- Rare double comet spectacle: In October 2025, two newly discovered comets – C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) and C/2025 R2 (SWAN) – are gracing the night sky at the same time en.wikipedia.org. Both icy visitors hail from the far reaches of the solar system and offer a unique back-to-back skywatching opportunity.

- Comet Lemmon’s bright promise: Discovered in January 2025, Comet C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) has brightened rapidly and could reach around magnitude 4 (or even brighter) by late October, making it faintly visible to the naked eye under dark skies earthsky.org wral.com. It will be closest to Earth on October 21, 2025, passing tens of millions of miles away (roughly ~50 million miles) space.com 1 .

- Comet SWAN’s close approach: Comet C/2025 R2 (SWAN), discovered in September 2025 via NASA’s SOHO space observatory, survived its swing around the sun in mid-September. It will make its closest pass by Earth around October 20, 2025 at about 25 million miles distance space.com. SWAN is expected to peak near magnitude 6 – on the cusp of naked-eye visibility – meaning binoculars will likely be needed to spot its fuzzy glow space.com 2 .

- When and where to look: Northern Hemisphere observers get the best view of Comet Lemmon, which appears in the northwest sky after sunset by mid-to-late October earthsky.org earthsky.org. Comet SWAN starts out low in the western evening sky (favored for Southern Hemisphere early on) and gradually climbs higher each night; by late October it will be about 30° above the horizon after dusk for mid-northern latitudes space.com space.com. Finding a dark site away from city lights is crucial – both comets will appear as diffuse, dim “ghosts” in the sky rather than bright stars wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl 3 .

- Cosmic coincidence: Seeing two comets at once is a rare treat. Astronomers note that Comet Lemmon could glow around magnitude 2–4 just as Comet SWAN reaches mag 4–6 in the same week of late October en.wikipedia.org. This unusual double show coincides with the Orionid meteor shower (peaking October 21–22), so stargazers might catch shooting stars from Halley’s Comet while hunting these cometary visitors 4 .

- Comets 101 – expect surprises: Comets are often called “dirty snowballs” – primordial leftovers of ice and dust from the solar system’s birth that sprout glowing comas and tails when warmed by the sun fox8live.com fox8live.com. They originate in distant reservoirs like the Oort Cloud far beyond Pluto fox8live.com. Both Lemmon and SWAN are long-period comets on thousand-year orbits making once-in-a-lifetime visits to our skies en.wikipedia.org space.com. But they can be unpredictable – as comet expert David H. Levy quips, “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and they do precisely what they want” wral.com. In other words, brightness forecasts can change without warning, so be prepared for surprises!

