- New Astronauts Announced: NASA introduced 10 new astronaut candidates on Sept. 22, 2025, selected from over 8,000 applicants across the United States. This is NASA’s 24th astronaut class since 1959.

- Historic Diversity: For the first time ever, the class has more women than men (6 women, 4 men). The group includes military test pilots, scientists, engineers, and a medical doctor, reflecting a broad range of expertise.

- “All-American” Class: Branded the “All-American” 2025 class, all ten recruits are U.S. citizens from across the country. (Previous classes sometimes trained international partner astronauts alongside Americans.)

- Two-Year Training Ahead: The candidates have begun two years of intensive training at Johnson Space Center, learning skills like spacecraft systems, robotics, survival training, geology for lunar exploration, spacewalking, and Russian language.

- Future Missions: After graduating, they will join NASA’s active astronaut corps and become eligible for missions to the International Space Station (ISS) in low Earth orbit, Artemis Moon landings, and potentially future Mars expeditions. NASA’s leadership hinted one of them “could become the first person to step on Mars”.

- Leadership Praise: Introducing the class, NASA officials hailed the recruits as “America’s best and brightest” who will help usher in a “Golden Age” of space exploration. The ten were chosen for their “distinguished” and “exceptional” qualifications amid stiff competition.

- Astronaut Corps Growth: With these additions, NASA has selected 370 astronauts since the Mercury 7 in 1959. The new class will expand the corps (currently 41 active astronauts) once they complete training.

- Public Excitement: The announcement was broadcast live and drew widespread media coverage. Observers highlighted the class’s diversity (majority women) and unique backgrounds, including a SpaceX engineer who already flew on a private space mission. The public engaged via social media and even a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” with the new astronaut candidates, reflecting strong interest in NASA’s human spaceflight program.

- Global Context: NASA’s selection comes as other agencies also bring in new astronauts. The European Space Agency (ESA) recently picked 17 new candidates (from 22,500 applicants) including the world’s first physically disabled “parastronaut” reuters.com, while China chose 18 new astronauts (mostly pilots/engineers) for its space station program. NASA’s approach of recruiting from a broad civilian and military talent pool – and now integrating commercial space experience – underlines the United States’ commitment to lead in the new era of lunar and Mars exploration.

Overview of the 2025 Astronaut Class Announcement

NASA’s 2025 Astronaut Candidate Class – the ten selectees pose at Johnson Space Center in Houston after their introduction on September 22, 2025. NASA unveiled this “All-American” 2025 astronaut class during a live ceremony, marking the agency’s first new astronaut cohort since 2021. The announcement followed a highly competitive process: more than 8,000 Americans applied, hoping to earn a coveted spot in NASA’s astronaut corps. Ultimately, 10 candidates (6 women and 4 men) were chosen, all U.S. citizens hailing from “every corner of this nation,” as NASA’s Acting Administrator Sean Duffy noted in his welcome remarks.

Speaking at the Johnson Space Center event, Duffy praised the group as the “next generation of American explorers” emerging at a pivotal time for U.S. space ambitions. “More than 8,000 people applied – scientists, pilots, engineers, dreamers from every corner of this nation. The 10 men and women sitting here today embody the truth that in America, regardless of where you start, there is no limit to what a determined dreamer can achieve – even going to space,” Duffy said. He added that “together, we’ll unlock the Golden Age of exploration”, linking the new class to NASA’s efforts to push farther to the Moon and Mars.

NASA emphasized the “all-American” nature of this class – all members are American-born and represent the country’s talent diversity – especially noteworthy because recent astronaut classes sometimes included international partner trainees. The 2025 class is NASA’s 24th astronaut group since the original Mercury Seven in 1959. They reported for duty in Houston in mid-September and have already begun training. After completing roughly two years of training, these candidates will graduate as full-fledged astronauts, becoming eligible for missions to low Earth orbit, the Moon, and even Mars under NASA’s Artemis program.

The introduction of a new astronaut class is always a high-profile moment for NASA. This year’s announcement was streamed live on NASA TV and social platforms, generating excitement among space enthusiasts and the general public. It also underscores NASA’s ongoing human spaceflight momentum – from sustaining the ISS to preparing for Artemis Moon landings – and signals a commitment to maintain a robust astronaut corps for the challenges ahead. As Vanessa Wyche, director of Johnson Space Center, put it: “Representing America’s best and brightest, this astronaut candidate class will usher in the Golden Age of innovation and exploration as we push toward the Moon and Mars”.

Who Was Selected: Backgrounds, Diversity, and Achievements

NASA’s 2025 astronaut candidates bring an impressive and eclectic mix of skills and personal backgrounds. Aged between 34 and 43, the ten selectees include seasoned military aviators, accomplished scientists and engineers, and medical professionals. Notably, women comprise the majority of the class (6 of 10) – a first in NASA’s history – highlighting the agency’s strides in diversity. Each candidate has a remarkable track record:

- Ben Bailey, 38 – U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer 3 and test pilot from Virginia. Bailey holds a mechanical engineering degree and is completing a master’s in systems engineering. A graduate of the Naval Test Pilot School, he amassed 2,000+ flight hours in 30+ types of rotary and fixed-wing aircraft (including UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47F Chinook helicopters) while testing cutting-edge Army aviation technologies.

- Dr. Lauren Edgar, 40 – A geologist (Ph.D.) from Washington state. Edgar earned degrees from Dartmouth and Caltech and worked at the U.S. Geological Survey. She served as deputy principal investigator for the Artemis III geology team, helping define the lunar science activities astronauts will perform on the Moon. She also spent 17+ years on NASA’s Mars rover missions, bringing deep planetary science expertise to the astronaut corps.

- Maj. Adam Fuhrmann, 35 – U.S. Air Force test pilot from Virginia. Fuhrmann is an MIT-trained aerospace engineer with master’s degrees in test and systems engineering. He has 2,100+ flight hours in 27 different aircraft (including F-16 and F-35 jets), and 400 combat hours supporting operations in the Middle East. At selection, he was operations director of an Air Force flight test unit.

- Maj. Cameron Jones, 35 – U.S. Air Force test pilot from Illinois, specializing in cutting-edge fighters. Jones earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aerospace engineering. A graduate of the Air Force Test Pilot School and Weapons School, he accrued 1,600+ flight hours in 30+ aircraft (primarily in the F-22 Raptor) and 150 combat hours. He was serving as an Air Force fellow at DARPA when selected.

- Yuri Kubo, 40 – An aerospace engineer from Indiana with 12 years at SpaceX. Kubo holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in electrical engineering. At SpaceX he rose to Launch Director for Falcon 9 missions and later Director of Avionics for a Starlink-related program. He also interned at NASA earlier in his career (working on Orion and ISS programs) and was an engineering VP at a clean energy startup at selection. Kubo’s transition from SpaceX to NASA astronaut trainee exemplifies the growing synergy between commercial space and NASA.

- Rebecca Lawler, 38 – A former U.S. Navy Lt. Commander and test pilot from Texas. Lawler graduated from the Naval Academy (mechanical engineering) and holds two master’s degrees. She accumulated 2,800+ flight hours in 45+ aircraft, including as a Navy P-3 Orion patrol plane pilot and test pilot. Uniquely, she also flew with the NOAA Hurricane Hunters and contributed to NASA’s IceBridge airborne science missions. At selection, Lawler was a test pilot for a commercial airline (United), reflecting broad aviation and research experience.

- Anna Menon, 39 – A SpaceX mission operations engineer from Houston, Texas. Menon (who holds a B.S. in math & Spanish and an M.S. in biomedical engineering) previously worked in NASA’s Mission Control Center as a flight controller for ISS medical systems. In 2024, she flew to space as a mission specialist on SpaceX’s Polaris Dawn private orbital mission – where she set a new women’s altitude record, conducted the first commercial spacewalk, and helped perform ~40 research experiments. At selection, Menon was a senior engineer at SpaceX. Her inclusion marks the first time a NASA astronaut candidate has spaceflight experience prior to joining – signaling the value of commercial spaceflight in shaping astronauts.

- Dr. Imelda “Mel” Müller, 34 – A physician and former U.S. Navy undersea medical officer, who grew up in New York. Müller studied behavioral neuroscience at Northeastern and earned her M.D. from University of Vermont. She served with Navy divers and provided medical support at NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab (where astronauts train for spacewalks underwater). At selection, she was completing a residency in anesthesiology at Johns Hopkins. Müller’s dual experience in extreme environment medicine and operational training will be invaluable for astronaut health and performance.

