Two days before it reaches its closest point to Earth, interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is giving astronomers and serious backyard skywatchers a rare, time-limited opportunity: observe a visitor that formed around another star, then wandered into our solar system on a one-way trip back to interstellar space.

The flyby itself isn’t close in the everyday sense—NASA says 3I/ATLAS will remain about 1.8 astronomical unitsfrom Earth on Dec. 19, 2025 (roughly 170 million miles / 270 million kilometers, nearly twice the Earth–Sun distance). But for scientists, it’s still “close” enough to run intensive observation campaigns, compare measurements across many telescopes and spacecraft, and test new ways of tracking fast-moving objects. NASA Science+1

What’s new today (Dec. 17, 2025)

Here’s what’s driving today’s coverage and scientific attention around 3I/ATLAS:

- It’s now within two days of closest approach. Space.com reports that as of 12 p.m. ET on Dec. 17, 3I/ATLAS is about 166.9 million miles (268.6 million km) from Earth and still closing. Space

- Fresh observing guides are landing today across major science outlets, emphasizing that this is a telescope target—not a naked-eye spectacle—and pointing readers toward the comet’s current position near Leo and the star Regulus. Smithsonian Magazine+1

- A new research result is reshaping the “weird motion” conversation: a study using interplanetary spacecraft astrometry reports a measurable non-gravitational acceleration consistent with ordinary comet outgassing, tightening uncertainties and producing new mass/radius estimates. Space Weather+2Space Weather+2

- New imaging and multi-wavelength observations are adding color—literally. A Dec. 17 report highlights a greenish glow in recent Gemini North data, linked to changing chemistry in the coma. Universe Today

What is 3I/ATLAS, and why astronomers are treating it like a big deal

3I/ATLAS (also known as comet C/2025 N1) is only the third confirmed interstellar object ever observed passing through our solar system, after 1I/ʻOumuamua (2017) and 2I/Borisov (2019). Unlike comets born in our own solar system, an interstellar object follows a path that’s not gravitationally bound to the Sun—meaning it’s just passing through and will not return. Space+1

The comet was first reported in early July by the NASA-funded ATLAS survey telescope in Río Hurtado, Chile, and researchers quickly recognized from its trajectory that it came from outside the solar system. NASA Science+1

That origin story is why the approaching flyby matters: every measurement—gas composition, dust behavior, how its activity evolves after perihelion—offers a direct comparison to “home-grown” comets, and a clue to how other planetary systems build and store icy bodies.

Closest approach does not mean “close” — NASA says there is no danger to Earth

Public interest tends to spike when the phrase “closest approach” hits headlines. But in this case, “closest” remains very far away.

NASA states plainly that 3I/ATLAS poses no threat, and that on Dec. 19 it will be about 1.8 AU from Earth—around 170 million miles (270 million km) away. NASA Science

NASA also notes that the comet is now heading outbound, moving away from the Sun after perihelion—so the event is observational, not hazardous. NASA Science

“Is it really a comet?” NASA and new data say yes

If you’ve seen speculation online that 3I/ATLAS is something artificial, today’s reporting and the latest science are pushing back hard.

In Space.com’s Dec. 17 live coverage, NASA Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya is quoted emphasizing the straightforward conclusion: “It looks and behaves like a comet, and all evidence points to it being a comet.” Space

What’s fueling some of the chatter is a technical phrase that sounds stranger than it is: non-gravitational acceleration. In comet science, that usually means outgassing—jets of gas and dust streaming off the surface as sunlight warms volatile ices, producing small “rocket-like” pushes that slightly alter motion. NASA’s own FAQ explicitly notes that outgassing can cause small perturbations, and that observations of 3I/ATLAS show these are small and compatible with normal comet behavior. NASA Science

Today’s key science angle: spacecraft data helps measure the “push” more precisely

A notable recent result comes from a Research Notes of the AAS paper circulated via Spaceweather’s hosted PDF. The authors report adding six observations from two interplanetary spacecraft to improve orbit determination and reduce uncertainties on non-gravitational acceleration parameters. Space Weather

Their headline outcomes include:

- A measurable non-gravitational acceleration signal (consistent with cometary activity), with improved formal errors relative to Earth-only data Space Weather

- A rough mass estimate of about 44 million metric tons and an inferred nucleus radius on the order of 260–374 meters (depending on assumed density) Space Weather

