When most people hear “space propulsion,” they picture fire and chemical exhaust. But one of Australia’s most closely watched propulsion efforts is built around something far less cinematic—and potentially far more practical for modern satellites: a solid metal rod of molybdenum that can be turned into plasma on demand to nudge spacecraft through orbit.

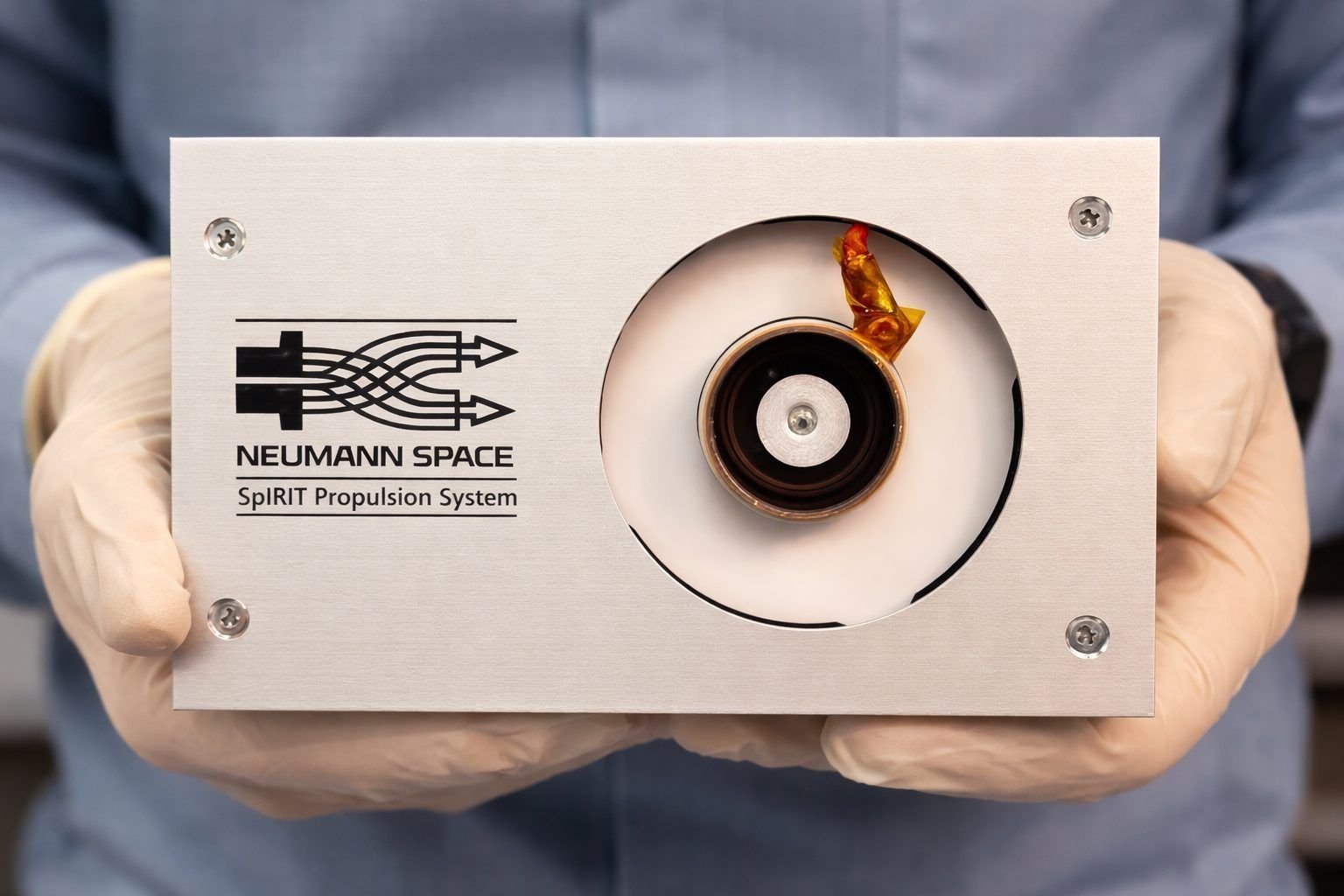

That technology, developed by Adelaide-based Neumann Space, has moved beyond lab demonstrations and into repeated on-orbit testing—an important step in a market that increasingly expects satellites to dodge debris, maintain formation, and safely deorbit at end of life. Over the past two years, the company’s Neumann Drive has progressed from first launch to multiple in-space firings, including demonstrations on Australia’s SpIRIT nanosatellite and ESA-linked missions in Europe. 1

Below is what “molybdenum-fueled space propulsion” actually means, why it’s gaining attention now, and how Neumann Space’s growing flight heritage fits into the new reality of crowded, regulated Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

What “molybdenum-fueled” propulsion really means (and what it doesn’t)

First, a crucial clarification: this is not a launch engine. Neumann Space is working in the world of in-space electric propulsion, the class of thrusters used after a satellite is already in orbit. These systems don’t blast a spacecraft off the pad; they provide small, efficient pushes for tasks like:

