On December 12, 2025, the rare interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS (also written 3I/Atlas) is back in headlines for two reasons: a newly released X‑ray view from ESA’s XMM‑Newton and fresh Gemini North telescope images showing the comet looking noticeably greener—all as the object heads toward its closest approach to Earth on December 19(still very far away, and not a threat). NASA Science+3European Space Agency+3Phys.…

What’s new today: 3I/ATLAS shines in X‑rays and shifts greener in visible light

Today’s (12/12/2025) coverage converges on a simple theme: as 3I/ATLAS moves away from the Sun, scientists are catching it in more wavelengths—and the comet’s behavior is evolving quickly enough to be visible even in week‑to‑week comparisons.

Today’s key developments include:

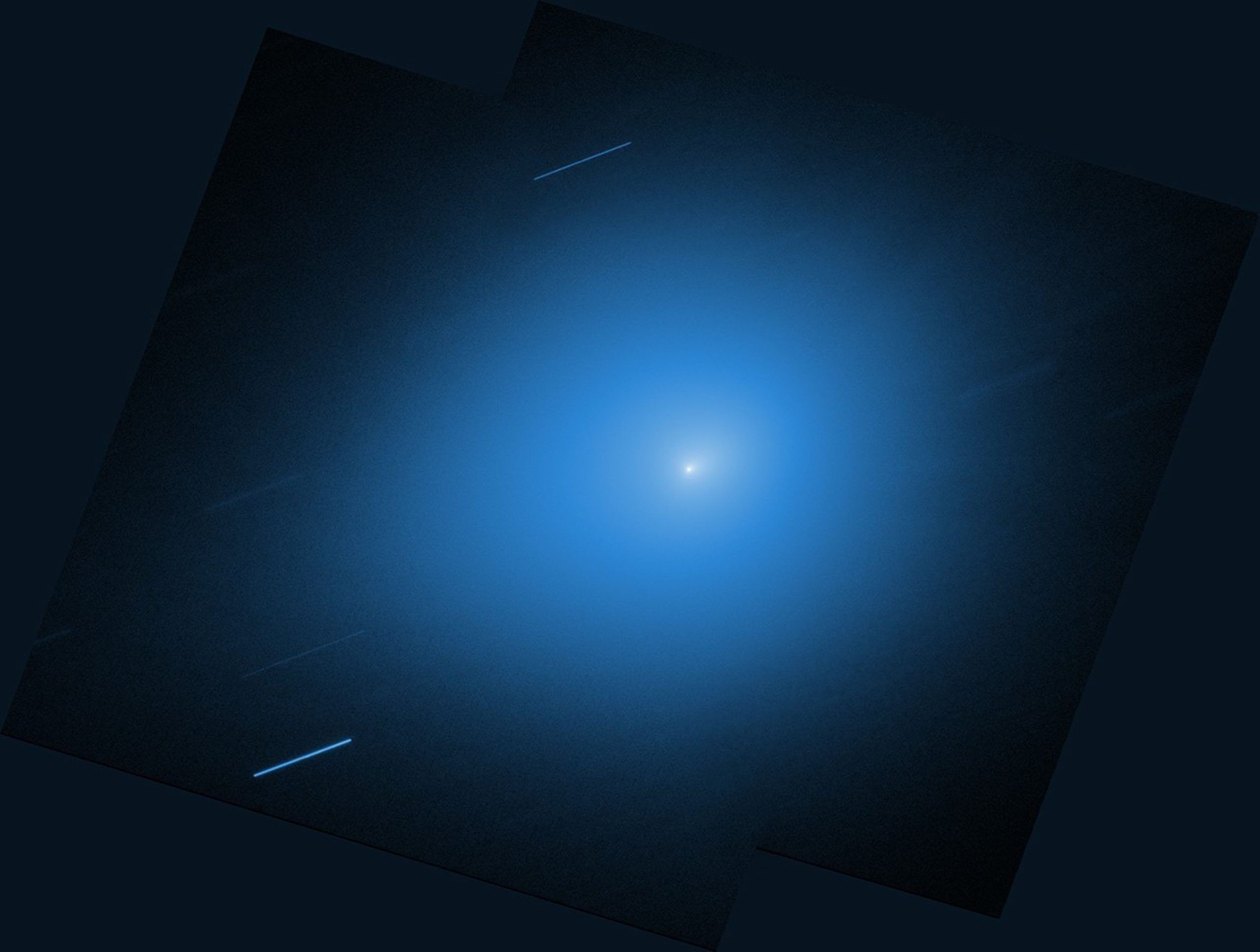

- ESA released an X‑ray image showing 3I/ATLAS glowing in low‑energy X‑rays after a long observation by XMM‑Newton. European Space Agency