Several Dec. 17 explainers are translating that into plain language: the comet’s motion looks “odd” only if you expect it to behave like a perfectly inert rock. For an active comet, small, measurable trajectory nudges are part of the physics. VICE+1

New observations: a green glow, plus X-rays from solar wind interactions

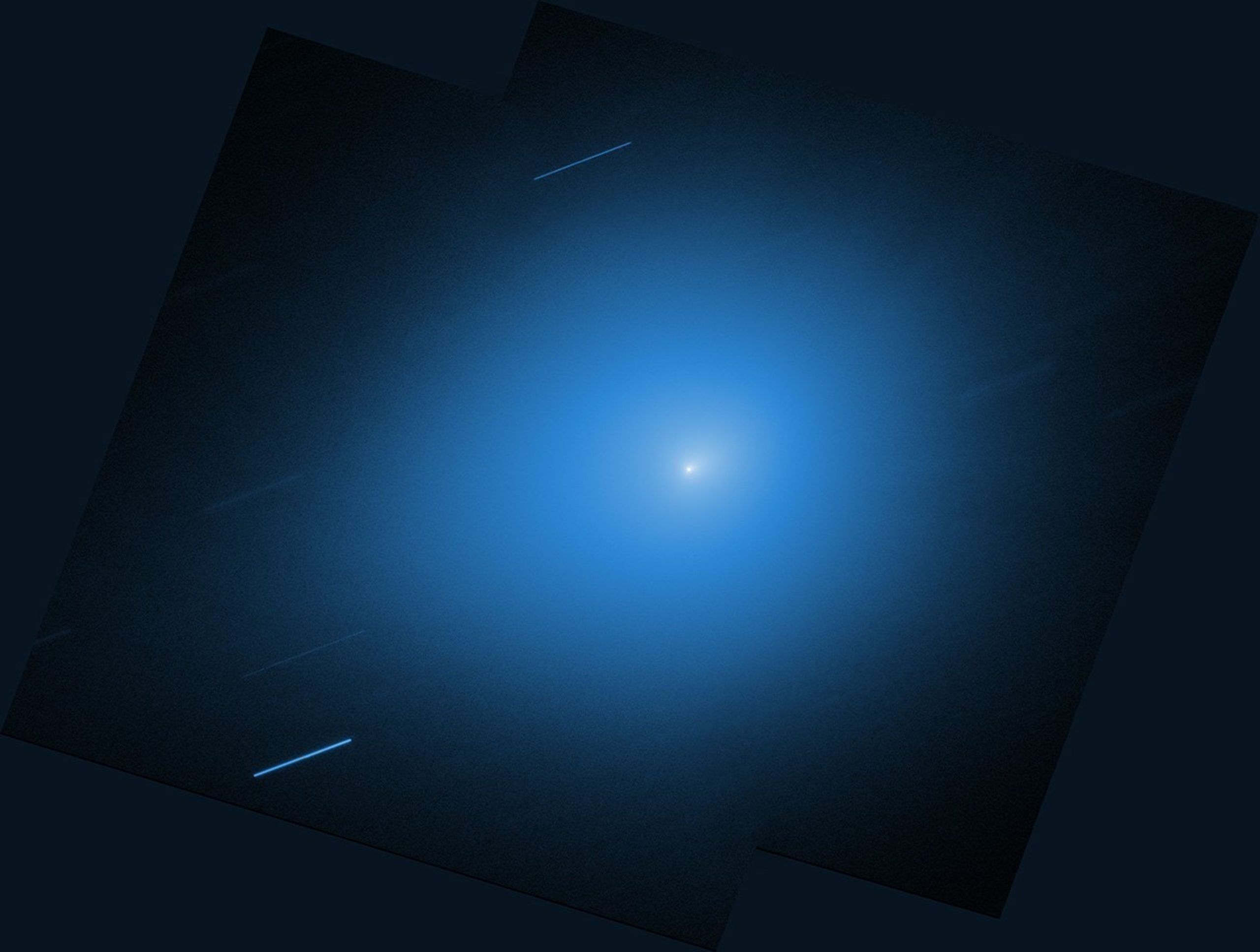

As 3I/ATLAS cools and evolves on its way out, the chemistry of its coma can change—and that can show up as visible color in processed images.