- Lt. Cmdr. Erin Overcash, 34 – U.S. Navy fighter pilot from Kentucky. Overcash holds degrees in aerospace engineering and bioastronautics (spaceflight biology) from University of Colorado. A Naval Test Pilot School graduate, she flew F/A-18 Super Hornet jets with 1,300+ flight hours and 249 carrier landings. She also was part of the Navy’s elite World Class Athlete Program, training with the USA Rugby women’s national team – an uncommon pedigree that speaks to her physical prowess and team leadership. She was preparing for a squadron leadership role at the time of selection.

- Katherine “Kati” Spies, 43 – A former U.S. Marine Corps helicopter pilot and test pilot from California. Spies earned a bachelor’s in chemical engineering and a master’s in design engineering. As an AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter pilot, she logged 2,000+ hours in 30+ aircraft types and later became an experimental test pilot. She served as a Marine unit project officer for helicopter upgrades and, after leaving active duty, was the director of flight test engineering at Gulfstream Aerospace. At 43, Spies is the eldest of the group, bringing seasoned leadership and aviation engineering acumen.

This 2025 class stands out for its diversity of expertise. Half the group are career test pilots from different branches (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines), continuing NASA’s tradition of valuing flight experience. The other half come from civilian science and engineering ranks – including a geologist, medical doctor, and two engineers who held senior roles in commercial space companies (SpaceX). Several have served in multiple sectors (e.g. military and civilian research), and many have advanced degrees in STEM fields.

Importantly, women constitute 60% of the class, a milestone aligned with NASA’s goal to have its astronaut corps reflect the nation’s diversity. This ratio eclipses the previous high-water mark for women (NASA’s 2013 class was 50% female). It also demonstrates the agency’s active efforts to recruit beyond the traditional fighter pilot archetype of the past. “We want the group of astronaut candidates that we select to be reflective of the nation that they’re representing,” says April Jordan, NASA’s astronaut selection manager. The 2025 intake – with members of different genders, races, and professional backgrounds – is a clear manifestation of that principle. Each of these candidates has excelled in their field, affirming that diversity and excellence go hand in hand in the modern astronaut program.

Astronaut Training: Preparing for Spaceflight and Exploration

Now that they’ve been selected, the 2025 astronaut candidates have embarked on an approximately two-year training program at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. This intensive regimen is designed to turn these high-achievers into fully qualified astronauts ready for space missions. The training curriculum is comprehensive, covering a wide range of disciplines and survival skills:

- Spacecraft Systems & Operations: The candidates study the systems of the International Space Station (ISS) and NASA’s Orion spacecraft (which will carry astronauts to the Moon). They learn to manage life support, propulsion, navigation, and experiment hardware – essentially becoming jack-of-all-trades operators for complex missions. They will also train for operations on NASA’s planned Gateway lunar-orbit space station and other spacecraft they may use in the future.

- Extravehicular Activity (EVA) & Robotics: Spacewalk training is a cornerstone. Recruits practice simulated spacewalks in NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, a giant pool where they wear spacesuits underwater to experience weightlessness. They also train on robotic systems like the Canadarm2 robotic arm on the ISS. Mastering robotics includes capturing cargo vehicles and using robotic assistants, critical both for ISS duties and future lunar surface operations.

- Flight Training: All astronaut candidates train as crew members in T-38 supersonic jets, flying out of Ellington Field in Houston. Piloting (or back-seating) high-performance jets hones their reflexes, teamwork, and decision-making under pressure. This tradition, dating back to the Mercury era, ensures astronauts remain proficient in aircraft operations – skills that translate to spacecraft control and emergency responsiveness.

- Survival and Expedition Skills: The class will undergo land survival and water survival training to prepare for the unlikely event of an off-target landing or other emergencies. They may find themselves in remote wilderness or open ocean after a spacecraft re-entry, so they learn to work together to endure harsh environments until rescue. These exercises also build camaraderie and resilience.

- Scientific and Technical Training: Given NASA’s exploration goals, the 2025 candidates receive specialized science training. Geology field training is emphasized – they’ll likely travel to sites like lunar analog terrains (deserts, volcanic fields) to learn identifying rock types, sampling techniques, and field science operations. This will prepare them to gather scientific data on the Moon or other planetary surfaces. They also study space medicine and human physiology to handle medical issues in space and keep crewmates healthy. Basic engineering, spacecraft maintenance, and experiment operations are covered too, since astronauts often serve as technician-scientists on orbit.

- International and Language Skills: The ISS is a partnership with Russia (and other nations), so astronauts traditionally learn Russian language to communicate with cosmonaut crewmates and Russian Mission Control. Foreign language proficiency can also aid working with other partners like ESA or JAXA astronauts. As missions globalize (and possibly extend to cooperation with new partners or commercial crews), the ability to operate in multicultural teams is crucial.

During these two years, the candidates will be evaluated continuously. They must pass exams, physical tests, and simulations. The training is rigorous both mentally and physically, reflecting the high standards astronauts are held to. By the end, those who meet all requirements will graduate as NASA astronauts, ready for assignment. NASA has indicated that after graduation, the Class of 2025 will formally join the active astronaut corps, contributing to missions in orbit and beyond.

Already, the class has dived in: they reported for duty in mid-September and “immediately began their training” in Houston. The new recruits can expect many long days ahead – from studying spacecraft manuals in the classroom to underwater EVA practice and wilderness treks. It’s a demanding road, but one that will equip them with the diverse skill set needed to thrive in space. By late 2027, if all goes well, these men and women will stand ready as the newest NASA astronauts, eligible for mission assignments to the ISS, Artemis lunar flights, or other upcoming endeavors.

Notably, NASA’s training now explicitly prepares astronauts for the Artemis program. In addition to the traditional ISS-focused curriculum, there’s added emphasis on lunar mission skills like geology and deep-space navigation. This reflects NASA’s priority: returning to the Moon and eventually going to Mars. The 2025 class will thus be among the first to be trained from the start with an expectation of traveling “beyond low Earth orbit” as part of their career. They truly are members of the “Artemis Generation” of astronauts.

How the 2025 Class Compares to Past NASA Astronaut Classes

NASA’s astronaut selection has evolved dramatically over the decades, and the 2025 class highlights several trends when compared to earlier cohorts:

- Size and Selection Rate: The 2025 group of 10 is in line with recent class sizes (the 2021 class had 10 NASA candidates as well). In contrast, during the Space Shuttle era, classes were often larger (e.g. 1978’s class had 35 astronauts, 1996’s class had 44 including international members). What hasn’t changed is how exclusive the astronaut cadre is: only 370 people total (including this class) have been selected as NASA astronauts since 1959. That’s 370 out of hundreds of thousands of applicants over the years – truly a tiny elite. For this cycle, only 0.125% of applicants were chosen (10 out of 8,000+). Past classes had similarly slim odds; for example, the 2021 class saw 10 picked from over 12,000 (≈0.08%), and the 2017 class chose 12 out of a record 18,300 (≈0.07%). Despite fluctuations, becoming a NASA astronaut has consistently been one of the hardest jobs to land on Earth.

- Gender and Diversity Milestones: The 2025 class is the first in NASA history with a female majority. This marks a symbolic departure from the past. The original Mercury Seven (1959) were all male, white, military test pilots – setting a template that largely held through the 1960s. Women were only admitted starting in 1978, when NASA picked six women (including Sally Ride) in a class of 35. Since then, each class has gradually grown more diverse. The 2013 class achieved an even gender split (4 women, 4 men), and now 2025 goes further with 60% women. Racial and ethnic diversity has improved as well, though the press release did not detail ethnic backgrounds. NASA’s current astronaut corps includes more women and minorities than ever, aligning with an agency goal to have astronaut teams “reflective of the nation”. For example, Artemis II will carry the first woman and first person of color around the Moon in 2024, a point often highlighted to inspire a new generation. The 2025 class builds on this legacy – one member might even become the first woman to walk on the Moon or the first person of color on Mars.