- orbit raising and trimming

- station-keeping (staying in the right place)

- collision avoidance

- controlled deorbiting at end of mission

The novelty is the propellant. Traditional electric thrusters often rely on pressurized tanks of gas (commonly xenon, krypton, or newer options like iodine). Neumann Space’s approach uses solid metal propellant, with molybdenum used in key flight tests. In 2024, for example, Australia’s SpIRIT spacecraft conducted test firings that “demonstrated the ability to use Molybdenum as a solid metallic propellant,” after charging the propulsion system’s capacitors from solar panels and onboard batteries. 1

Neumann Space’s propulsion method is generally described as a pulsed cathodic arc approach that converts a solid conductive “fuel rod” into plasma to create thrust—meaning the “fuel” is better understood as a solid propellant feedstock than a chemical fuel in the everyday sense. 2

The Neumann Drive: turning a solid metal rod into thrust

Neumann Space’s system is typically explained as a lightweight, solar-electric propulsion unit designed to be integrated on small satellites. The South Australian Space Industry Centre (SASIC) describes the Neumann Drive as using a solid metallic propellant rod and a patented Centre-Triggered Pulsed Cathodic Arc Thruster (CTPCAT) approach to generate thrust. 2

Why design around a solid metal rod?

Because it changes the practical realities of satellite propulsion:

- Storage and handling: a solid propellant can be simpler to transport and store than a pressurized tank.

- Integration speed: fewer fluid lines and pressure hardware can reduce integration complexity for smallsat builders.

- Safety and logistics: solid propellants may simplify certain ground operations and launch logistics compared to high-pressure systems.

Neumann Space has repeatedly framed the Neumann Drive as intentionally built for simplicity across the full lifecycle—from integration through operations. 3

NASA’s Small Spacecraft Technology “State-of-the-Art” propulsion overview explicitly lists the Neumann Drive as a center-triggered pulsed cathodic arc technology using molybdenum propellant, offered in multiple configurations depending on spacecraft power. 4

Why molybdenum? The metal choice that helped make flight testing possible

Molybdenum is not a common headline word, but it’s a serious engineering material: strong at high temperatures, widely used in industrial applications, and—critically for this use case—conductive and compatible with plasma-generation approaches.

Neumann Space’s public messaging around its first launch emphasized that molybdenum was selected as an “optimal” metal for its pulsed cathodic arc thruster testing, while also pointing to the longer-term potential for using other metals (including recycled metals already in orbit) as future propellant rods. 5

That future-facing idea—propulsion that can eventually run on in-space sourced metals—has become a recurring theme in the company’s partnerships and commercialization pitch.

The news timeline: from first launch to repeated on-orbit firings

Neumann Space’s molybdenum-propellant story is best understood as a sequence of escalating milestones, with each step designed to build the “flight heritage” that satellite operators and insurers often demand before adopting a new propulsion system.

March 2023: first integration on an Australian satellite (Skykraft)

In March 2023, Space Connect reported Neumann Space had integrated its Neumann Drive—using a solid metallic molybdenum propellant—onto a Skykraft satellite for the first time, ahead of a mid-June U.S. launch. 6

The core pitch even then was aligned with today’s market pressure: satellites need propulsion to deorbit, maneuver away from debris, and operate more deliberately in crowded orbits. 6

June 2023: first space launch on SpaceX Transporter-8

Neumann Space’s first in-orbit demonstrator launched from Vandenberg aboard SpaceX’s Transporter-8 rideshare mission. Space & Defense reported liftoff at approximately 7:05am on 13 June (ACST), with the propulsion unit containing molybdenum propellant and based on the company’s pulsed cathodic arc thruster technology. 7

Around the same event, InDaily described the Neumann Drive as a rod-based thruster sent up specifically to test molybdenum as a propellant in “real world” conditions. 5

December 2023: first series of on-orbit tests and a key “first”

By early December 2023, multiple outlets reported Neumann Space had completed its first series of on-orbit tests and successfully fired a molybdenum-propellant thruster in space—framed by the company as a commercial first for this propellant approach. 3

SpaceDaily’s coverage highlighted the goals of those early tests: validate electronics, charge the system’s power capacitors, and execute test firings—establishing the baseline confidence needed for follow-on missions. 3

August 2024: SpIRIT nanosatellite demonstrates molybdenum firings in orbit

A major credibility boost arrived in August 2024 via the Australian Space Agency, which reported that SpIRIT successfully completed on-orbit tests of the Neumann Drive and conducted “several test firings” demonstrating molybdenum propellant use. 1

The Agency described the moment as a milestone for an “Australian electric propulsion system” using solid metal propellants, with testing expected to continue through the remaining two-year mission timeline. 1

January–March 2025: ND‑50 on EDISON, firings under ESA Pioneer programme

In 2025, focus shifted to the next-generation ND‑50 variant flying on EDISON, a mission tied to the European Space Agency’s Pioneer programme.