Two Icy Visitors from the Outer Solar System

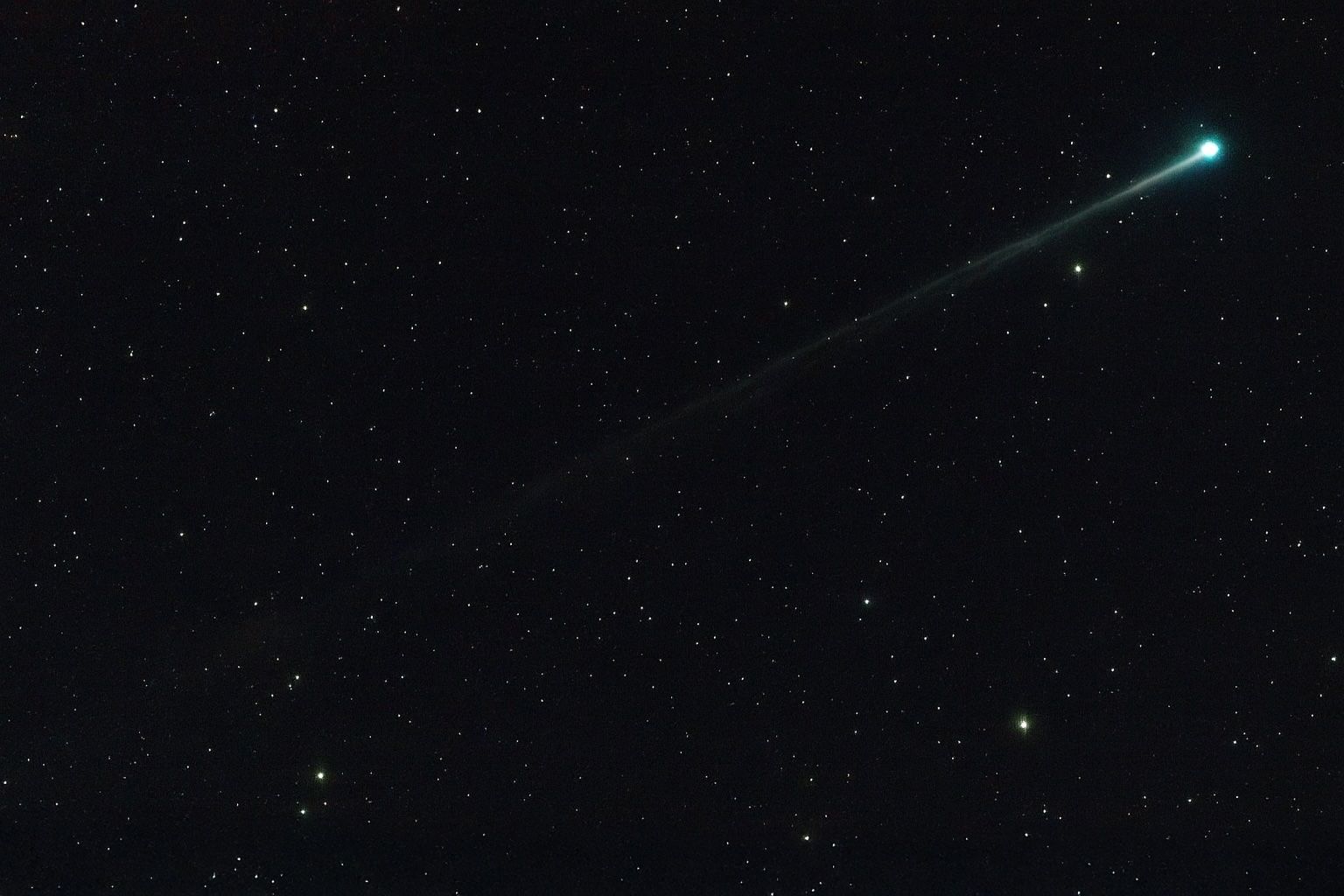

This fall’s night sky brings not one but two comets into view – a rare cosmic coincidence that has amateur astronomers buzzing. Comet C/2025 A6 (nicknamed Lemmon) and Comet C/2025 R2 (SWAN) both formed in the frigid outskirts of the solar system and have traveled inward for the first time in millennia. “These features make ‘Lemmon’ a striking reminder of the icy wanderers that visit the inner solar system from the distant Oort Cloud,” noted astronomer Aleix Roig after capturing the comet’s eerie green glow in late September space.com. Comets like these spend most of their lives in the Oort Cloud (a realm of frozen bodies on the chilly fringes of our solar system), until gravitational nudges send them sunward. As they approach the sun, solar heat causes them to outgas, releasing dust and gas that form a fuzzy coma and often two tails – one of dust and one of ionized gas fox8live.com fox8live.com. The specific gases can even tint a comet’s coma; for example, diatomic carbon gas fluorescing in sunlight gives many comets a greenish coma 5 .

Both Comet Lemmon and Comet SWAN were discovered just this year (2025), adding to the excitement. Their names reflect how they were found: Comet Lemmon was first spotted by the Mount Lemmon Survey’s telescope in Arizona, and Comet SWAN was detected in imagery from SOHO’s Solar Wind Anisotropies (SWAN) camera fox8live.com. Each comet is on a very elongated orbit that takes it far beyond the planets – Comet Lemmon’s path around the sun spans roughly ~1,300 years en.wikipedia.org, while Comet SWAN’s orbit is on the order of 1,000–1,400 years space.com space.com. In effect, no one alive has ever seen these comets before, and once they depart, they won’t return for many centuries. That makes their joint appearance in October 2025 truly special.