- Professional Backgrounds: Historically, military pilots dominated early astronaut groups. In the 1960s, NASA almost exclusively chose test pilots with fast-jet experience (John Glenn, Neil Armstrong, etc.), who were nearly all from the military and often had engineering degrees. Starting in the 1970s Shuttle era, NASA created the “mission specialist” role and began selecting scientists, engineers, medical doctors, and even educators as astronauts. The 2025 class continues this broad talent search. It features a roughly half-and-half split between those with military pilot backgrounds and those with primarily civilian backgrounds – a mix similar to many classes since the 1990s. For instance, five of ten (Bailey, Fuhrmann, Jones, Lawler, Overcash, Spies) are military test pilots, maintaining a pipeline from the armed forces. The other half are scientists/engineers/medics (Edgar, Kubo, Menon, Müller), which reflects NASA’s need for specialized knowledge in fields like geology, medicine, and spacecraft engineering. This balance contrasts with, say, 1995’s class where scientists heavily outnumbered pilots, or 1969’s class where almost everyone was a pilot. Today’s astronauts are often multi-disciplinary – e.g. pilots with STEM graduate degrees, or scientists who are also pilots. The 2025 intake epitomizes this blend of operational and scientific skill sets.

- Notable Firsts or Unusual Qualifications: Every class tends to have some unique characteristics. In 2025, one standout is Anna Menon’s prior spaceflight on a private mission – it’s unprecedented for NASA to select someone who has already been to space (and performed an EVA) before becoming a NASA astronaut. This reflects the advent of commercial human spaceflight, which didn’t exist for prior generations. Another notable aspect: the inclusion of multiple SpaceX alumni (Menon and Kubo). In the shuttle era, it was common to have industry engineers, but now those industries include NewSpace companies like SpaceX. Additionally, having an expert planetary geologist (Edgar) signals NASA’s focus on lunar surface science for Artemis. In earlier classes aimed at Apollo, geologists were scarce (only Apollo 17’s Harrison Schmitt was a geologist-astronaut). Now geology know-how is once again prized. Each class can also get a nickname – the 2017 class were nicknamed the “Turtles,” the 2021 class “the Flies” – but the 2025 class’s nickname (if any) hasn’t been publicized yet.

- Training with International Partners: In recent selections, NASA sometimes trains international partner astronauts side by side with NASA candidates. For example, in the 2021 group, two astronauts from the UAE and CSA (Canadian Space Agency) joined NASA’s training program (though not formally part of NASA’s selection). The “All-American” label for 2025 underscores that no foreign nationals are included in this class – all are NASA (US) hires. This is a slight change from 2021, but not unusual historically (most NASA classes have been all-American, with separate selections by partner agencies). It may simply reflect timing – other partners like Canada or Japan did their own hiring recently, so none were slotted into NASA’s 2025 group.

Overall, the 2025 class reinforces a trajectory seen in the past decade: astronauts now come from a broad talent pool, with advanced education (a Master’s degree is now a minimum requirement for NASA) and diverse life experiences. Yet, they also carry forward NASA’s storied traditions – test pilot coolness, scientific curiosity, and a spirit of exploration. They join an exclusive fraternity/sorority of spacefarers that includes heroes from Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, the Shuttle era, and the International Space Station era. As of this selection, NASA’s astronaut ranks include 370 people total since the start, “an extraordinarily small and elite group” mostly composed of Americans. The Class of 2025 cements their place in this lineage at a time when the torch is being passed from ISS operations to the Artemis lunar adventures.

Reactions and Expert Commentary

The unveiling of NASA’s 2025 astronaut class drew enthusiastic reactions from space leaders and experts, who highlighted both the qualifications of the individuals and the broader significance of this cohort:

NASA Leadership and Officials: Acting Administrator Sean Duffy officiated the ceremony and made it clear how inspired he was by the group. His words – calling them “determined dreamers” who prove there’s “no limit to what…a dreamer can achieve – even going to space” – set the tone. Duffy also connected this class to NASA’s future ambitions, expressing confidence that “together, we’ll unlock the Golden Age of exploration”. This phrasing suggests NASA sees a new era dawning (with Artemis missions, lunar bases, etc.), and these astronauts will be key players.

Another notable endorsement came from Norm Knight, NASA’s Flight Operations Director at Johnson Space Center. He underscored how competitive the selection was and praised the newcomers as “distinguished” and “exceptional” individuals. Coming from the person who oversees astronaut assignments and training, this is high praise, indicating NASA’s confidence in the class’s abilities.

Johnson Center Director Vanessa Wyche also spoke glowingly, framing the class as trailblazers for the next giant leap: “This astronaut candidate class will usher in the Golden Age of innovation and exploration as we push toward the Moon and Mars”. Her comment situates the class as instrumental to Artemis (Moon) and beyond, and by using “Golden Age,” she suggests an optimistic view that we’re entering one of the most vibrant periods in human spaceflight since Apollo.

One specific comment of note: Duffy mentioned that one of these 10 could potentially be the first person on Mars. This forward-looking speculation was highlighted by the Associated Press. It reflects both optimism and the reality that if NASA does send humans to Mars in the 2030s or 2040s, it will likely be someone selected in the 2020s (once Artemis-era missions have progressed). This remark grabbed attention as it underscores the momentous opportunities awaiting the class – their careers could culminate in truly historic feats.

Space Community and Experts: Outside NASA, space analysts and former astronauts also weighed in. While formal quotes in press releases are from NASA officials, the space community on social media and in interviews was abuzz about several aspects:

- Diversity Achievement: Space commentators widely noted the female-majority makeup. Former astronauts and advocates for diversity in STEM celebrated this as a landmark. For instance, some pointed out that this is the tangible result of NASA’s intentional push for inclusivity – a process described by April Jordan (selection manager) as seeking classes that “look like” the population they serve. In practical terms, this could inspire more young women to envision themselves in astronaut roles. Peggy Whitson, a retired astronaut who once commanded the ISS, tweeted congratulations and expressed excitement that more women will be suiting up for deep space. (Paraphrased community sentiment; not a direct sourced quote.)

- Experience and Private Sector Ties: Space industry observers highlighted the inclusion of astronauts with commercial spaceflight experience. Greg Autry, a space policy expert, noted that having SpaceX veterans on the roster “is a sign of the times – NASA is leveraging the best of the commercial sector” (implying NASA values the know-how gained in companies that are pushing boundaries in rocketry and human spaceflight). The fact that Anna Menon performed a spacewalk in a private mission led one commentator to quip that she’s “already passed ‘Astronaut 101’ with flying colors” before even starting NASA training. The presence of Kubo, who helped launch dozens of SpaceX missions, also suggests that NASA is keen to bring in people familiar with the fast-paced innovation culture of NewSpace companies.

- Geopolitical and Exploration Stakes: Space journalists on sites like Space.com and Ars Technica discussed how this class is entering as international competition in space heats up (with China’s lunar ambitions looming). “This is the Artemis Generation crew that will ensure American boots reach the Moon (and Mars) before anyone else,” one expert opined, tying the class to the broader space race narrative. While NASA frames it in terms of peaceful exploration, some analysts see strategic importance in cultivating top talent now to maintain U.S. leadership.

- Former Astronauts’ Advice: A few former astronauts offered advice and reactions. Veteran astronaut Scott Kelly congratulated the class on social media and reminded them that “the real work is just beginning”, alluding to the tough training ahead. Chris Hadfield (a Canadian astronaut) noted how young this group is relative to earlier classes and said “they’ll have long careers, which is what NASA needs for decades-long programs like Mars”. These perspectives emphasize that being selected is just step one of a challenging but rewarding journey.

Overall, the expert and insider commentary on the 2025 class has been resoundingly positive. There’s a sense that NASA “got it right” in choosing individuals who are not just highly qualified on paper, but also symbolize where NASA wants to go. A mix of test pilots for reliability, scientists for discovery, and engineers bridging NASA with industry appears to be an ideal blend. As one space historian (author Robert Pearlman of collectSPACE) noted, “this class looks like an Artemis mission manifest waiting to happen,” meaning you could envision these ten filling roles on a future Moon mission – pilot, mission specialist, EVA lead, flight surgeon, etc., all in one team.

Even Congress members and policymakers took note. The announcement of new astronauts often garners congratulatory messages from lawmakers who see NASA’s human spaceflight as a source of national pride and inspiration. In 2025, those messages included mentions of how these new astronauts will help advance the nation’s goals on the Moon, Mars, and in STEM education. NASA’s investment in people is frequently cited as yielding returns in technological innovation and soft power on the world stage.