- Gemini North released new color imagery (taken Nov. 26) indicating the coma now has a faint greenish glow—a sign the comet is venting gas species that emit at green wavelengths. Phys.org+1

- Multiple outlets also emphasize that the best geometry for observers happens around Dec. 19, when 3I/ATLAS reaches its minimum distance from Earth—yet remains far beyond the Moon, and even beyond the Sun–Earth distance. NASA Science+2NASA Science+2

ESA’s XMM‑Newton captures comet 3I/ATLAS in X‑ray light—and it’s more than a pretty detection

The most distinctive “new” item dated December 12 is ESA’s announcement that the XMM‑Newton X‑ray space observatory observed interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS on December 3 for about 20 hours, when the comet was roughly 282–285 million kilometers from the spacecraft. ESA says XMM‑Newton used its EPIC‑pn camera, its most sensitive X‑ray imager. European Space Agency

Why do comets glow in X‑rays at all?

ESA explains that astronomers expected the glow: when gas streaming off a comet interacts with the solar wind, the collisions can produce X‑rays (a process often associated with solar‑wind charge exchange). European Space Agency

Why this matters specifically for an interstellar comet

ESA points out a key advantage: X‑ray observations can be uniquely sensitive to gases that are hard to measure with optical/UV instruments, including molecular hydrogen (H₂) and nitrogen (N₂). That’s important because debates around the first interstellar visitor 1I/‘Oumuamua included ideas involving unusual “exotic ices” such as nitrogen or hydrogen—hypotheses that can’t be tested on ‘Oumuamua anymore because it’s long gone, but can be explored with 3I/ATLAS while it’s still reachable by modern observatories. European Space Agency

ESA also notes that other facilities—such as JWST and NASA’s SPHEREx—have already detected gases like water vapor, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide, and that X‑ray data complements those measurements by widening the menu of detectable species. European Space Agency

Gemini North’s new images show 3I/ATLAS turning greener—here’s what that implies

On the visible‑light side of today’s news cycle, Gemini North (Maunakea, Hawai‘i) imaged 3I/ATLAS on November 26, 2025 using the Gemini Multi‑Object Spectrograph (GMOS)—after the comet reappeared from behind the Sun. Phys.org+1

The images—released today in multiple writeups—show a faint greenish glow around the coma. Phys.org reports that the color comes from gas emission, specifically highlighting diatomic carbon (C₂) as a source of green light, a phenomenon also seen in many “ordinary” Solar System comets when they become active. Phys.org+1

A color change can mean changing chemistry—or changing activity

A subtle but important point in today’s reporting: earlier Gemini imagery showed 3I/ATLAS looking redder, while the new image looks greener, suggesting the comet’s outgassing mix (or relative strengths of emissions) is changing as solar heat works its way into fresh layers of ice and dust. Phys.org+1

Gemini/NOIRLab scientists also flag a familiar comet behavior that keeps observers on alert: thermal lag can cause comets to “respond late” to solar heating, sometimes triggering new emission features or even outbursts after perihelion rather than at perihelion. Phys.org+1

How close will comet 3I/ATLAS get—and is it visible without a telescope?

Let’s translate the “close approach” headlines into practical reality.

Closest approach date: December 19, 2025

NASA’s official FAQ states that on Dec. 19, 2025, 3I/ATLAS will be about 1.8 astronomical units from Earth—around 270 million kilometers (170 million miles)—and emphasizes there is no danger of impact. NASA Science

NASA’s December skywatching guide repeats that it poses no threat and puts the distance in another intuitive comparison: more than 700 times farther than the Moon at closest approach. NASA Science

Will it be visible to the naked eye?

No—today’s mainstream observing guidance is consistent: you’ll need optical aid.