What are the chances of two comets being visible simultaneously? In recent history it’s uncommon to have two potentially observable comets in the same month. Yet by late October 2025, Comet Lemmon and Comet SWAN are indeed sharing the sky, each reaching peak brightness within days of each other en.wikipedia.org. This “two-for-one” comet show is drawing comparisons to summer 2020, when Comet NEOWISE delighted skywatchers – except this time, we get a double feature. While neither Lemmon nor SWAN is expected to become as brilliant as 2020’s Comet NEOWISE, having two comets at once offers twice the opportunity for observers (and astrophotographers) to catch a glimpse of these ghostly green visitors. And because comets are notoriously capricious, astronomers are eager to see if one of these might flare in brightness or develop an impressive tail. As David Levy cautioned, “comets…do precisely what they want” wral.com – so both comets bear careful watching as the month unfolds.

Adding to the cosmic coincidence, October 2025 brings other sky highlights. Around the same time the comets reach peak visibility, Earth will pass through Halley’s Comet’s debris stream – producing the Orionid meteor shower that peaks on the night of October 21–22 wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl. That means intrepid stargazers could see Comet Lemmon shining in the west and catch Orionid “shooting stars” streaking from the east, all under the same moonless late-October sky. There’s even an interstellar interloper in the mix: astronomers in 2025 also discovered Comet 3I/ATLAS, only the third known object arriving from outside our solar system earthsky.org earthsky.org. It’s very faint (visible only in large telescopes) and on a trajectory taking it near the sun in late October. While 3I/ATLAS isn’t something the public can easily see, its presence underscores what a remarkable time this is for comet lovers – truly, as one science publication proclaimed, “October 2025 is a great month for comets!” 6 .

Meet Comet C/2025 A6 (Lemmon)

Comet C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) is shaping up to be the brightest comet of the year. It was discovered on January 3, 2025 by astronomers using the 60-inch telescope at Mt. Lemmon Observatory in Arizona en.wikipedia.org. The “A6” in its designation indicates it was the 6th comet found in the first half of January 2025. Images later revealed the comet had actually been captured (unrecognized) in survey photos as far back as November 2024 earthsky.org. Armed with these data, astronomers calculated Comet Lemmon’s extremely long orbit – it likely last visited the inner solar system around the 7th century AD en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org! In inbound orbit it took ~1,350 years to loop around the sun, and after this swing-by (slightly altered by the planets’ gravity) it will take roughly 1,150 years to return en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org. In other words, this is a once-in-a-millennium comet for skywatchers on Earth.

Fortunately for us, Comet Lemmon appears to be living up to expectations so far. At discovery it was an extremely faint magnitude +21, but by early October it had surged to about magnitude +7 space.com space.com – a 100,000-fold increase in brightness – and continues to brighten. By mid-October, observers reported it near the threshold of naked-eye visibility under dark skies (around mag 6) and easily visible with binoculars as a fuzzy star-like spot earthsky.org earthsky.org. The comet will make its closest approach to Earth on October 21, 2025, coming a little over 55 million miles (89 million km) from us space.com space.com. Around that time and into late October, Comet Lemmon is forecast to reach its peak brilliance. Various estimates put its maximum brightness anywhere from about magnitude 4 (comparable to a dim star in the Big Dipper) to as high as magnitude 2.5 earthsky.org. If it achieves the upper end of that range, it could be faintly visible to the unaided eye even by casual observers – though only in very dark, clear conditions. Even at the lower end (~mag 4–5), it should be detectable with basic binoculars or a small telescope quite easily 7 .