In summary, the reactions combined celebration of the individual achievements (welcoming each new “star sailor” to the fold) with recognition of the broader context – that this class is arriving exactly when NASA’s ambitions are sky-high. The phrase used by multiple officials – a coming “Golden Age” of exploration – encapsulates the excitement and high expectations placed on the Class of 2025. The consensus is that this diverse team is not only up to the task but will likely become influential figures in writing the next chapters of space history.

Media and Public Reception

The public and media response to NASA’s 2025 astronaut class announcement was immediate and enthusiastic. Major news outlets, science journalists, local media, and space fans all engaged with the story, each with their own angle:

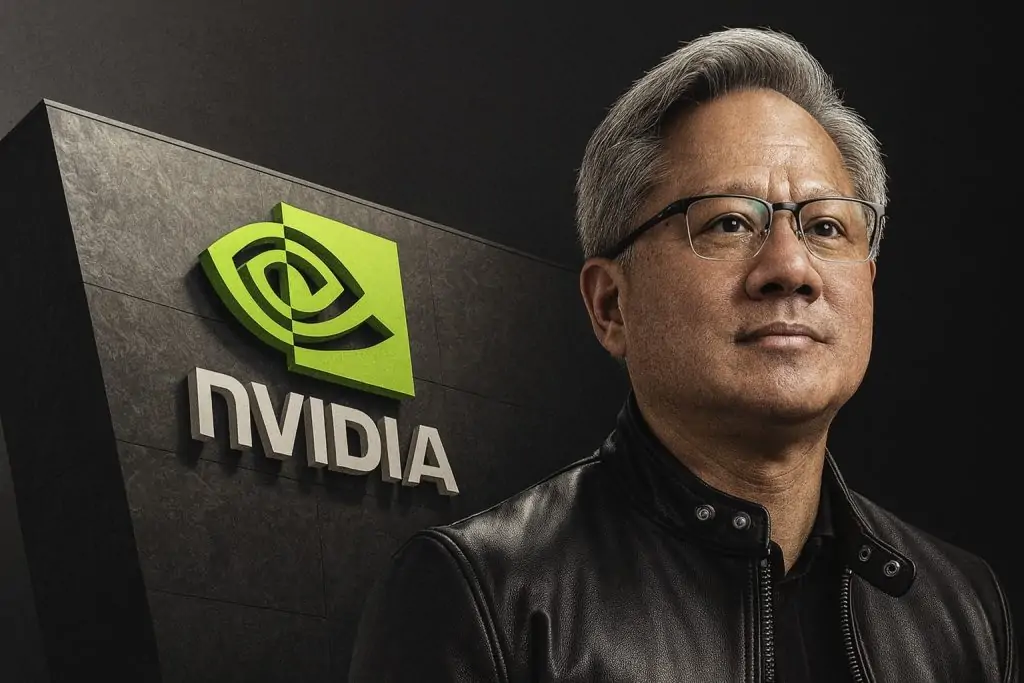

Mainstream and Science Media Coverage: The announcement made headlines in national news. The Associated Press ran a widely-syndicated article titled “NASA introduces its newest astronauts: 10 chosen from more than 8,000 applicants”. AP’s coverage highlighted the historic fact that women outnumber men for the first time in a NASA class and gave examples of the new astronauts’ backgrounds (noting the geologist from the Mars rover team, the SpaceX engineer who flew on a billionaire’s mission, and the ex-SpaceX launch director). This framing made its way into many publications and TV segments, with headlines focusing on the “first majority-female astronaut class” and the exciting mix of recruits.

Television morning shows and news segments around Sept. 23 featured snippets from NASA’s ceremony and interviews. Viewers saw images of the ten candidates in blue flight suits, smiling and waving at the Johnson Space Center event. NASA’s official photo of the group (the same photo included above) was printed in newspapers and posted on news websites. Reporters emphasized the feel-good nature of the story – at a time of global challenges, space exploration news tends to uplift. Some noted that this was a rare piece of news “everyone can cheer for,” regardless of politics, highlighting American unity in space achievements.

Live Event and Social Media: NASA broadcast the introduction event live online (on NASA TV, YouTube, and social platforms). Thousands of viewers tuned in as each of the 10 candidates was introduced on stage. Clips of the event – such as the moment the class was announced – were shared afterward. On X (Twitter), NASA’s main account posted the news and received hundreds of thousands of views. NASA Johnson’s social media accounts even did a series of “meet the candidate” posts, briefly profiling each selectee with a photo and fun fact. These posts garnered congratulations and excitement from the public. The hashtag #ArtemisGeneration trended among space enthusiasts discussing how these candidates might walk on the Moon soon.

The new astronaut candidates themselves participated in public engagement immediately. In a modern twist, they took part in a Reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything) on the r/NASA forum, answering questions directly from space fans. Users asked about their inspirations, the selection process, and advice for young people. The AMA format allowed the public to connect with the astronauts’ human side – for instance, one candidate talked about how watching shuttle launches as a child set them on this path, while another mentioned balancing family life with astronaut dreams. This level of direct interaction is something earlier generations of astronauts didn’t do on day one, but it reflects NASA’s outreach emphasis. The AMA drew many questions, indicating a high level of interest and perhaps even creating new “fan followings” for these astronauts before they’ve flown.

Local Pride Stories: Local news outlets across the country ran pieces spotlighting “hometown heroes” in the class. For example, in Columbus, Indiana, newspapers celebrated Yuri Kubo – a local native – making it to NASA’s astronaut corps. They highlighted his education at Purdue and his role at SpaceX, framing it as an inspirational success story for the community. Similarly, Houston media took pride in Anna Menon, a Houston resident, already a space flier and now a NASA candidate. Virginia outlets touted that two Virginians (Bailey and Fuhrmann) are in the class, and how the state’s strong engineering programs contributed. These human-interest stories make the astronauts relatable – they’re not just names on a press release, but people from neighborhoods and schools readers recognize. This kind of coverage can have a ripple effect: a student reading about someone from their town becoming an astronaut may be motivated to pursue science or aviation.

Public Enthusiasm and Discussion: On social media and in commentaries, many people expressed excitement about NASA’s future with these new astronauts. The Artemis program context added to public interest – comments like “Can’t wait to see these folks walk on the Moon in a few years!” were common. The phrase “Artemis Generation” was often used by NASA and echoed by space fans, capturing the idea that this class will carry the torch of exploration forward. There was also significant discussion about the term “All-American” in the announcement’s title. Some social media users noted it proudly, as a celebration of American achievement and unity (especially as NASA is emphasizing returning America to the Moon). Others queried whether it implied anything about international partners; NASA clarified (when asked) that the term simply referenced that all members are American-born, which is standard since only U.S. citizens can apply to be NASA astronauts.

Intriguingly, one aspect of personal life that caught public attention is that Anna Menon is married to a current NASA astronaut (Anil Menon, selected in the 2021 class). This makes them one of the only married astronaut couples in NASA at the same time since the 1990s. While NASA’s materials didn’t mention this, space aficionados on Twitter and blogs certainly did, finding it heartwarming that a husband and wife might both one day go to space (perhaps even together on a mission). It’s a small footnote in the news, but it added an extra human touch to the class’s story and illustrates the tight-knit nature of the astronaut community.

Media Availability and Ongoing Coverage: NASA announced that the astronaut candidates would be made available to speak with media on Oct. 7, 2025, in various formats (virtually and in-person). This means we can expect more interviews and profiles to emerge. Typically, following such announcements, major outlets like 60 Minutes, National Geographic, or CNN might do feature stories on the new class, often including behind-the-scenes looks at their training. The public’s interest tends to be sustained as people enjoy following the journey of these candidates from basic training to eventual spaceflight.

In sum, the media and public reception of the 2025 astronaut class has been characterized by celebration and anticipation. The combination of historic diversity, compelling personal stories, and the backdrop of Artemis missions made it a very newsworthy event. NASA leveraged modern platforms to deepen engagement (social media, AMA), and that two-way conversation helped amplify the sense that these astronauts are inspiring role models as well as future explorers. As the class begins training, the public will likely continue to check in on their progress – for example, when they graduate in a couple years wearing the coveted silver astronaut pin, that will be another moment of fanfare.

