Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are having a breakout moment—not because humans suddenly have “telepathy,” but because several parallel developments are turning decades of lab research into early clinical reality. In 2025, multiple companies and research groups reported milestones that expand what BCIs can do, how safely they can be tested, and how easily they might plug into everyday technology—from restoring speech and text communication to exploring memory support and faster learning. UNESCO+6Reuters+6Reuters+6

At the same time, regulators and policymakers are racing to define guardrails around “neural data” and mental privacy as neurotechnology moves beyond hospitals. In November 2025, UNESCO adopted what it describes as the first global normative framework on the ethics of neurotechnology, explicitly highlighting both the medical promise of BCIs and the risks of misuse outside tightly regulated clinical settings. Congress.gov+3UNESCO+3The Guardian+3

So what does this mean for cognitive enhancement—a phrase that can sound like science fiction, self-optimization hype, or elite “brain upgrades,” depending on who’s using it?

In practice, the most credible “cognitive enhancement” benefits of BCIs today are about removing bottlenecks between intention and action (especially communication), and about restoring cognitive functions (like memory and attention) in people whose brains or bodies can’t reliably perform those tasks anymore. And that restoration—done well—can look and feel like an enhancement because it increases autonomy, speed, and bandwidth in daily life. UNESCO+4Stanford Medicine+4Nature+4

Below is what BCIs are, what the real benefits look like in 2025, and what needs to happen before “cognitive enhancement” becomes more than a headline.

What a brain-computer interface really is (and why definitions matter)

A brain-computer interface is a system that measures brain activity and translates it into commands for an external device—like a cursor, a keyboard, a speech synthesizer, a robotic limb, or smart-home controls. Most high-performance systems use machine learning models trained to recognize reliable patterns in neural signals. WIRED+3Stanford Medicine+3WIRED+3

BCIs broadly fall into three buckets:

- Invasive implants (inside the skull, on or in brain tissue): high signal quality, surgical risk, and complex long-term reliability challenges. This is where the “highest bandwidth” demonstrations often come from. Reuters+3Nature+3Stanford Medicine+3

- Minimally invasive / endovascular systems (implanted via blood vessels): typically lower surgical burden than open brain surgery and potentially more scalable, but still implantable medical devices. WIRED+1