Where and when can you see Comet Lemmon? This comet favors the Northern Hemisphere, as it spends October moving through northern constellations. In early October, Lemmon was lurking in the morning sky – skimming the horizon under the Big Dipper in Ursa Major just before dawn earthsky.org. It was so low and faint then that only dedicated observers with telescopes could pick it out (around mag 7 at that point earthsky.org). But things improve as the month goes on. “By mid-October, the comet will become easier to see, rising in the evening sky,” EarthSky’s Kelly Kizer Whitt reports earthsky.org. Indeed, around October 16, Comet Lemmon transitions into a convenient post-sunset object. On that date it passes near the star Cor Caroli in the constellation Canes Venatici earthsky.org earthsky.org, potentially glowing just on the verge of naked-eye visibility. After that, the comet climbs higher in the sky each evening. During the final week of October, Lemmon will be trekking from the western sky toward the southwest after dusk. It crosses in front of the constellation Ophiuchus around Halloween earthsky.org earthsky.org. The timing is perfect: a nearly new Moon at the end of October ensures dark skies, and Comet Lemmon is likely to be at its brightest. Observers with clear weather might look for a faint smudge of light low in the west in the hour or two after sunset. Under ideal conditions (and if the comet performs as hoped), you could even just barely make it out with the naked eye from a rural dark-sky site earthsky.org earthsky.org. More likely, binoculars will reveal it as a small, diffuse glow. Long-exposure photos should easily capture its presence and perhaps a tail.

Speaking of tails, astrophotographers around the world have been training their lenses on Comet Lemmon as it brightens. Images in September and early October show a beautiful, turquoise-green coma and a growing ion tail. The green hue is a common sight in comet photography – it comes from carbon-based gases (like C<sub>2</sub>) in the coma that glow green when energized by ultraviolet sunlight space.com. Comet Lemmon’s tail, meanwhile, has been changing day by day as solar wind shapes it. Veteran comet photographer Dan Bartlett documented the comet’s twisting ion tail over several nights in California, showing it “wax and wane” as it was buffeted by solar wind space.com space.com. By October, the tail extended several degrees (many times the width of the full moon) in long-exposure shots space.com space.com. Visually through binoculars, don’t expect such drama – most observers see only a condensed bright head (the nucleus and surrounding coma) and perhaps a faint streak of a tail a degree or two long in ideal conditions space.com. Still, the presence of a tail confirms you’re looking at a comet, not a fuzzy star or galaxy. “In this image, you can clearly see the comet’s greenish coma… and its developing tail extending away from the Sun,” wrote Aleix Roig of a photograph he took on September 22 in Spain space.com. He and others describe Comet Lemmon as a “spectacular” sight in long exposures, and an enticing target for anyone with a camera and tracking mount.

Crucially, Comet Lemmon’s behavior so far has matched astronomers’ predictions closely wral.com. That consistency gives hope that it will continue brightening on schedule. But because “comets are like cats…they do precisely what they want” wral.com, one should be prepared for anything. Comet Lemmon could fizzle out early or surprise us with an outburst. The good news: as of the first week of October, observers in the Southern Hemisphere had already reported the comet “steadily brightening” and reaching the edge of naked-eye visibility under dark skies wral.com wral.com. This builds confidence that Comet Lemmon really will turn into a subtle naked-eye object for at least some observers by late October wral.com. If so, it might become the brightest comet since NEOWISE (2020) for Northern Hemisphere stargazers. Even if it stays a binocular object, Comet Lemmon is likely to be the more photogenic of the two October comets, thanks to its anticipated higher brightness and favorable positioning in a dark evening sky after moonset.

Meet Comet C/2025 R2 (SWAN)

Hot on Lemmon’s heels is Comet C/2025 R2 (SWAN) – a comet that practically announced itself out of nowhere in September 2025. This comet’s discovery story is a thoroughly modern one. On September 10, 2025, amateur astronomer Vladimir Bezugly in Dnipro, Ukraine was poring over publicly available images from the SOHO spacecraft’s SWAN instrument (which monitors hydrogen gas emissions across the sky). In the data from early September, he noticed a “bright blob” moving against the background of stars near the Sun space.com space.com. That blob turned out to be a previously unknown comet – and a relatively bright one at that. “In my memory, this is one of the brightest comet discoveries ever made on SWAN imagery,” Bezugly marveled, noting it was the 20th comet found via SWAN so far space.com. Within days, other observers (especially in the Southern Hemisphere) started spotting the object in their own photos, confirming the find. The new comet was officially designated C/2025 R2 and informally named SWAN after the instrument that detected it space.com 8 .