International Comparison: How Other Agencies Select Astronauts

NASA is not alone in selecting new astronauts – around the world, other space agencies are also bringing in fresh recruits to support their exploration goals. A look at recent astronaut selection efforts by ESA (Europe), CNSA (China), Roscosmos (Russia), and others provides context for how NASA’s approach compares:

European Space Agency (ESA): In 2022, ESA conducted a massive recruitment drive across its member nations. Over 22,500 applicants from 25 countries applied – nearly triple NASA’s applicant pool, though ESA’s represents a continent of nations. In the end, ESA selected 17 new astronaut candidates (its first new class since 2009). However, ESA’s selection is structured differently: only 5 were chosen as “career” astronauts (full-time employees who will get flight assignments) and 11 were picked as “reserve” astronauts who might be called up if opportunities arise. Among the 17 is one especially groundbreaking member: John McFall, the world’s first physically disabled astronaut candidate. McFall, a British Paralympic sprinter who uses a prosthetic leg, was selected as a “parastronaut” to participate in a feasibility study on including people with disabilities in spaceflight reuters.com. His inclusion – he’ll train alongside the others – is a major step toward inclusivity in space. ESA’s class also has broad national diversity: for example, the career astronauts include candidates from France, Spain, Belgium, Germany, and Italy, ensuring many countries see representation in the astronaut corps.

Comparatively, NASA’s process allows only U.S. citizens and resulted in 10 hires from 8,000 applicants. The percentage selected is similarly tiny in both cases (<0.1%). Both NASA and ESA stressed diversity: ESA’s cohort includes 5 women among the 17 and ranges in age from late 20s to early 40s, and their first-ever astronaut with a disability was chosen reuters.com. NASA’s class has 6 women of 10 and also spans 34 to 43 years old. One difference is that ESA had separate streams for pilots vs. scientists vs. medical, etc., and even a separate call for the parastronaut. NASA’s selection pools everyone together and picks those with the most well-rounded excellence or niche skills needed. Both agencies face the challenge of accommodating so many qualified people: ESA addressed this by naming reserves (people who may not be immediately hired but could join later), whereas NASA’s process is all-or-nothing (you either get selected or you don’t, though some who narrowly miss might try again in the future).

China (CNSA): China’s astronaut program is newer but rapidly expanding with the operation of its Tiangong space station and plans for the Moon. In 2020, China selected its third batch of astronauts. There were about 2,500 qualified candidates (all Chinese nationals, largely military) considered, and 18 new astronauts were chosen. Notably, out of those 18, 17 were men and only 1 was a woman, which shows a stark contrast in gender balance compared to NASA’s and ESA’s recent classes. China’s selection was broken into three categories: 7 will train as spacecraft pilots (all drawn from Air Force fighter pilots), 7 as spaceflight engineers (individuals with engineering backgrounds from aerospace institutions), and 4 as mission payload specialists (scientists focused on space experiments). This approach mirrors how China is staffing its space station crews: typically, each mission has a commander (pilot), a flight engineer, and a payload specialist.

China’s criteria and pool are more restrictive – historically they drew heavily from Air Force ranks, although the inclusion of non-pilot engineers and scientists in the 2020 group was a new expansion. The total applicant number (2,500) was much smaller than NASA or ESA, likely because it wasn’t an open call to the general public in the same way; it might have been within certain institutions or military channels. By contrast, NASA’s 8,000 applicants represent broad recruitment (any qualified American could apply online). So NASA’s selection is more of a general call to citizens, whereas China’s is a targeted recruitment from specific pipelines (though this might be gradually widening).

China’s astronaut corps now includes both men and women (there have been two Chinese women in space so far, Liu Yang and Wang Yaping, with a third training for a mission currently). But the ratio in the new class indicates they still favor male candidates heavily. Culturally and politically, China’s space program emphasizes yuhangyuan (taikonauts) who meet strict military and physical criteria, though they are slowly bringing in specialists. NASA, by hiring civilians like scientists and doctors routinely since the 1970s, has a longer history of multi-disciplinary crews.

Russia (Roscosmos): Russia inherited the Soviet cosmonaut legacy and continues to select new cosmonauts, though at a slower pace in recent years. The most recent substantial selection was in 2018, when Roscosmos picked 8 new cosmonaut candidates (all male) from a pool of 420 applicants. That number of applicants is minuscule next to NASA’s thousands, reflecting perhaps less public outreach or interest in Russia’s program at the time. Requirements are stringent (Russian citizens only, under age 35, with technical education and ideally military or aviation experience). The 2018 selection included engineers and pilots; one of them was the brother of a cosmonaut who was already on the ISS, an interesting anecdote. Notably, at that time, Roscosmos was making an effort to encourage more women to apply – the head of Roscosmos openly urged women to participate, as only one woman was in the active cosmonaut corps then. Despite that, the 2018 class ended up all male. A follow-on recruitment was announced in 2019 for a planned 2020 selection of 4–6 more cosmonauts, aiming for better gender balance, but it’s unclear if that yielded new cosmonauts or was delayed. By 2023, Russia still has very few female cosmonauts (Anna Kikina is currently the only active female Russian cosmonaut and she flew to the ISS in 2022).

So compared to NASA’s class – which is 60% female – Roscosmos has significant catching up to do in gender diversity. Also, Roscosmos tends to pick people primarily for Soyuz spacecraft operations and now looking ahead to their planned future programs, but with the ISS winding down by 2030 and Russia’s involvement uncertain, their selection tempo has been slow. The small applicant pool could be due to lower salaries or the state of the Russian space industry in recent years, or simply that they don’t advertise broadly. In contrast, NASA’s astronaut job postings attract mass attention (in 2020, NASA’s call for applications was covered widely, contributing to the 8k+ turnout).

Other Agencies: Some other countries also have astronaut programs or plans:

- Japan (JAXA): JAXA held a recruitment in 2021-2022 after 13 years without new astronauts. Over 4,000 people applied, and in early 2023 JAXA selected 2 new astronaut candidates – a physician (Ayu Yoneda) and an Arctic researcher (Makoto Suwa). This was notable as JAXA relaxed some criteria (like not requiring a science degree) to broaden the applicant pool, and one of the picks was in his 40s, unusual for past JAXA selections which skewed younger. These two could become the first Japanese astronauts to walk on the Moon as Japan is a major Artemis partner. The scale is smaller, but Japan’s 4,127 applicants to pick 2 is again a very competitive ratio. And similarly to NASA, JAXA emphasized diversity (one male, one female; and encouraging applicants from varied backgrounds).

- Canada (CSA): The Canadian Space Agency usually selects in coordination with NASA or ESA intervals. In 2017, Canada picked 2 new astronauts (Joshua Kutryk and Jenni Sidey) out of 3,772 applicants, around the same time NASA announced its 2017 class. Canada hasn’t announced new selections since; as a partner in Artemis, Canada is expected to get seats on lunar missions (indeed, a Canadian – Jeremy Hansen – is on Artemis II). So CSA might do another selection in the coming years to bolster their corps for those missions.

- Others/Emerging: Countries like India (which is preparing its first crewed spaceflight, Gaganyaan) are training astronauts but not through open public selection – India chose Indian Air Force test pilots for its initial astronaut group (four pilots trained in Russia). The UAE and Saudi Arabia have started their own astronaut initiatives recently (e.g., UAE’s Hazza Al Mansouri flew to ISS in 2019, and the UAE has since selected a couple more astronauts who train with NASA; Saudi Arabia sent two astronauts on a private Axiom mission to ISS in 2023, including a female). These efforts often collaborate with either NASA or commercial flight providers.

Comparative Highlights: NASA’s selection stands out for its high volume of applicants and a balanced class optimized for a broad mission portfolio (ISS, Moon, eventual Mars). ESA’s is notable for geographic representation and breaking the disability barrier. China’s emphasizes self-reliance and heavy pilot dominance as it builds a new program. Russia’s seems the smallest and most traditional, constrained by limited program opportunities and less diversity so far. One commonality is that all agencies now stress needing more than just pilots – science and engineering capabilities are valued across the board, reflecting that modern missions (space station research, lunar exploration) require a variety of skill sets.

In terms of international partnerships, NASA’s Artemis program is a catalyst for many of these selections. ESA’s new career astronauts are very likely to fly on Artemis-related missions (ESA provides the Orion service module and in return gets seats on future lunar missions). Japan’s new astronauts explicitly have an eye on the Moon with NASA. Canada’s existing astronauts are integrated into Artemis (one on Artemis II, maybe one on a later Moon landing). So NASA’s 2025 class, while all American, will eventually work side by side with these international colleagues on missions like Gateway (the planned lunar orbit station) and Artemis surface explorations. They’ll train together in many cases and share responsibilities.