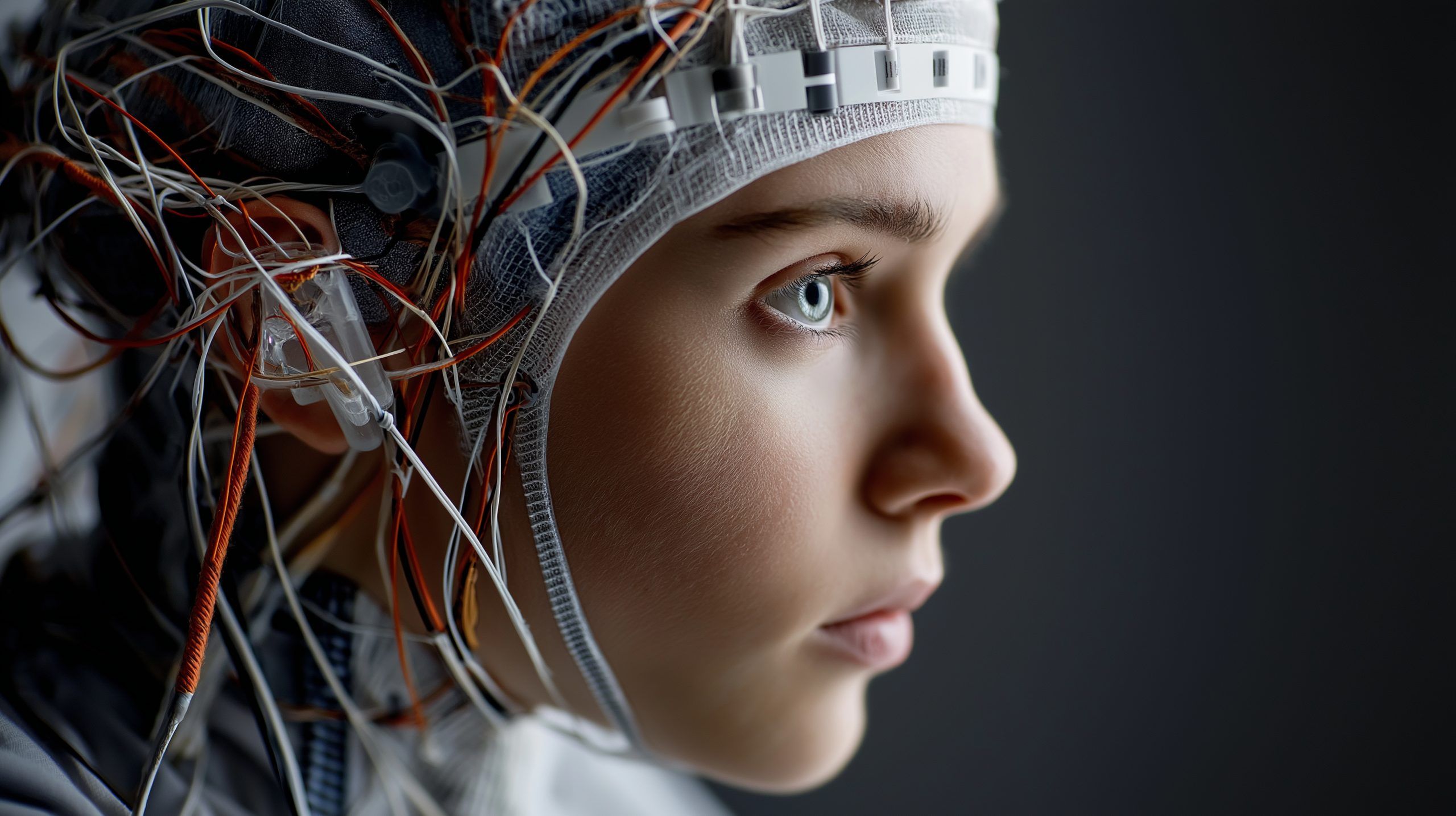

- Noninvasive BCIs (EEG or other sensors on the scalp): safer and easier to deploy, but with lower fidelity and more noise—often better for broad state detection (attention/arousal) than precise, high-speed control. WIRED+1

This matters because the “benefits of BCIs for cognitive enhancement” depend heavily on which type you mean. The benefits—and the risks—are not interchangeable.

A quick roundup of the biggest BCI news shaping the cognitive-enhancement conversation in 2025

These are the developments most directly tied to cognition-related capabilities (communication, language, learning, and real-world device control):

- Neuralink expanded its human implant count: Reuters reported Neuralink said 12 people had received implants as of September 2025, with users collectively logging over 15,000 hours of use. Reuters

- Neuralink moved toward speech-focused applications: Reuters also reported Neuralink planned a clinical trial (announced for October 2025) aimed at helping people with speech impairments convert thoughts into text, and that its device received FDA Breakthrough Device designation for a speech application. Reuters

- Precision Neuroscience got FDA clearance for a cortical interface used in mapping: In April 2025, MedTech Dive reported FDA 510(k) clearance for Precision’s Layer 7 Cortical Interface, an array that can be implanted for up to 30 days for brain activity mapping—important because high-quality neural data is a prerequisite for better decoding algorithms. MedTech Dive

- Paradromics entered long-term clinical trials: Nature reported in November 2025 that the FDA approved Paradromics’ first long-term clinical trial aimed at restoring speech for people with severe motor impairments, beginning with two volunteers. Nature

- Inner-speech decoding advanced in academia: Stanford Medicine reported a 2025 study in Cell exploring “inner speech” decoding (silent, imagined speech) in people with severe impairments—an important step toward faster, less fatiguing communication BCIs and a major flashpoint for mental-privacy debates. Stanford Medicine+1

- Apple moved to support BCI input as an accessibility pathway: Apple’s May 13, 2025 press release described new accessibility features and included support for Brain-Computer Interfaces via Switch Control, and coverage highlighted Apple working with Synchron to enable BCI-based device control. Apple+1

- Synchron showcased AI-assisted, multi-device control: WIRED reported Synchron partnering with Nvidia to improve decoding speed/accuracy and demonstrate thought-driven control across digital and physical environments—pointing toward BCIs that reduce the day-to-day cognitive load of controlling many tools. WIRED

- China accelerated BCI industrial policy and trials: WIRED reported China released a policy roadmap targeting breakthroughs by 2027 and an internationally competitive BCI industry by 2030, spanning medical and consumer uses. Reuters also reported a China-based BCI initiative planning expanded human implants by the end of 2025. WIRED+1

- UNESCO adopted global neurotechnology ethics guidance: UNESCO’s 2025 standard-setting work explicitly calls out both medical promise and mental privacy risks—relevant to any credible discussion of “enhancement.” UNESCO

Now let’s translate those headlines into the actual benefits.