Comet SWAN reached its perihelion (closest point to the sun) on September 12, 2025, at about 0.5 AU from the Sun (inside the orbit of Venus) space.com space.com. Having survived that solar encounter, it then headed toward Earth’s vicinity, though not too close – its trajectory will miss Earth by a comfortable margin. According to calculations, Comet SWAN will come closest to our planet on October 20–21, 2025, at roughly 25 million miles away (around 40 million km) space.com. That is about 0.27 AU, well outside the Moon’s orbit, so there is no danger – only a chance for some prime comet viewing. Notably, SWAN’s orbital eccentricity is extremely high (about 0.996), indicating a very long period. Early estimates suggested an orbital period around 1,400 years space.com. It may even be on a one-time trajectory from the Oort Cloud (some initial estimates had suggested tens of thousands of years, essentially a first and only visit) earthsky.org. In any case, like Comet Lemmon, this comet will not return in our lifetimes. It’s truly a “once-in-a-lifetime” celestial visitor.

When first discovered in mid-September, Comet SWAN was about magnitude +7 to +8 – just below naked-eye level, but visible in binoculars as a tiny smudge space.com space.com. Interestingly, in late September the comet underwent a brief outburst, brightening to around mag 5.9 en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org. This raised hopes that it might become visible to the naked eye, at least from dark sites. As of early October, Comet SWAN was reported around magnitude 6 to 6.5 en.wikipedia.org space.com, right at the edge of human visual detection under ideal conditions (magnitude 6–6.5 is often cited as the cutoff for unaided eyes in a dark sky space.com). Experienced observers with good binoculars have described SWAN as a small, condensed coma with a faint tail about 1–2 degrees long space.com space.com. In photographs, SWAN shows off a beautiful blue-green coma (typical for gas-rich comets) and a thin ion tail. One striking image from mid-September captured Comet SWAN near the bright star Spica, the comet’s tail appearing as a subtle streak next to the star’s glare space.com 9 .

The big challenge with Comet SWAN has been its position in the sky. For much of September, it lurked too close to the Sun’s direction to be readily seen, especially from northern latitudes space.com. Southern Hemisphere observers had a bit better view, as the comet appeared in their evening sky after sunset, albeit low. As October progresses, SWAN’s geometry improves for the Northern Hemisphere. The comet is moving on a northerly path, meaning each day it appears a little higher after sunset for observers in mid-northern latitudes space.com space.com. In the first week of October, SWAN was still very low in twilight from the U.S. and Europe – only ~10–15° above the western horizon at dusk space.com. By mid-October, it should become easier to pick up in the southwest sky as darkness falls, perhaps ~20° high. By October 25–28, just after its closest approach, Comet SWAN will stand much higher – on the order of 25–30° above the horizon at the end of evening twilight, and staying up for a few hours into the night space.com space.com. Essentially, late October is the window when both hemispheres have a shot at seeing this comet in a dark sky.

How bright will Comet SWAN get? This has been a matter of some debate and cautious optimism among comet watchers. Forecasts from experienced comet observers (like Seiichi Yoshida and Gideon van Buitenen) suggest a peak brightness between magnitude +6 and +7 during the third week of October space.com space.com. That would put it right at naked-eye threshold. Some predictions even allow that SWAN might nudge slightly brighter (mag 5.5 or 5.0 in a best-case scenario). Daniel Green of the IAU’s comet bureau projected the comet hovering around mag 6 through early October, perhaps briefly brightening by a few tenths of a magnitude around October 12 space.com space.com. Indeed, that mid-September outburst to mag 5.9 might have been the hinted bump in brightness. If SWAN can sustain mag ~6 into late October, it means from a dark rural location one might barely glimpse it without optics – essentially a soft glow at the edge of vision. In suburban or light-polluted settings, binoculars will definitely be required space.com space.com. And even with binoculars, don’t expect a dramatic sight – Comet SWAN is a diffuse gas ball, not a high-contrast object. “Remember, you’re not looking for a sharp star-like object, but rather something spreading its light out over a comparatively large area,” veteran sky columnist Joe Rao reminds prospective observers space.com. SWAN’s lack of abundant dust means it may appear fainter than equally bright (in magnitude) dusty comets, since gas glows with a dimmer, bluish light space.com 10 .