- NASA suggests you’ll likely need a telescope with an aperture of at least ~30 cm for a realistic chance. NASA Science

- El País (English edition) similarly says it won’t be naked‑eye, recommending binoculars or a telescope and emphasizing dark skies; it notes that some observers may see it as a “point of light” with modest optics under good conditions. EL PAÍS English

Where to look (general guidance)

NASA’s “What’s Up” notes that early‑morning skywatchers should look east to northeast in the pre‑dawn hours, with the comet appearing near Regulus (in Leo) around the time of closest approach. NASA Science

El País provides a Europe‑specific example: from mainland Spain, it highlights late night Dec. 18–19 with the comet reaching higher altitude toward morning (local timing will vary by location). EL PAÍS English

Practical tips that match today’s expert advice:

- Prioritize dark skies (rural locations, minimal light pollution). NASA Science+1

- Plan for pre‑dawn observing and give your eyes time to adapt, then use a finder chart or astronomy app to identify Regulus/Leo. NASA Science

- If you have access to a local observatory event, that may be your best shot—both for aperture and for experience. NASA Science

What is 3I/ATLAS, exactly—and why is it scientifically special?

3I/ATLAS is the third confirmed interstellar object ever observed passing through the Solar System—after 1I/‘Oumuamua (2017) and 2I/Borisov (2019). NASA explains that it’s on a hyperbolic trajectory, meaning it’s moving too fast to be bound to the Sun and will not return on a closed orbit. NASA Science

According to NASA:

- Perihelion: around Oct. 30, 2025, at about 1.4 AU (just outside/near Mars’s orbital distance). NASA Science+1

- Speed: about 221,000 km/h at discovery, rising to roughly 246,000 km/h at perihelion (as expected under solar gravity), then decreasing outbound. NASA Science

- Size (still uncertain): Hubble constraints place the nucleus diameter somewhere between roughly 440 meters and 5.6 kilometers (as of NASA’s cited Hubble observations). NASA Science

NASA also notes the comet likely drifted for millions or billions of years between stars before arriving, and that its incoming direction is broadly consistent with the region of Sagittarius on the sky (the direction of the Milky Way’s central region). NASA Science

What it may be made of: CO₂‑rich, nickel signatures—and why X‑rays help

A major thread in today’s reporting is that 3I/ATLAS looks like a comet, but it may not be “typical” in composition.

El País reports researchers have identified large amounts of gas in the coma, particularly carbon dioxide, plus ionized nickel—and quotes astronomers noting that it’s not necessarily that these ingredients never appear in Solar System comets, but that the relative proportions can differ. EL PAÍS English

In the same report, El País also points to:

- jets and dust activity near perihelion (late Oct.), tied to internal heating and volatile release,

- and ALMA‑based work suggesting enriched detections of methanol and hydrogen cyanide in the coma (with explicit cautions that “astrobiology potential” is not the same thing as life). EL PAÍS English

ESA’s XMM‑Newton update adds a complementary angle: because X‑ray observations can help detect gases that are difficult for optical/UV instruments, they can strengthen (or weaken) competing ideas about whether interstellar visitors could contain unusual volatile inventories—especially in hydrogen‑ or nitrogen‑related species. European Space Agency

Hubble (and a fleet of spacecraft) are still tracking 3I/ATLAS—because the window is short

While today’s biggest headline is the X‑ray image, it’s worth noting that 3I/ATLAS is being followed by a broad multi‑mission campaign.

NASA reports that Hubble reobserved 3I/ATLAS on Nov. 30 using Wide Field Camera 3, when the comet was about 286 million kilometers from Earth; the tracking method makes background stars appear as streaks. NASA Science

And NASA’s broader “multiple lenses” campaign describes a truly Solar System‑wide effort—spanning Mars missions, heliophysics spacecraft that can watch near the Sun, and deep‑space probes—because once 3I/ATLAS leaves, it’s gone for good. NASA Science

What happens after December: 3I/ATLAS heads outward toward Jupiter’s orbit

After the December observing window, the comet continues outward. NASA’s campaign summary notes that 3I/ATLAS will pass the orbit of Jupiter in spring 2026 as it exits the Solar System. NASA Science+1

That timeline is why today’s new X‑ray and optical releases matter: they’re part of an all‑hands attempt to extract maximum science—chemistry, dust behavior, outgassing physics, and formation clues—before the interstellar visitor fades beyond reach.