupt global supply chains. Xinhua News

The spokesperson also said China lodged “stern representations” through a China–U.S. economic and trade consultation mechanism and warned that if the U.S. insists on harming China’s rights and interests, Beijing will take “necessary measures.” Xinhua News

A day earlier, China’s foreign ministry had already criticized what it called Washington’s “indiscriminate use of tariffs” and “unreasonable suppression” of Chinese industries. Reuters

The Trump–Xi truce backdrop: stabilizing trade while fighting over tech

The tariff decision isn’t happening in isolation. It sits inside a wider U.S.–China posture where both sides are selectively easing pressure in some areas while intensifying competition in others.

A December 25 report in The Star described the tariff delay as another signal the Trump administration is trying to stabilize ties and reinforce the deal Trump and Xi struck in South Korea, including commitments to relax some export restrictions on technology and critical minerals. The Star

At the same time, the Trump administration is keeping multiple “pressure points” in reserve—tools that can be activated quickly if the relationship deteriorates. The delayed chip tariff is one; other tools include export controls, entity restrictions, and broader tariff authorities. Reuters

How this intersects with Nvidia and U.S. export controls

The chip tariff story is also colliding with a separate, politically charged debate: whether the U.S. should allow sales of advanced AI chips to China.

Reuters has reported an inter‑agency review that could lead to the first shipments to China of Nvidia’s H200 AI chips, following Trump’s pledge to allow sales with the U.S. government collecting a 25% fee. Reuters

The proposal has drawn bipartisan criticism from China hawks concerned about military and AI implications. Two senior Democratic lawmakers urged the Commerce Department to disclose details of any approvals and demanded briefings before licenses are granted. Reuters

This matters for the tariff story because it underscores the administration’s dual track: de‑escalate tariffs to protect supply chains and diplomacy, while recalibrating tech controls in ways that could reshape U.S. leverage and China’s access to key computing components. Reuters

What businesses should take from the 18‑month runway

Even with a 0% rate today, companies that touch semiconductors—importers, electronics manufacturers, automakers, industrial OEMs, and distributors—are now staring at a clear policy marker: June 23, 2027.

The real corporate question is less “Will tariffs rise tomorrow?” and more:

- How high will the rate be in 2027—and will it stack on existing duties?

Reuters noted the U.S. already has an additional 50% tariff on Chinese semiconductors that began January 1, 2025, and trade specialists have described the new action as an additional layer that can be increased later. Reuters - Which product categories are most exposed?

USTR’s action targets semiconductor devices and integrated circuits in defined tariff categories—components that can sit deep inside supply chains rather than as consumer-facing finished goods. United States Trade Representative - How do you “China+1” a mature-node chip?

Mature-node capacity is spread globally, but China’s scale—and the cost advantages associated with industrial policy—has made it hard to replace quickly in certain categories without increasing prices or extending lead times. The policy’s delayed design arguably acknowledges that reality: you can’t flip the switch overnight without collateral damage. Financial Times

In other words, the 18‑month window is not a free pass—it’s a planning deadline.

What to watch next: three dates and two investigations

If you want the forward-looking roadmap, it clusters around a few concrete triggers:

- Between now and mid‑2027: the U.S. can adjust posture through negotiations, sector actions, or additional restrictions—without the new chip tariff immediately biting. Reuters

- At least 30 days before June 23, 2027: USTR must publish the tariff increase rate in a Federal Register notice. United States Trade Representative

- June 23, 2027: the deferred increase date currently written into the action. United States Trade Representative

Two broader policy processes could also change the playing field sooner:

- A Section 232 national security probe into global chip imports, which Reuters said could expand tariffs across a much wider set of electronics and countries—though U.S. officials have suggested it may not result in immediate new levies. Reuters

- Ongoing U.S. export-control decisions (including Nvidia licensing), which can shift real-world chip flows faster than tariffs can—especially for advanced computing. Reuters

The bottom line on December 25: a pause that still raises the stakes

The most important takeaway from today’s news cycle is that the U.S. and China are not stepping away from the semiconductor fight—they are re‑timing it.

Washington has declared China’s semiconductor push “actionable” under Section 301 and built a mechanism for higher tariffs, but postponed the cost impact until 2027—effectively turning tariffs into a delayed bargaining chip. Reuters

Beijing, in turn, is contesting both the legal rationale and the economic impact, with China’s Commerce Ministry framing the move as a WTO violation and warning of countermeasures—while leaving the door open to dialogue. Xinhua News

For companies, investors, and policymakers, the message is clear: the next chapter of the chip-and-minerals rivalry won’t necessarily be written in a single dramatic tariff hike. It will be shaped by a sequence of deadlines, licensing calls, and negotiations—starting now, and culminating in a tariff rate that the world won’t know until the countdown to June 23, 2027 is nearly over. United States Trade Representative