One thing we won’t get from Comet SWAN is a meteor shower – a rumor that circulated due to the Earth seemingly crossing SWAN’s orbit in early October. In reality, the comet’s path is tilted out of the plane of Earth’s orbit by millions of miles, so no meteors from SWAN will hit Earth space.com space.com. (The Orionid meteors this month come from an entirely different comet, Halley’s Comet, and are a known annual shower.) What Comet SWAN will provide is the novelty of seeing a brand new comet make its sole appearance in our lifetimes. This comet was only just discovered weeks ago, and each day we are literally watching it evolve. Interestingly, during late September, Comet SWAN appeared in the same patch of sky as the interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS, allowing at least one photographer to capture two comets in one frame earthsky.org earthsky.org. The interstellar comet was a tiny speck next to SWAN’s green coma – a reminder of how special it is when a comet becomes bright enough for us to see at all without huge telescopes.

By early November 2025, Comet SWAN will fade and recede, on its way back into the depths of space. But for a few weeks in October, it offers a chance for determined skywatchers to spot a distant, ghostly traveler with their own eyes – and to do so alongside another comet in the sky at the same time. As one astronomy writer put it: “October 2025 is a great month for comets!” 6 .

How to See the Comet Double Feature

Viewing comets requires a bit of planning, but the payoff is witnessing a rare celestial spectacle. Here are tips and timings to help you catch Comet Lemmon and Comet SWAN during their October showing:

- Find dark skies: Both comets are relatively faint, so observing from a location with minimal light pollution is essential wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl. Get away from city lights – the darker the sky, the better. Under a clear, moonless dark sky, you stand the best chance of seeing the comets as subtle glows. In a city or bright suburb, it will be very difficult to spot them without a telescope.

- Use binoculars or a telescope: While Comet Lemmon might become visible to the naked eye at its peak, bring binoculars to be safe. A decent pair (7×50 or 10×50, for example) will greatly enhance your ability to find these objects wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl. Through binoculars, the comets will appear as fuzzy, star-like patches of light. A small telescope (or even a camera with a long exposure) can reveal more detail, like a hint of a tail.

- Know where and when to look: For Comet Lemmon, the key time is late October. By about October 16 and onward, start scanning the western to northwestern sky after sunset. Shortly after the Sun sets, as soon as the sky grows dark, look low above the horizon in that direction. Lemmon will climb a bit higher each day; around Oct. 20–25 it should be roughly 15–30° above the horizon at nightfall (with 10° being about the width of your fist at arm’s length) space.com space.com. Notably, on Oct. 21 Lemmon will be about 42° away from the Sun in the sky en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org – far enough to be seen in a dark sky. If you have a star chart, you can locate reference stars: in late October, Comet Lemmon moves from Boötes into Ophiuchus, roughly west of the bright star Arcturus in the early evening earthsky.org. It will set a few hours after the Sun by month’s end. For Comet SWAN, start looking mid-October onward. Initially it will lurk low in the southwest after sunset. Each day, it appears slightly higher and a bit further south. By Oct. 25, SWAN should be about “three fists” (≈30°) above the south-southwest horizon at the end of twilight space.com space.com, and it won’t set until after midnight. SWAN travels across the constellations Libra, Scorpius, Ophiuchus, Serpens, and Sagittarius during October space.com – a path that keeps it in the general southwest sector of the sky during evenings. If you’re in the Southern Hemisphere, you likely had the best view earlier, but by late October SWAN also becomes accessible to northerners as described. Timing tip: Try to observe on moonless nights – around October 10–12 (waning crescent) or after October 24 (when the Moon is new on Oct. 31). A bright Moon will wash out these faint fuzzies.

- Be patient and sweep the sky: Comets don’t pinpoint like stars; they’re more like dim cotton balls against the sky. When using binoculars, slowly sweep the target area. Look for any “star” that doesn’t quite focus to a point – that could be the comet’s diffuse coma. It may help to use averted vision (looking slightly to the side of the object) to detect the faint glow. If you have access to one, an astronomy app or star chart showing the comet’s position on the date of your observation can be invaluable 11 .