Space & Defense reported EDISON launched 14 January 2025 on SpaceX Transporter‑12, and that Neumann Space subsequently fired the ND‑50 multiple times on different orbits, with “nominal” parameters. 8

Australian Defence Magazine likewise reported the company had completed initial testing and successfully fired the system quickly after commissioning—quoting Neumann Space CEO Herve Astier: “We are thrilled to achieve this first success with Space Inventor.” 9

SASIC described EDISON as the Neumann Drive’s third flight, emphasizing the CTPCAT mechanism and the collaboration with Danish satellite manufacturer Space Inventor. 2

The Australian Space Agency, looking back at the Transporter‑12 rideshare launch period, noted Neumann Space integrated the ND‑50 as an in-orbit demonstration payload onboard the 8U EDISON satellite, manufactured by Space Inventor, and tied to ESA’s Pioneer programme. 10

August 2025: Neumann Space expands into the United States

In a move that signals commercialization intent beyond pure R&D, SASIC reported that Neumann Space announced a U.S. expansion at the 39th Annual Small Satellite Conference in Utah, appointing Jason Wallace as Vice President for Business Development. 11

SASIC also reiterated the company’s central claim: the Neumann Drive converts a solid metal fuel rod into plasma to produce thrust, and it is already flying on missions including SpIRIT and EDISON. 11

Why this propulsion push is happening now: debris, congestion, and tougher rules

The timing of Neumann Space’s flight campaign is not accidental. The smallsat boom has turned LEO into a more tightly managed environment, where “no propulsion” increasingly means “no go” for many mission profiles.

One major driver is regulation around end-of-life disposal. In the United States, the FCC adopted a “5-year rule” for deorbiting satellites in low Earth orbit—shortening the long-standing 25-year guideline and requiring faster post-mission disposal. 12

Regardless of where a satellite is built, these rules matter because many operators need access to U.S. spectrum licensing—or sell services into markets where compliance expectations are rising. The practical consequence is straightforward: more satellites need reliable, compact propulsion, especially in the nanosat and smallsat classes where mass and volume are scarce.

This is exactly the segment Neumann Space has targeted since the beginning: standardized propulsion units designed to add mobility without forcing satellite teams to redesign their entire spacecraft bus. 6

Beyond molybdenum: the “circular propulsion” idea of turning space debris into fuel

One of the most attention-grabbing angles in the Neumann Space story isn’t just what the Neumann Drive uses today—it’s what it could use tomorrow.

In 2023, U.S.-based CisLunar Industries announced a $1.7 million U.S. Space Force (SpaceWERX) contract focused on recycling metal in space to enable “enhanced satellite mobility,” describing a “circular propulsion ecosystem.” Neumann Space was identified as a partner providing its propulsion system for the project. 13

In a related CisLunar release, the companies described an agreement under a U.S. Space Force-funded project to operationalize recycling of metal in space into metallic fuel for propulsion—with the Neumann Drive selected due to its solid metallic propellant approach. 14

And one of the most vivid lines came from CSU’s Center for Electric Propulsion and Plasma Engineering, comparing the concept to everyday sustainability: “Converting space debris to propulsion fuel rods is like using your compost pile to fuel your car.” 13

Whether this becomes a mainstream reality will depend on in-space manufacturing maturity, economics, and policy. But it shows why metal-propellant propulsion has become such a compelling narrative: it links mobility and sustainability in a way that traditional pressurized propellant supply chains struggle to match.

What comes next: proving performance at scale, and winning operator trust

By late 2025, Neumann Space’s core achievement is that it has moved from “interesting concept” into “tested in orbit on multiple missions,” including:

- early demonstration missions beginning with Skykraft-linked testing in 2023 6

- molybdenum firings and capacitor-charging demonstrations on SpIRIT in 2024 1

- ND‑50 firings on EDISON in 2025 under an ESA Pioneer umbrella 8

That said, commercialization in propulsion typically comes down to operator confidence in areas that aren’t always obvious from headline milestones:

- repeatability across many firings over long periods

- predictable thrust and efficiency across power levels

- plume interactions and spacecraft contamination considerations

- ease of integration into standardized satellite buses

- manufacturing consistency and supply chain scaling

Neumann Space’s public comments indicate the company sees ongoing in-orbit testing as the bridge from demonstration to broader adoption—building the “assurance and confidence” that customers demand. 1

The U.S. expansion announcement suggests the company is now leaning into that next stage: translating flight heritage into contracts in the world’s largest commercial and government smallsat market. 11

The bottom line

Neumann Space’s molybdenum-fueled space propulsion effort is not a flashy rocket-engine story—it’s a satellite-mobility story, built around a deceptively simple idea: replace complex tanks and valves with a solid metal “fuel rod,” then use electricity to turn it into plasma thrust when needed.

In an era of congested orbits, rising deorbit expectations, and rapidly growing satellite constellations, that kind of pragmatic propulsion—especially when repeatedly demonstrated in orbit—can be the difference between a satellite that merely survives in LEO and one that can actively operate there.

If you want, I can also rewrite this into a tighter 700–900 word Google Discover version (same facts, punchier pacing) or tailor the angle toward defense applications, sustainability, or Australia’s sovereign space industrial base—without adding charts, images, or a meta description.