Benefit 1: Faster, less exhausting communication (the most real “cognitive enhancement” today)

If you want the clearest, most meaningful cognitive enhancement benefit BCIs can deliver right now, it’s this:

They can dramatically increase a person’s ability to express thoughts when speech or movement is impaired.

That’s not just convenience. Communication is cognition made visible: turning intentions into language, choices, relationships, work, and agency. When BCIs remove the friction of typing with limited movement, or when they bypass damaged speech pathways, the result can feel like “mental bandwidth” is suddenly restored. Stanford Medicine+2Nature+2

Why “inner speech” is such a big deal

Traditional speech BCIs often decode attempted speech movements—users try to move the muscles used for speaking even if their bodies can’t execute the motion. Stanford’s 2025 work pushes toward decoding inner speech, which could reduce fatigue and potentially increase speed, because users wouldn’t need to “attempt” physical articulation in the same way. Stanford Medicine+1

That said, the same idea triggers obvious privacy fears: if inner speech is decodable, what prevents unintended decoding of private thoughts? Stanford explicitly raised this concern and described software guardrails (such as intentional activation steps) to reduce accidental decoding. Stanford Medicine

BCIs + mainstream devices = practical cognitive leverage

A major shift in 2025 is that BCIs are no longer just “a computer cursor demo.” Apple publicly described support for BCI input via accessibility pathways, and reporting highlighted collaboration with Synchron so implant users can interact with iPhone/iPad-style interfaces using BCI signals rather than relying on indirect emulation tricks. Apple+1

This matters for cognition because the value of communication isn’t only in output speed—it’s also in access to the ecosystem: messaging, calendars, notes, work tools, and the internet. Integration reduces cognitive overhead and makes BCI use more “real life” than “research lab.” The Verge+1

Benefit 2: Memory support and “cognitive prostheses” (restoration first, enhancement later)

The phrase “cognitive enhancement” often conjures healthy people upgrading memory like adding RAM. In 2025, the credible path looks different:

- focus on restoring memory function where it’s impaired,

- prove safety and measurable benefits,

- only then ask what translates to broader enhancement.

Memory prosthesis research is aiming at episodic memory

USC Viterbi described ongoing collaboration on implantable brain prostheses intended to restore episodic memory, particularly when the hippocampus is damaged. The reporting frames this as rebuilding a “broken bridge” in hippocampal circuits—recording upstream activity and stimulating downstream patterns to support memory function. USC Viterbi | School of Engineering

Even if you never implant such a system in healthy people (and today there’s no medical reason to), this line of work supports cognitive enhancement in a broader sense: it demonstrates the principle that closed-loop read/write interfacescould influence cognitive performance in targeted ways. USC Viterbi | School of Engineering+1

Benefit 3: Better learning and attention through closed-loop “electroceuticals”

One of the most interesting cognitive-enhancement angles isn’t typing faster—it’s the idea of BCIs as electroceuticals: devices that modulate brain networks in real time to support cognition when it’s “stuck” or degraded.

Vanderbilt reported a 2025 study (published in Neuron) suggesting that amplifying brief electrical impulses in a cognitive network could improve learning and attention, with a framing that such approaches might eventually support conditions involving memory and cognitive inflexibility. Vanderbilt University

This is important for two reasons:

- It reframes BCIs from “output devices” (control a cursor) to adaptive cognitive systems (support learning processes).

- It emphasizes that the near-term ethical justification is therapeutic: helping people with cognitive disabilities—exactly the kind of “improving lives without jeopardizing rights” balance UNESCO argues for. Vanderbilt University+1

Benefit 4: Independence and reduced cognitive load (cognition isn’t only memory—it’s agency)

A lot of “cognition” is the ongoing, exhausting management of daily tasks—especially when the body can’t cooperate. BCIs can reduce that burden in ways that look like cognitive enhancement:

- controlling a computer without hands

- selecting actions in the physical environment (lights, HVAC, appliances)

- operating assistive or robotic devices

WIRED’s reporting on Synchron describes demonstrations where a user with paralysis can select and control multiple devices in their home environment, and it highlights how improvements in decoding speed and accuracy reduce lag between intention and action—key to making control feel natural rather than mentally draining. WIRED

This is a subtle but real benefit: when control becomes more fluid, people can spend less mental energy “driving the interface” and more on the actual purpose—work, relationships, creativity, rest.

Benefit 5: A pathway to more generalizable BCIs (less training, more usability)

A hidden limiter in many BCIs is training time: collecting labeled neural data and teaching a model what your brain signals mean for your intended commands.