- Watch during Orionids meteor shower: Mark your calendar for the night of Oct 21/22, when the Orionid meteor shower peaks. This could be an ideal session: Comet Lemmon will be near its closest and brightest on the 21st en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org, Comet SWAN will be reaching its closest on the 20th–21st space.com, and with the Orionids you might catch bright meteors streaking across the sky every few minutes. The meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Orion (rising late evening), but they will be visible all over the sky. So while you’re scanning for comets in the west or southwest, you might also see a few meteors flash by – a bonus treat 4 .

- Photography: If you have a DSLR or mirrorless camera and a tripod, try taking long-exposure shots of the area of the sky where the comet is. Even a 10-20 second exposure (with high ISO and a wide lens) might capture the comet’s faint light, revealing it in images even if your eyes can’t quite see it. Many of the stunning comet photos you see are long exposures that reveal more of the tail and coma than is visible in real time.

Finally, manage expectations and enjoy the experience. These comets are not expected to blaze dramatically like a “Great Comet” lighting up the whole sky. They will be subtle and require some effort to find. But there is something profound about spotting a comet – realizing you are seeing a primordial chunk of ice from the solar system’s edge, possibly visiting for the first time. And in this case, you’ll be seeing two such ancient visitors at once, an exceedingly rare occurrence en.wikipedia.org. Even seasoned astronomers are excited: “Two comets are moving into your night skies in October,” as one headline trumpeted, emphasizing the unique chance to witness a double comet show.

A Rare Cosmic Double Feature – Don’t Miss It

In the annals of skywatching, 2025’s October comet bonanza will stand out. It’s not every year – or even every decade – that two comets discovered just months prior end up visible together in the sky. Comet Lemmon and Comet SWAN are both refugees from the solar system’s deep freeze, now catching the sunlight and putting on their modest displays for Earth. Each has its own story: one found by an automated survey in Arizona, the other by a vigilant amateur scanning satellite images fox8live.com space.com. Each has traveled for centuries (if not longer) to reach us this fall. And by sheer coincidence of orbital mechanics, both are peaking in brightness virtually side-by-side in time 12 .

For the public, this is a wonderful reminder of why we look up. You might have to work a little – find a dark spot, bring binoculars, and patiently search – but the reward is seeing something truly otherworldly. A comet in the night sky has an almost mystical quality; unlike the steady stars or planets, it appears as a hazy, glowing ember that wasn’t there before and soon will be gone. Now we have two of these apparitions at once. As EarthSky’s editors put it, October 2025 is a great month for comets, and possibly one of the most spectacular months for sky observers in years wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl 13 .

If you step out on a crisp clear night this month, you might catch Comet Lemmon low in the west, a faint beacon from 49 million miles away en.wikipedia.org space.com. Swing your gaze a bit southward, and you might find Comet SWAN, that tenuous patch of light marking a voyager from the Oort Cloud as it heads back into the darkness. Don’t be discouraged if at first you see nothing – let your eyes adjust, consult a star map, and try again on another night. Comets sometimes require perseverance. But consider what you’re witnessing: two primordial snowballs, formed at the dawn of the solar system, now unraveling gently under the sun’s warmth and painting our sky with their ephemeral glow. It’s the kind of experience that connects us to the rhythms of the cosmos.

And if clouds or life’s obligations thwart you this time, take heart that science is always finding new wonders. In fact, hot on the heels of Lemmon and SWAN, another comet – C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) – is on the horizon for late fall fox8live.com. It’s uncertain if that one will become visible, but 2025 clearly has no shortage of cosmic visitors. For now, though, the spotlight is on Comet Lemmon and Comet SWAN. They invite us to step outside, look upward, and ponder the vast orbital dance that has delivered a double dose of cometary beauty to our night skies. Don’t miss the show – opportunities like this come once in a lifetime (or maybe two, if you’re very lucky) wral.com 14 .

Sources: Marina Koren, The New York Times (Oct. 3, 2025) en.wikipedia.org; Eddie Irizarry & Kelly K. Whitt, EarthSky earthsky.org earthsky.org; Joe Rao, Space.com space.com space.com; Tony Rice, WRAL News wral.com wral.com; Amber Wheeler, Fox8 News fox8live.com fox8live.com; Marek Świdrak, Wągrowiec Portal wagrowiec-wydarzeniazostatniejchwili.pl 4 .