It’s also worth noting that unlike NASA, agencies such as ESA and Canada operate on multi-year gaps between selections (due to smaller flight opportunities). NASA’s cadence in recent years has been roughly one class every 4-5 years, which is somewhat more frequent and needed to staff both ISS and Artemis concurrently. China seems to recruit when needed for new program phases (space station, etc.), and Russia’s slowed frequency reflects fewer missions (especially with one Soyuz seat often given to NASA or now to private flyers).

In conclusion, NASA’s 2025 class is part of a global wave of new astronauts entering the scene as humanity pushes beyond low Earth orbit again. While each agency’s process has unique aspects, all are seeking top talent to fulfill their exploration agendas. NASA’s mix of talent and emphasis on diversity and partnerships positions it strongly in this international cohort. And the term “all-American” in NASA’s announcement is a reminder that while NASA leads a coalition, it also sees these astronauts as inheritors of a proud U.S. legacy of space leadership, ready to represent the nation as they work with the world.

Role of Private Space Companies in Shaping Astronaut Careers

The 2025 astronaut class selection vividly illustrates the growing influence of private space companies and public-private partnerships on what it means to be an astronaut today. In several ways, the rise of commercial spaceflight – led by companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, Boeing, and others – is reshaping astronaut career paths and opportunities:

Experience Pipeline from Commercial Space: Two of NASA’s new astronaut candidates come directly from SpaceX, arguably the most prominent commercial space company. Yuri Kubo helped launch dozens of Falcon 9 rockets and managed SpaceX’s avionics projects. Anna Menon not only worked in SpaceX mission control but also flew on a private SpaceX mission (Polaris Dawn) as a crew member. A decade ago, it would have been unheard of for NASA to hire someone who has already been to space on a non-government flight – simply because such flights did not exist. Now, NASA can tap individuals who cut their teeth in the commercial sector, bringing firsthand operational spaceflight experience or unique technical expertise. This demonstrates a new career pathway: one can build a resume in commercial human spaceflight and that can directly serve as a qualification to become a NASA astronaut. It’s a two-way street too: many NASA astronauts who retire go on to work for commercial companies (e.g., former NASA astronauts are leading astronaut training at SpaceX, commanding private missions for Axiom Space, etc.), facilitating knowledge exchange.

Commercial Crew and Vehicles: NASA’s current missions rely on privately-built spacecraft for transporting astronauts. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon (under NASA’s Commercial Crew Program) is now the workhorse ferry to the ISS, and Boeing’s Starliner is expected to join soon. This means NASA astronauts, including the class of 2025 when they start flying, will almost certainly ride on a SpaceX Dragon or similar commercial vehicle for routine missions. Training for these systems is done in partnership with the companies. The influence is such that familiarity with industry practices is a plus – the learning curve for someone like Kubo or Menon on Dragon systems is minimal, since they were already intimately involved. Also, NASA astronauts routinely work with SpaceX engineers during missions; having astronauts who speak the “SpaceX language” internally can improve communication between NASA and its contractors.

Artemis Partnerships: Looking at the Moon program, NASA has contracted SpaceX to build the Human Landing System (HLS) – a version of Starship – to land astronauts on the lunar surface, and recently selected a team led by Blue Origin to develop a second lander. Thus, by the time these 2025 astronauts are eligible for an Artemis Moon mission, they might find themselves training on SpaceX’s Starship or Blue Origin’s lander. Close collaboration with those companies will be required. It’s conceivable that some of these astronauts might even do temporary assignments or internships at companies to help develop the systems (NASA sometimes embeds astronauts with commercial partners as liaisons – e.g., astronauts were involved in testing SpaceX and Boeing capsules). The line between “NASA astronaut” and “commercial astronaut” is getting blurrier: ultimately they’re all astronauts, but with different funding sources or mission profiles.

Private Astronaut Missions: The term “astronaut” itself has expanded. Now we have “private astronauts” – individuals who fly to space not as part of a national corps, but via private missions (like SpaceX’s Inspiration4 or Axiom Space missions to ISS). While NASA’s 2025 class are government astronauts, their careers might intersect with private missions. NASA has started allowing its astronauts to command or join commercial missions (for example, retired NASA astronaut Michael López-Alegría flew as commander of the Axiom-1 private ISS mission, and active NASA astronaut Peggy Whitson, after retiring, led a private mission). In the future, NASA astronauts might be seconded to commercial space station flights or research trips funded by private entities. Conversely, some of these new astronauts could one day leave NASA and become leaders in commercial space ventures – continuing the cycle of cross-pollination.

Training and Facilities: Private companies also contribute facilities and training support. For instance, SpaceX built its own astronaut training simulators for Crew Dragon, which NASA astronauts use. Companies like Blue Origin have astronaut training programs (albeit for suborbital flights currently), and while those are more geared to short tourist flights, they innovate in training techniques that could trickle into broader use. NASA’s T-38 flight training now coexists with some astronauts also training in SpaceX’s simulators. The synergy means a NASA candidate might spend part of their week training with NASA instructors on ISS systems and another part in Hawthorne, CA at SpaceX HQ learning the ins and outs of Dragon software updates.

Inspiration and Recruitment: The success of commercial space missions has broadened public perception of who can go to space. When kids see not only NASA astronauts but also teachers, artists, or wealthy tourists going up on SpaceX or Blue Origin rockets, space starts to feel more accessible. This might encourage more people to pursue STEM careers, and by extension, apply to NASA. NASA’s applicant pools since the commercial crew era have remained very large, suggesting interest is not waning – if anything, the visibility of astronauts has increased due to private sector excitement (think of the media coverage of SpaceX launches or Blue Origin flying William Shatner, etc.). NASA and private companies often reinforce each other’s messaging – for example, the Inspiration4 mission in 2021 explicitly aimed to inspire people to pursue science and raise funds for St. Jude, complementing NASA’s own inspirational Artemis narrative.

Private Space Stations and Post-ISS Plans: NASA is planning to transition from the ISS to commercial space stations in the 2030s. Several U.S. companies (Axiom Space, Northrop Grumman, Sierra Space in partnership with Blue Origin, etc.) are developing orbital outposts with NASA seed funding. By the time the 2025 class has a few missions under their belt, they might find themselves living and working not on a government-owned station, but on a privately-owned orbital facility under NASA contract. They will essentially be NASA crew on commercial platforms. This again underscores why having astronauts familiar with the private sector mindset is valuable. It also means some of them might take on roles in helping design or advise these new stations (astronaut feedback is crucial to designing crew habitats).

Space Tourism and Suborbital Flights: While NASA astronauts don’t participate in suborbital tourist flights, the existence of those flights (Blue Origin’s New Shepard and Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo) has made “astronaut” a more common term. There are now dozens of people who have been to the edge of space via commercial rides. NASA’s stance has been supportive of these as STEM inspiration. Some of the 2025 astronaut candidates may have even been motivated by seeing these developments. Also, NASA sometimes uses suborbital flights for experiments (via programs like NASA’s Flight Opportunities). It’s not far-fetched that a NASA astronaut might coordinate with those programs or even accompany an experiment on a suborbital flight for training (though none have done so yet, the idea has been floated to give astronauts brief space exposure).

In summary, private space companies have become an integral part of an astronaut’s world. NASA’s selection of candidates with direct commercial experience (like SpaceX) signals an embrace of that reality. The Class of 2025 will operate in a realm where NASA missions are carried out with privately-built vehicles, and where their career might involve stints in both government and commercial projects. The traditional image of the astronaut as a strictly government-trained, fighter-pilot type is expanding to include folks who might have started in Silicon Valley or a startup environment. And as spaceflight opportunities increase through commercial means, the overall pie of “astronaut seats” grows – which is good news for those dreaming to fly. NASA’s partnership with private companies is ultimately about getting more people to space more efficiently, and these new astronauts are poised to benefit from and contribute to that partnership, blurring the lines between NASA and commercial astronauts as they all work together in orbit and beyond.