WIRED’s reporting also points to an industry push toward “brain foundation models”—training AI systems on larger datasets across individuals to improve generalization, then fine-tuning for each user. If this works, it could make BCIs:

- faster to set up

- more consistent day to day

- easier to scale beyond a handful of expert labs WIRED

From a cognitive-enhancement perspective, that’s critical. The best interface in the world doesn’t enhance cognition if it’s too fragile, too slow, or too hard to use outside a controlled environment.

The uncomfortable truth: “Enhancement” for healthy people isn’t the main story—yet

A responsible take on cognitive enhancement has to say this plainly:

Most of the meaningful, evidence-backed benefits in 2025 are therapeutic—aimed at restoring function for people with paralysis, ALS, stroke, epilepsy-related impairments, and other serious conditions.UNESCO+4Reuters+4Nature+4

That doesn’t make the benefits smaller. It makes them more real.

Widespread elective enhancement (healthy people getting implants for productivity, memory, or “AI brain upgrades”) runs into hard barriers:

- surgical risk vs. marginal benefit

- long-term biocompatibility and maintenance

- security and privacy threats

- ethical concerns about coercion (workplaces, schools, militaries)

- fairness and access

UNESCO’s neurotechnology ethics framework explicitly warns that neurotechnology is often strictly regulated medically but can be under-regulated elsewhere, and it flags risks around mental privacy and vulnerable populations (including children) in non-therapeutic contexts. UNESCO

The risks that come with the benefits (and why governance is now part of the BCI story)

If BCIs can increase cognitive capability, they also create new categories of harm—some familiar (data privacy), some unique (mental privacy and autonomy).

1) Mental privacy and “neural data”

As neurotechnology expands, policymakers are increasingly treating neural data as uniquely sensitive. A Future of Privacy Forum analysis noted that, as of mid-2025, multiple U.S. states had enacted laws addressing “neural data” or “neurotechnology data,” reflecting rising concern about how brain-related signals could reveal mental states. Future of Privacy Forum

At the federal level, the text of the “MIND Act of 2025” proposes directing the FTC to study governance of neural data, underscoring that regulation is still emerging and definitions vary. Congress.gov

2) Autonomy: Who is in control—the user, or the model?

As BCIs become more AI-driven (predicting context, offering suggestions, smoothing noisy signals), the line between “user intent” and “system inference” matters. WIRED’s Synchron coverage explicitly raises concerns about how AI could shift from decoding intended commands to predicting desires—and why override mechanisms matter. WIRED

3) Safety, reliability, and the long game of implants

FDA milestones like Precision Neuroscience’s mapping-focused clearance matter because they build a bridge from experimental devices to regulated clinical use—but they also highlight that much of today’s progress is still early-stage, incremental, and medically scoped. MedTech Dive

What to watch next: the next 12–24 months of cognitive enhancement via BCIs

If you’re tracking BCIs specifically for cognitive enhancement benefits, these are the signals that matter more than flashy demos:

- Speech restoration trials and results (speed, accuracy, fatigue, real-world usability) Nature+2Reuters+2

- Generalizable decoding (less per-user training; more robust performance across environments) WIRED

- Integration with mainstream ecosystems (accessibility protocols, interoperability, safe APIs) Apple+1

- Closed-loop cognitive therapeutics (evidence that stimulation can reliably improve memory/attention outcomes, not just correlate with them) Vanderbilt University+1

- Governance that keeps pace (clear definitions of neural data, consent requirements, restrictions on coercive use) UNESCO+2Future of Privacy Forum+2

And globally, watch industrial roadmaps that explicitly blend medical and consumer ambitions—like China’s stated plan to pursue breakthroughs by 2027 and industry competitiveness by 2030, which could shape both innovation speed and regulatory norms. WIRED+1

Bottom line: The real “cognitive enhancement” is emerging—starting with restoration, not superpowers

The strongest benefits of brain-computer interfaces for cognitive enhancement in 2025 are not about turning people into geniuses. They’re about unlocking cognition that’s already there—letting someone communicate at the speed of thought (or closer to it), control tools without exhausting workarounds, and potentially restore memory and learning functions when disease or injury breaks the brain’s normal pathways. UNESCO+5Stanford Medicine+5Nature+5

If the field succeeds, the next era of enhancement won’t be a single device or company. It will be an ecosystem: safer hardware, smarter decoding, mainstream interoperability, and governance that protects mental privacy while expanding access to life-changing capabilities.