A Dec. 17 Universe Today report highlights new Gemini North observations in which the comet shows a faint green glow, attributed to diatomic carbon (C₂) emitting green light as the comet’s activity changes with heating and time-lag effects in the nucleus. Universe Today

Meanwhile, the comet is also being studied beyond visible light. ESA reports that its X-ray observatory XMM-Newtonobserved 3I/ATLAS on Dec. 3 for about 20 hours, detecting low-energy X-rays produced when gas streaming from the comet collides with the solar wind—an expected, well-understood mechanism in comet science. European Space Agency

NASA’s multi-mission viewing campaign: this is an “all hands” moment

Because interstellar visitors are fleeting, agencies are stacking observations while they can.

NASA has described a broad effort using multiple missions to observe and characterize 3I/ATLAS before it fades and departs for good. NASA Science+1

Some of the most notable spacecraft contributions so far include:

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (HiRISE) imaging the comet in early October during its Mars flyby, alongside ultraviolet imaging from MAVEN and a faint view from Perseverance—data NASA says can help refine size estimates and study released gases, including water vapor. NASA

- Lucy, en route to the Trojan asteroids, capturing images in mid-September that show the coma and tail. NASA Science

- Ongoing support from NASA’s space telescopes, including repeat looks from Hubble (with NASA noting a Nov. 30 re-observation when the comet was about 178 million miles from Earth). NASA Science

How to see comet 3I/ATLAS from Earth on Dec. 18–19

If you’re hoping for a bright holiday comet, this isn’t that. But if you have the right gear—or access to a dark sky and patience—it’s a realistic observing project.

Where to look

Multiple Dec. 17 observing guides converge on the same practical advice: look before sunrise, generally east to northeast, with the comet appearing in the region of Leo and below Regulus (Leo’s brightest star). Smithsonian Magazine+1

What you’ll need

- Not visible to the naked eye (and phone cameras alone won’t cut it). Sky at Night Magazine+1

- Expect it to appear as a faint, fuzzy patch or slightly defocused “star-like” smudge in many amateur setups. Sky at Night Magazine+1

- Space.com notes it will be challenging for small telescopes, with 8-inch-class telescopes under dark skies often cited as a practical threshold for a better chance at detection. Space

If you’re doing it the traditional way (no GoTo/smart telescope), BBC Sky at Night emphasizes careful star-hopping near Regulus—and warns it’s easy to confuse the comet with faint background galaxies in the same region. Sky at Night Magazine

How to watch 3I/ATLAS online

If weather, light pollution, or equipment makes local observing tough, you can still follow the event in real time.

Space.com reports that astrophysicist Gianluca Masi and the Virtual Telescope Project plan a free livestream starting 11 p.m. EST on Dec. 18 (0400 GMT Dec. 19), running through the time of closest approach (weather permitting). Space

Smithsonian Magazine also points readers to the same livestream option as a “stay warm” alternative to predawn observing. Smithsonian Magazine

How fast is 3I/ATLAS moving?

NASA’s FAQ provides clear benchmark numbers that many outlets are quoting today:

- About 137,000 mph (221,000 km/h) when discovered inside Jupiter’s orbit

- Peaking around 153,000 mph (246,000 km/h) at perihelion (its closest point to the Sun)

- Now slowing as it climbs away from the Sun, and expected to leave the solar system at roughly the same speed it entered NASA Science

What happens after Dec. 19?

After Friday’s closest approach to Earth, the comet continues outward.

NASA says spacecraft will keep observing 3I/ATLAS as it heads away, and notes that it will be moving out toward (and then beyond) the region of the giant planets—passing the orbit of Jupiter in spring 2026. NASA Science

AP adds that the comet is expected to pass much closer to Jupiter in March (still a safe, astronomical distance), and quotes NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies director Paul Chodas describing a long departure timeline—eventually disappearing back into interstellar space for good. AP News

Why this flyby matters, even at 1.8 AU

Interstellar objects are a reminder that solar systems don’t evolve in isolation. They shed material—comets, asteroids, fragments—that can drift for millions or billions of years before briefly crossing another star’s path.

And while 3I/ATLAS won’t be a naked-eye showpiece, it’s turning into something arguably more valuable: a well-observed, multi-wavelength, multi-spacecraft case study. Between updated orbit solutions, chemical clues from changing coma emissions, and cross-checked measurements from Earth and deep space, the December 2025 campaign is building a detailed “exit interview” with a visitor we’ll never see again. NASA Science+2Universe Today+2