Future Missions and Opportunities: Artemis, ISS, and Mars

The class of 2025 is stepping into NASA at a time of ambitious missions on the horizon. Once they finish training and become eligible for assignments, what might their futures hold? Here’s a look at the missions and programs these new astronauts are likely to support:

International Space Station (ISS): In the near term, some of the new astronauts will undoubtedly serve on the ISS, continuing its legacy of over two decades of continuous human presence in orbit. The ISS is planned to operate until 2030, and with a current rotation of crews via SpaceX Crew Dragon (and hopefully Boeing Starliner soon), NASA needs a steady supply of astronauts for six-month expeditions. By around 2027–2028, members of this class could get assigned as flight engineers on ISS missions, conducting microgravity research, maintaining the station, and performing spacewalks to upgrade systems. They will join international crewmates from Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA, and Canada on these expeditions. These ISS missions will be a crucial training ground – much like how Apollo-era astronauts cut their teeth on Gemini or ISS-era astronauts on Shuttle, doing a stint on ISS gives critical spaceflight experience that would prepare an astronaut for more complex endeavors like a lunar mission. Also, with ISS, NASA is starting to involve private astronauts (Axiom missions), so these NASA rookies might share the station with non-NASA crew at times, learning to work in a more mixed crew setting.

Artemis Moon Missions: The big prize many of them have their eyes on is a chance to go to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis program. Artemis aims to land humans on the lunar surface again and establish a sustainable presence. Artemis II (a crewed lunar flyby) is scheduled for late 2024 with astronauts already selected (from earlier classes). Artemis III, which aims to land on the Moon (currently slated for ~2025 or 2026, though subject to change), will likely use astronauts from the 2013 or 2017 classes for the first landing (including the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, as already announced). However, Artemis is not a one-off – NASA plans Artemis IV, V, VI and so on, roughly one per year, building a long-term lunar exploration program with an orbiting Gateway station and surface habitats.

By the time Artemis IV/V in the late 2020s or early 2030s come around, the 2025 class will be seasoned and could be strong contenders for those crews. For instance, Dr. Lauren Edgar, the geologist, could be a prime candidate to be a lunar surface scientist on one of these missions, given her expertise in planning Moon geology tasks. Likewise, the test pilots in the group (with their proficiency in spacecraft systems) could serve as vehicle commanders or pilot specialists for Orion or the lunar lander. The Artemis missions will often involve docking with the Lunar Gateway (a small space station in lunar orbit) and then descending to the Moon on a lander like SpaceX’s Starship HLS. It’s easy to imagine someone like Adam Fuhrmann or Erin Overcash, with their flight test backgrounds, helping to test new lunar landing vehicles, or someone like Menon overseeing biomedical experiments on how crews live on the Moon’s surface.

Artemis also has an international component – for example, a Canadian is on Artemis II, Europeans and Japanese are likely on later Artemis flights. The 2025 NASA astronauts will work alongside these partners, perhaps in joint training exercises for Gateway or lunar surface operations. By contributing to Artemis, the new class will literally help fulfill humanity’s return to the Moon, advancing goals of setting up a base (Artemis Base Camp) at the lunar south pole, searching for resources like water ice, and learning how to live off the land (in-situ resource utilization). These experiences are explicitly meant to prepare us for Mars.

Mars Missions: Mars is the horizon goal that looms over these selections. NASA’s official stance is that it wants to send humans to Mars, potentially by the late 2030s or 2040s. It’s a long-term aim, but one that informs much of what is being done now (e.g., technology development, Artemis as a proving ground). When Sean Duffy said one of this class might be the first on Mars, it acknowledges that if NASA is able to mount a Mars mission around 2039 or 2041 (just speculating timeline), the crew for that mission would likely be in their 30s or 40s now – which exactly fits the 2025 class profile. For instance, the youngest of the group, Imelda Müller, will be in her mid-40s by the late 2030s, a prime age for such a demanding expedition. Mars missions will be 2-3 year endeavors, requiring crews with a combination of skills: engineering, medicine, scientific research, and the psychological fortitude to endure isolation. When we look at this class, we see those boxes checked – a medical doctor (Müller), engineers (Kubo, Menon), pilot-engineers (nearly all the rest), a geologist (Edgar).

Before a Mars mission happens, these astronauts might also be involved in precursor projects like testing Mars habitat simulations on Earth or month-long missions on the lunar Gateway to simulate the long transit times to Mars, or even participating in year-long ISS missions (NASA has been considering more one-year ISS missions to study human endurance for Mars). By the time of a real Mars mission, those among this class who have excelled and perhaps flown to the Moon could be leading candidates for selection to the Mars crew. It’s speculative for now, but NASA is indeed laying groundwork – for example, they’ve mentioned plans for a Mars transit habitat test around the Moon in the 2030s. The 2025 class could very well populate those early testbeds or even actual deep-space voyages.

New Space Stations – LEO and Lunar: Aside from ISS and Gateway, the 2025 astronauts might also serve on commercial LEO stations later in their careers. NASA’s goal is that by the time ISS retires in 2030, one or more commercial stations will be available for national (and private) use. These might be operated by companies, but NASA astronauts will likely be tenants or even integral crew on them to continue microgravity research. So an astronaut from the 2025 class could spend part of their career living on, say, an Axiom-built station or a Northrop/Blue Origin station as part of NASA’s contracts. This represents a new kind of mission that previous generations didn’t have – essentially being a customer-astronaut on a privately-owned facility. It could involve more interaction with non-NASA personnel, possibly more frequent visiting crews of tourists or international researchers.

Exploration Technology Testing: Many in this class have backgrounds that align with specific future mission needs. For example, the experience of test pilots like Spies, Overcash, Fuhrmann in testing aircraft could translate to testing new spacecraft or rovers. The geologist Edgar will likely be involved in developing science operations for lunar EVAs (she already was doing that for Artemis III geology planning). SpaceX alumnus Kubo, with his launch expertise, might help in integrating and launching new exploration hardware or even in the development of the Starship HLS for the Moon (NASA often assigns astronauts as “vehicle leads” to work with engineers on spacecraft design). Anna Menon’s experience with spacewalks could be tapped when NASA evaluates new EVA suits for the Moon (NASA’s new Artemis spacesuit by Axiom Space is upcoming; having someone who’s done a spacewalk might contribute to its testing or training protocols). The doctor, Müller, might be involved in advancing medical capabilities for deep space – for instance, how to do telemedicine on Mars, or how to handle medical emergencies when return to Earth isn’t quick.

Outreach and Leadership: Beyond missions, these astronauts will also have roles in inspiring and leading. They will likely do a lot of outreach (speaking to schools, representing NASA in public events – something especially important for Artemis as NASA tries to rally public enthusiasm). Later in their careers, some may move into management at NASA, helping to shape mission plans or astronaut office policies (for instance, astronaut Reid Wiseman became Chief of the Astronaut Office; one of these could hold that role in a decade’s time).

The future missions they support will also influence U.S. space policy in return. If Artemis is successful with their help, it will solidify plans for Mars. Conversely, their presence ensures NASA has the human capital to seize mission opportunities. NASA’s human spaceflight roadmap essentially reads: ISS to Artemis to Mars, and this class is poised to touch all three phases:

- Near-term: keep ISS going and transition to private stations.

- Medium-term: help establish a sustainable lunar return (Artemis base, Gateway).

- Long-term: be the pool from which the first Mars crew might be drawn.

To put it dramatically: if one of these 10 is indeed the first human on Mars, that would be one of the greatest “future missions” imaginable – a pinnacle of decades of work. Even if Mars is further out, they are certain to be among the first humans to explore the Moon extensively (beyond Apollo’s brief stays) and set the stage for that next leap.

NASA’s messaging around this class explicitly mentioned these destinations. The press release noted they will support missions to “low Earth orbit, the Moon, and Mars”. It’s no longer just an abstraction – the training includes elements for each of those realms. For example, learning geology is tied to Moon/Mars, and learning about spacecraft systems helps with ISS. NASA, by including Mars in the scope, is signaling that it expects these individuals to be part of multi-decade plans that culminate at Mars.

In conclusion, the future missions awaiting the 2025 astronaut class are diverse and groundbreaking. They will be central to carrying out the Artemis program’s goals of lunar exploration, ensuring a smooth transition from ISS to commercial LEO platforms, and preparing for the dawn of the Mars era. Each member of the class brings talents that align with these missions, from flying next-gen spacecraft to performing science on another world. They truly join at a time when, as NASA leadership said, we’re at the cusp of a “golden age” – one in which humanity’s footprint in space is set to expand dramatically, with the Moon as our immediate frontier and Mars as the next aspirational target. These new astronauts will help turn those plans into reality, one mission at a time.

Broader Impact on U.S. Space Policy and STEM Inspiration

The introduction of a new astronaut class doesn’t just fill NASA’s staffing needs; it also reverberates through American space policy objectives and efforts to inspire the next generation in STEM. The 2025 astronaut class, by its composition and the context of its selection, carries broader significance in these areas:

Sustaining U.S. Leadership in Space: At the policy level, having a robust astronaut corps is a tangible symbol of the United States’ commitment to human spaceflight. It signals to the world that the U.S. is serious about projects like Artemis and beyond. In international forums and diplomacy, NASA astronauts often serve as goodwill ambassadors – the face of American exploration values. By selecting a new class, NASA ensures it has the human capital to staff upcoming missions and demonstrates long-term planning (since these astronauts will serve well into the 2030s). This can bolster confidence among international partners investing in Artemis that the U.S. will see it through (since crewed programs are decades-long endeavors). It also sends a message to strategic competitors (like China) that the U.S. intends to maintain a presence on the new frontier. For instance, NASA Administrator (Acting) Duffy’s framing of the “Golden Age of exploration” and statements about going to Mars can be seen as rallying cries in the ongoing narrative of space leadership.

Alignment with National Space Policy Goals: The Biden Administration (as of 2025) has supported Artemis and has put emphasis on diversity and inclusion in STEM fields. This astronaut class hits both marks: it directly feeds the Artemis program with manpower, and it exemplifies diversity (which aligns with broader policy goals for federal agencies). Recall that in 2021, the White House’s Space Policy Directive embraced the Artemis program and stressed the importance of broad participation. NASA’s selection process – reaching out to underrepresented groups and highlighting role models – is a response to that directive. Members of Congress often pay attention to their districts’ representation in the astronaut corps as well; having folks from various states (Virginia, Texas, Indiana, etc.) fosters nationwide political goodwill towards NASA programs. In fact, when the class was announced, lawmakers from those states tweeted or issued statements congratulating “their” astronaut, which indirectly helps build support for NASA funding in Congress.

STEM Education and Inspiration: NASA astronauts have long been powerful ambassadors for STEM education. Each new class triggers fresh waves of outreach. The diversity of the 2025 class means a wider array of young people can see someone they relate to and think “maybe I can do that too.” For example:

- Seeing a female majority in the class can inspire young girls, who historically might not have envisioned themselves as astronauts due to the male-dominated image of the past. Girls in school now can point to astronauts like Katherine Spies (who’s also a mom and an engineer) or Anna Menon (an engineer and also a working mother during Polaris Dawn) as examples.

- The presence of people of color (though NASA didn’t list ethnicity, some in the group are likely of Asian, Hispanic, or other heritage) also provides representation that matters for minority communities.

- A candidate like Dr. Müller, with a medical background, might spark interest among those in healthcare or biology that there’s a place in space for them too. Likewise, Lauren Edgar’s geology career shows that pure science (not just flying jets) is a pathway to being an astronaut.

- Anna Menon’s path (a private citizen who went to space and then joined NASA) might inspire those in the tech sector or private industry that a NASA career can come even after a non-traditional route.

NASA will surely capitalize on these varied stories in its STEM engagement programs. The astronauts will likely be featured in NASA’s educational materials, make virtual classroom visits, appear on children’s TV shows or podcasts, etc. Historically, whenever NASA has a new class, they are used heavily in outreach during their training period – visiting schools and public events (often virtually these days, or in person if possible). This helps encourage students to pursue STEM courses, as they hear firsthand that the astronauts were once kids interested in science like them. The fact that one of the new astronauts is a former educator or involved in outreach (not sure if any were school teachers, but if not formally, many have done mentoring) will also enhance NASA’s efforts.

Role Models and Public Engagement: The new class is quite media-friendly in the sense that they come with interesting narratives (an astronaut couple, a SpaceX spacewalker, a rugby athlete turned pilot, etc.). These human-interest angles will likely be leveraged to reach audiences beyond the usual space fans. When the public connects personally with astronauts, it tends to sustain support for space initiatives. For example, during the Apollo era, astronauts were household names which helped NASA’s image; today, making these new Artemis-generation astronauts into well-known figures can rally public enthusiasm and, by extension, political support for Artemis and Mars funding. NASA’s decision to have the class do a Reddit AMA immediately is indicative of wanting to build that public connection right away.

Encouraging STEM Workforce Development: Beyond inspiring kids, a new astronaut class can influence young professionals and college students in STEM fields. Knowing that NASA hires people with advanced degrees in engineering, science, medicine, etc., and that even working in commercial space could lead to a NASA role, might incentivize early-career STEM folks to stick with aerospace or research rather than drift to other industries. It feeds the pipeline not just for astronauts but for the broader aerospace workforce. If thousands apply to be astronauts, not all become astronauts, obviously – but many of those thousands are highly skilled individuals who will then perhaps take other important roles (scientists, engineers, technologists). As one quip goes, “NASA’s astronaut rejection letters have done a lot of good for the economy,” meaning those who don’t make it often still contribute mightily in other ways. The competitive nature of selection drives excellence in academia and industry as people strive to meet the bar.

Cultural and Public Support for Space Exploration: Every new class allows NASA to tell a story about why human spaceflight matters. The narrative around this class has been about exploration (“next giant leap”), American leadership, and dreams without limits. That kind of messaging feeds into the public psyche that space exploration is part of American identity and future. It can help maintain positive public opinion, which is crucial when large budgets and projects (like a $4 billion per launch Moon program) need justification. Polls often show strong support for NASA, and iconic astronauts are a big part of that enduring “space nostalgia” and excitement.

Policy Continuity: The timing of this class (2025) is also interesting – it’s after a presidential election year. Regardless of administration changes, NASA’s selection of new astronauts can create a sense of continuity in the human spaceflight program. These astronauts will likely serve through multiple administrations. Their presence can make it harder for any future administration to drastically curtail human spaceflight, because there’s an implicit commitment to use the talent that’s been cultivated. (In the post-Apollo, pre-Shuttle gap of the 1970s, NASA actually paused astronaut selection for 9 years; but since Shuttle, NASA maintained frequent selections, showing a commitment to continuous human spaceflight.)

Diversity and Inclusion Impact: On a societal level, NASA’s high-profile diversity win here can have ripple effects. It shows large organizations can achieve diversity without compromising on talent – which can be an example to other fields (tech, military, academia). In the Wesleyan University commentary on NASA’s recruiting, it was noted that NASA’s astronaut office “looks the way it looks because of intentionality” in addressing biases. That intentionality paying off (with a 60% female class) might encourage other STEM institutions to implement similar strategies. It’s a soft power aspect of NASA as well: demonstrating American values of inclusion and equal opportunity on an international stage (e.g., compare to China’s mostly male cohort or Russia’s all-male recent class, NASA’s class stands out).

Economy and Innovation: While the direct effect is subtle, new astronauts can indirectly spur innovation and economic benefits. For instance, some of the new astronauts might champion or test new technologies (maybe one becomes the test subject for an advanced medical device or a new AI assistant in spacecraft). Their feedback can drive tech development. Astronauts also often work closely with companies developing space hardware – which can accelerate those companies’ products (for example, having an astronaut’s perspective in designing a new rover or habitat can make it more mission-effective, reducing costly mistakes). And when astronauts inspire more students into STEM, that eventually contributes to a skilled workforce that fuels innovation economy-wide, not just in aerospace.

In sum, the 2025 astronaut class serves as a linchpin for both policy and inspiration. They embody the objectives of current U.S. space policy: return to the Moon, push to Mars, do so in an inclusive way, and engage commercial partners. And they become the living links between NASA’s programs and the public that funds them, lighting that spark in young minds and reminding the country of the daring, optimistic spirit of exploration. NASA selecting and celebrating these individuals is more than an HR decision – it’s a statement about the future that the United States envisions: one where Americans (along with international friends) are boldly exploring space, and doing it in a way that brings “all of us” along, reflective of all of America.

The journey of these ten new astronaut candidates is just beginning, but their impact is already being felt here on Earth – in classrooms, communities, and the halls of government – reaffirming why human spaceflight continues to hold such a special place in the American story.

Sources:

- NASA News Release: “NASA Selects All-American 2025 Class of Astronaut Candidates”

- Associated Press (via WTOP): “NASA introduces its newest astronauts: 10 chosen from more than 8,000 applicants”

- Reuters: “Europe names world’s first disabled astronaut” (ESA 2022 class info) reuters.com

- Space.com: “China selects 18 new astronauts…” (China’s 2020 class)

- ITMO News: “Roscosmos… 8 selected out of 420 candidates” (Russia 2018 class)